Some folks are still bitching that the Eternal Mardi Gras is a Disney version, what with the traditional Krewes’ parading limited to the traditional lead-up to Fat Tues-

Some folks are still bitching that the Eternal Mardi Gras is a Disney version, what with the traditional Krewes’ parading limited to the traditional lead-up to Fat Tues-

day while the big budget corporate floats from Hollywood, Bollywood, and Pornywood parade all year, all long, all over New Orleans, which is sort of true, given that it was Disney I brought in first.

But whining that the Mouse has gone and done to the French Quarter what it did to Times Square, and oozed out into the rest of New Orleans like the annual dose of mud dur- ing the Hurricane Season, and calling yours truly, Jean-Baptiste Lafitte, a swamp rat traitor to the true soul of the city is going a tad too far, seeing as how the Quarter had fallen far off its fabled glory days even before Katrina.

You expect me to apologize for saving the city from drown- ing to death?

Oh yes, I did!

Everyone knows New Orleans had been on its economic ass for decades, barely able to pay the cops to keep the Swamp Alligators down in their lowlands swamps and out of the New Orleans Proper high grounds.

And the Hurricane Season wasn’t going away, now was it, and what the Dutch were demanding in order to save what was left of the Big Easy from finally going under would’ve been about the total budget of the city government for the next decade or two. No high-priced, high-tech Hans Brinker sea- walls and solar windmill pumping stations back then, need I remind you?

I guess I do.

Amazing what short memories ingrates have.

New Orleans featured itself as the Big Easy since before Mickey Mouse was even a gleam in Uncle Walt’s evil eye, but just because the truth wouldn’t look so good in the tourist guides doesn’t mean we don’t all know that it’s always really been the Big Sleazy, now does it?

This city was making its living as a haven for pirates and slavers and the riverboat gamblers, saloon keepers and whore- house impresarios like yours more or less truly, rollers high, low, and medium, who serviced their trade since before the Louisiana Purchase.

The Big Easy was born as the Big Sleazy. Easy?

Yeah, sure.

Born between a bend in the mighty and mighty ornery Mis- sissip and a briny marsh presumed to call itself Lake Pontchar- train serving as an overflowing catch-basin for tidal surges when the major hurricanes hit and a giant mud puddle in- between.

Easy?

First built precariously on the natural levees of the Missis- sippi, expanding greedily and stupidly into the back swamps. Tossed around like a beachball between the French and the Spanish. Finally sold to the Americans by Napoleon on the cheap because he knows he’s gonna lose it to the British anyway if he doesn’t. Flooded every few decades even before Katrina, before there even was an annual Hurricane Season, squeez- ing what remained onto what high ground was left to it after the sea level rose. The population cut almost in half, forced to live off the tourist and entertainment trade alone when the Gulf oil dried up, just about surrounded by the Alligator Swamp and what crawled up out of it if its back was turned.

You call that Easy?

Those who adapt survive, like the Cajuns from icy Quebec said when they found themselves in the steamin’ bayous of the Delta, like the Alligator Swamp nutria hunters turning a plague into protein. Those who don’t ain’t been heard from lately. So making legal what the Big Easy always was to pull our termi- nal condition from the mud is not “selling out the soul of the city” or “whoring ourselves to the mavens of show business.” Because the Big Easy has always been a whore, a charming, sleazy, free-wheeling, good-natured hooker with a heart of gold and an eye for the main chance, which is what makes her easy, and bein’ easy is the name of the game in this business, which has always been the main game in town. And let an old bor- dello impresario tell you, who would ever hire a hooker who

wasn’t all of the above, and good-lookin’ too?

In case you’re forgetting, the Big Easy wasn’t exactly look- ing as appetizing as a platter of Oysters Bienville back in the day before Mama Legba and Her Supernatural Krewe. She’s all spiffed up and lit up and giving herself the star treatment now, to the point where ingrates and ignoramuses and Creole romantics looking back over their shoulders can afford to complain about how New Orleans is peddling her previously jazzy derrière to less than the genteel bohemian trade of their absinthe fantasies.

Whoever wrote that song about there being no business like show business sure got it wrong. As things stand now, there’s no business but show business and we all are in it. Not that we haven’t always been. The only difference now is that it’s making the good times roll again after all those years in the deep dark shit, and that’s good enough for me, and if it’s not good enough for you, this ain’t your town, you’d best leave and go somewhere more to your tight-assholed liking.

But y’all come back on vacation from the salt mines, y’hear! Whatever your pleasure, we got it, and if we don’t, don’t worry, no matter how pervo it may seem to your sweaty ves- tigial morality, we’ll get it for you. Here in the Eternal Mardi Gras of the Big Easy, we make no such judgments, we’re im- possible to scandalize, de gustibus non est disputandum.

What pays here, stays here, and never fear, we do still want your money.

2

Patrolman Luke Martin had “enforced” more final evic- tion warrants than he could count or cared to, and while it didn’t exactly make you feel like a hero kickin’

folks out of their houses and into the street, it was far from the worst duty, sure better than dealing with pickpockets and muggers from the Alligator Swamp trying to work the Quar- ter or gangbanger patrol duty guarding the swamp itself.

There had been a few minor firefights when this dirty work got dumped on the New Orleans Police Department, but these days you did it with a partner, and the two of you were issued military body armor and M35s hung with enough scopes and grenade launchers and fancy doodads to scare the shit out of the civilians in question to the point where no cop he had ever heard of had ever needed to fire one of the things even when the former homeowner was armed with a sawed-off shotgun or a rusty M16. Sweet duty in a way, ’long as you didn’t think too hard about it.

But—

“Is this some kind of fuckin’ joke?” were the first words out of his mouth when he read the address and the name on the latest final eviction warrant handed to him.

“You find something fuckin’ funny about one more poor sucker’s eviction notice?” snarled Sergeant Larrabee, aka Sergeant Slaughter, aka the Mouth That Roars. “You’re not some kind of sicko Bourbon Street comedian, Martin, you’re a cop, remember, or anyway you’re dressed like one and this ain’t Mardi Gras, so keep your black sense of humor to yourself, just take Moreau with you, hold your nose, and go enforce it.” There it was, the full legal form of his name on the final eviction notice, the exact same form on the mortgage contract he had so proudly and hopefully and stupidly signed less than two years before the onset of the Great Deflation, aka the Steroid Dollar, aka the Superbuck, aka Up Shit Creek.

“Don’t you read these fuckin’ things before you hand them out?”

“Read them? You out of what passes for your mind, Martin? Don’t you know how many of them come down across my desk every fuckin’ day? Of course you do, Martin, you must’ve enforced at least a hundred of ’em by now yourself.”

“This is my house,” said Martin Luther Martin.

“Say what?” grunted Sergeant Larrabee, snatching the poi- son paper out of Luke’s hands. “Jesus H. Christ on an air- boat!” he sort of moaned when he took a good look, in a tone of voice that made him sound almost human. “Martin Luther Martin!”

Almost. For a moment.

“Martin . . . Luther . . . Martin? Now where did an ol’ ga- tor like you get such a highfalutin handle? Yo daddy had himself a reefer dream?”

What Daddy had as far as Luke could remember was a bad smart-ass attitude. Martin Luther Martin had always loathed the official name inflicted on him at birth, and hearing it out of Larrabee’s flannel mouth, let alone seeing it on this piece- of-shit paper sure didn’t make him like it any better.

He was calling himself Luther about the time he learned to talk, transmuting it into Luke as his gangbanger tag in the Vu Du Daddies, cool hand that he styled himself after seeing the Paul Newman movie on an ancient TV they had snatched, no Mohammed This or Barack That bullshit for him, no Rat Man or Baron Saturday or other such Vu Du mumbo jumbo either.

So Luke Martin was a self-made man from the git-go, who had a choice, Papa doin’ long hard time in Angola for general bad-ass thuggery by the time he hit the first grade in what passed for school, Mama makin’ her junkie ends meet by selling the shit and her pootie at street level, that is, to the ex- tent that you could call anything a street in the Alligator Swamp.

Mudville, Stilt City, the Alligator Swamp, whatever. Mudville because the so-called streets were unpaved path-

ways of mucky mud when they weren’t underwater. Stilt City because anything that wasn’t built up on a platform tall enough to keep it above the incoming surges during the Hur- ricane Season wasn’t going to be there for very long.

The Swamp because it was what had been called the “back swamp” way back in the day before the young city called New Orleans started slithering down off the natural levees of the Mississippi and the Esplanade and Gentilly Ridge and such- like into the sea-level lowlands and worse. And the poor- est of the poor had been living there even then, squeezed between the levees and ridges and the real bayou swamp- land between the spreading city and the Gulf of Mexico, more or less, and sometimes much less, absorbing the tidal surges and keeping it from being flooded with salt water.

These days, what with the rising sea level, and the various canals stupidly dug down through the decades to connect the old natural harbor to Lake Ponchartrain and to the Gulf, the far back-swamp bayou land was now under salt water, and the more or less habitable front of the back swamp that wasn’t, except during the Hurricane Season when it too was more or less under water, had moved inland all around what high ground remained.

So no one tried to build anything that wasn’t stilted and platformed above the record high-water mark or if they were stupid enough to try it, got drowned out within a year, and during the Season, New Orleans Proper—as the proper folks living there had taken to calling it—was more or less surrounded by a cross between a Third World version of a country-mouse Venice and the long-gone true bayou country of zydeco-mourned forlorn Cajun lore.

Mostly wooden stilt-huts on mostly wooden platforms mostly clustered together in mostly self-contained villages like something carved out of clearings in the Amazon rain forest or on the low-lying shores of the Mekong Delta. One-room grade-school buildings in the bigger ones that the law still more or less required the city to provide. Outdoor markets selling swamp-grown vegetables, swamp-hunted nutria meat, swamp- caught fish, crab, shellfish, and crawdads. Liquor stores, cloth- ing huts, and general stores selling most everything else, mostly tools, fishing gear, guns, ammunition, and more of them than not serving as fences for stolen goods.

During the relatively dry seasons, it was foot traffic on the muddy village streets, and not much better from village to village, and during the wetter days, which were about half the year, it was patched-up rubber zodiacs, homemade lightweight and shallow draft canoes and kayaks, and half-assed rafts pre- tending to be gondolas.

As America thought of itself, as New Orleans Proper thought of it, the Alligator Swamp might be a shameful rural slum that belonged somewhere in the deep Third World Boonies, but as a Third World Boonie, it was better than most.

Enough growing months when it wasn’t Hurricane Season and enough rich-soiled farmland to grow just about any veg- etable, if nothing that grew on a tree or grew like a grain. Back away into the new bayou back swamps, there was abundant saltwater seafood fishing and trapping. The uncounted hun- dreds of thousands or even millions of nutria—amphibious rodents the size of beavers that banged like bunnies and reproduced like rats—that had once been a despised plague destroying the freshwater swamp vegetation had been driven closer in by the salting of their previous turf, right under the village huts during the Hurricane Season, and were now an abundant supply of easily hunted meat. Easy small-plot farm- ing. Easy fishing and lazy-man’s hunting.

A subsistence-level lifestyle, maybe, but a good one, almost a paradise if you were into it.

The Alligator Swamp not because the real reptilian deal had indeed managed to make its way up from the bayous but because it was a shithole if you weren’t a teenage human al- ligator hungrily clacking your teeth at what you knew all too well was up there that you couldn’t have in New Orleans Proper, as the mofos there called it.

The French Quarter, with its saloons, and bars, and music halls, and high life, the Business District and Magazine with their supposedly easy pickin’s, and the burglar’s dream Garden District hovering there on the high ground like the literal City on the Hill, had much more appeal to the boys in the hood than a lifetime of dirt-farming in the mud or hunting swamp rats or fishing for your food.

But knowing full well that their chances of honest gainful employ in New Orleans Proper were slim and none, the boys trying to become men, and the men who didn’t know how to stop being boys and really didn’t want to, became the top pred- ators of this ecological niche, sharp-toothed and lizard-hearted young Alligators who would bring down their own fathers if they could find them and devour their own mothers if the bitches ever accumulated anything worth stealing.

For a teenage Alligator, the down-and-dirty economic base of the Swamp was low-level drug dealing and pocket-picking and drunk-rolling and such in the Quarter or the Magazine District one step ahead of the police if you had the brass balls to try it, but mainly joining one of the gangs preying on the softer targets in your own hood.

So young Luke took the path of least resistance, not that the resistance was insignificant, not that there was any other path to take, and managed to gain admission to a scruffy and scurvy low-level gang called itself the Vu Du Daddies, though what they knew or cared about voodoo would fill about five of their remaining brain cells, and as far as they were concerned what they might father by gangbanging some skank was none of their business.

What was their business was what more powerful Alligator gangs allowed to be their business, which wasn’t very much. Muggings. Burglaries, but not of the more lucrative liquor stores, which were reserved for the dominant gangs—more like bottom-of-the-food-chain dealing.

Of course, you could always get a job and leave. That’s what they told you in school if and when you bothered to show up.

Hah, hah, hah.

There weren’t really enough “proper” jobs in “proper” New Orleans to keep much more than half of its “proper” populace above the official poverty line and their heads, uh, above water, so no one up there with a job on offer was about to lay it on something that slithered up out of the Swamp.

But one not so fine day not that long after the Hurricane Season, Luke emerged from the family hut toward sundown to join the Vu Du Daddies for a night of nothing in particular and had a vision that changed his life.

The streets were in the slow oozy process of emerging from the floodwaters, the worst time of the year for getting around, with the so-called village streets no longer flooded but up over your ankles in mud, and what was left of the waterways so shallow that proceeding by canoe or raft was like mud pup- pies flipflopping their way from puddle to puddle.

Nevertheless, or maybe because their meth-sotted brains saw this as some kind of advantage, a half dozen members of the Fuck Yo Mothers had boosted some out-of-date TVs and computers from somewhere and were fleeing with the loot in two wormy old bayou pirogues fitted with rusty electric out- boards, here and there having to dismount, hold tight to the gunwales, and, cursing and bitching, push their overladen boats off a not-yet emergent mud bank.

The Fuck Yo Mothers were as high up the food chain as it got in the Swamp, which only made this sorry spectacle even more pathetic, and Luke might even have laughed at these addled buffoons were it not worth your life to be caught doing so.

And then Luke heard a rock and rollin’ thunder like a low- riding helicopter gunship, and ’round a bend it came at about fifty miles an hour, with an actual airplane propeller whirling and roaring inside a wire cage behind some kind of racing car engine, planing a flat-bottomed boat like a huge water ski magically slip-sliding over mud and water alike and leaning over into the turn like a motorcycle—one of those high-speed airboats snapped up at cut-rate prices by the New Orleans Police when the Okefenokee and the Everglades became deep year-round lakes, kicking up a rooster-tail of mud and water behind it, and pushing a heady cloud of expensive gasoline fumes before it. Whoo-ee! Enough to give a teenage Alligator a hard-on for hot iron, and it more or less did, and likewise in spades for the three cops riding it and having a high old time, at least as Luke was seeing it: one driving the speeding airboat, another standing up beside him waving a pistol, the third at some kind of long-snouted curdler mounted on a swiveling pedestal.

The police airboat caught up with the Fuck Yo Mothers in nothing flat, and took to gliding mocking circles around their two boats, then neato figure eights around and between them just to taunt them, hah, hah, hah, go fuck yoselves, muthas!

Now, of course, anything in the Swamp with descended tes- ticles automatically hated the cops, Luke being no exception, but who could keep from laughing at this sarcastic display of police primacy at the expense of and over these feared lizard- lords of the Alligator Swamp?

And that was when it came to him, even before the cops began playing the tight beam of their sonic curdler over the Fuck Yo Mothers, causing them to scream, grab at their ears, and, it would seem, piss, and possibly shit in their pants.

Think of the Cops as just another gang and it was immedi- ately apparent.

The Cops were the Supreme Gang of the Alligator Swamp.

They had the top gear. They had the colors. Each of them got a top-of-the-line gun for nothing and plenty of ammo for it. Each of them made more money in a year than anyone else in the Swamp, without risking hard time in Angola like Papa.

Forget the Vu Du Daddies, Luke told himself. Forget trying to join the Fuck Yo Mothers or the Spades of Ace or the Darth Invaders.

The Police is the gang to get into.

That was when Luke knew that a Cop was what he wanted to be, had to be, and he never looked back. The Police were always looking to recruit a few gang members from the Alligator Swamp for their down-and-dirty knowledge, but rarely getting any takers, seeing as how they were the Enemy, not to mention that you couldn’t even try to get into the police acad- emy without being a high-school graduate.

But if you looked at the Cops as just another gang, as the toughest, best-armed, best-equipped, richest gang of all, you took advantage of the invitation to try your stuff at the police academy.

Bummer that it was, Luke actually started going to the lo- cal one-room school regularly enough and studied just hard enough to get into Brad Pitt High School, a long, hard, and somewhat dangerous daily commute from his own hood in the southeast edge of the Lower Ninth Ward through some- times hostile territory by a ratty kayak he stole and defended with a rusty Bowie knife by waterway when he could, slog- ging through the mud when he couldn’t, and squeezing through to a high-school diploma.

After all, looked at the right way, it was better than having to make your bones, or get banged by the whole gang, or go through some disgusting punk vu du ceremony, which was the sort of thing you had to do to join any other gang worth get- ting into.

3

et me tell you, New Orleans was knocked back on its soggy ass by Katrina, and much worse by the advent of the Hurricane Season, and so was I. Katrina was

nothing compared to what followed, like a pug got knocked down in the first round by a haymaker, managed to crawl more or less to his feet on the eight count, only to get socked again, and again, and again, each roundhouse right stronger and stronger.

Before Katrina, ol’ J. B. was riding high on the return from three saloons, one of which was actually in the Quarter, and a couple of cathouses, one of which was a fancy three-story establishment in the Garden District. None of ’em was washed away by Katrina, and all of them were high enough to survive even the annual Hurricane Seasons.

But the same could not be said for the tourist trade, knocked back down after it had just about recovered from Katrina by one Category 3 or 4 storm after another during what came to be called the Hurricane Season, by at least one Category 5 hurricane a year, by the rising seawater of the Gulf surging up through the waterways and canals and down over the banks of Lake Pontchartrain, squeezing what was left of the Easy part of the Big Easy up onto the levees and ridges.

It finally got through to the powers that be at the time, or anyway to Cool Charlie Conklin who was then the mayor and well known for knowing which side of his bread the butter was on, that this situation was going to be permanent, and the only way to save the city from completely turning into a se- ries of islands in the watery muck was to draw borders around what could afford to be saved by permanent pumping opera- tions and internal levees, and giving up on trying to save the rest of the city by letting nature do its stuff and turn it back into the buffering marshland that had once been known as the back swamp.

Charlie Conklin also knew where the votes weren’t, which was in the lowlands first depopulated by Katrina, and turned into isolated faux Third World villages by the Hurricane Sea- son, inhabited by fragmented tribes of blacks who had been there for generations, Cajun refugees from the bayou country now permanently under water, Vietnamese fish-folk, and the like, the sort of population highly unlikely to get it together to vote as a constituency, so he was able to get away with this bottom-line political calculation.

Which was cool, if you were among the electorate up on the Quarter, or Metarie, or the Business District, or the Garden District and so forth. What was not cool if you were in the saloon and bordello trade was creating an urban bayou land known all too far and wide thanks to the less-than-favorable media coverage as the “Alligator Swamp,” legendarily infested with human reptile life whose gangbangers slithered out of it of it whenever they could to seek their pickings in the turf of honest sleazy impresarios like me.

So in practice the tourist district, aka the Zone, was more or less reduced to the areas bordered by the Mississippi and Canal Street, and maybe as far north as Rampart or maybe Claiborne, and as far east as Esplanade or maybe Frenchmen. And after a passel of nationally and internationally colorfully reported unfortunate incidents, it sort of became official via hotel and tourist board pamphlets and maps, and by the con- centration of the majority of police patrols and sometime checkpoints guarding its periphery.

Well, as you might imagine, the two saloons whose prem- ises I rented outside the Zone became the giant sucking sounds of expenses over receipts gurgling down the drain. I owned the building the one in the Quarter was in, or thought I more or less did because I had twenty-three years left on a fixed-rate mortgage I could easy afford thanks to a federal loan shark subsidy I didn’t really understand or want to, or so I thought at the time. It ran at a small profit, and I had a nice apartment with a balcony above the bar.

The bordello in the Garden District was further in the black, and I owned that too along with your friendly government subsidized and regulated mortgage packager, but the whore- house outside the Zone became a den of meth and heroin- addicted hookers half a step up from street traffic, and what they attracted is something you don’t want to think about, and neither did I.

Those who adapt survive, so I closed everything that I was renting space for, leaving me with the nameless bordello house known only by its address and phone number, and my Bourbon Street saloon, Lafitte’s Landing, and a much-reduced monthly nut to carry.

If it was no longer exactly cocaine and cognac and An- toine’s for lunch and dinner every day, at least it was only a few cuts below the lifestyle to which I looked back so fondly to have become accustomed to.

No one expects the Spanish Inquisition or the Banking Crash of ’08 or one disastrous hurricane to be followed by an endless line of bigger and bigger brothers and sisters or an alligator to come up through the toilet and bite you on the ass.

So how was I to foresee the Great Deflation Scam?

How was anyone except the sons of bitches who ran it, whoever they really were?

And there is smart or not-so-smart money claiming that, in the end, they really didn’t even know what they were doing either.

4

With a diploma from Brad Pitt, Luke found getting into the Police Academy mysteriously easy and when he found out how right he was about the

Cops being the top gang in the Alligator Swamp, he found out the reason why.

The tourist street crowd life in the Zone being such a big slice of the economy, the police force had always been under- manned in venues not involved in the tourist trade when it came to keeping the peace in poor and mainly black neighbor- hoods like the Ninth Ward or northeast Tremé.

Post–Hurricane Season, with where the money was to be made more or less surrounded by the Alligator Swamp, the most important job of the NOPD was to keep the Alligators down there where they belonged and, above all, from invad- ing the Zone.

Completely cordoning it off would have required a police force far larger than anything the city government could af- ford, so the only viable tactic was to make the gangbangers live in fear of the cops, and the only place to do it was inside the Swamp itself.

This had long been accomplished by arbitrary airboat patrols, arbitrary billy clubs laid upside arbitrary heads, the occasional terminal elimination of gang leaders who got too big for their britches, and other assorted acts of forthright po- lice brutality, busting such would-be perps and treating them to prolonged free food and shelter in jail cells being counter- productive to the municipal budget.

But now some asshole in the mayor’s office had persuaded Sam Bermudez to set up a so-called Experimental Community Outreach Unit in the Lower Ninth, and recruit a few Alliga- tors from the Swamp itself to partially man it.

So soon as he had the badge Luke found himself dropped right back into the Alligator Swamp, into the Lower Ninth Ward, into one of the crummiest of the Brad Pitt Houses con- verted into what was laughingly called a new district police station.

The Brad Pitt Houses were originally a noble development godfathered by an idealistic movie star close up to the sec- tion of the Industrial Canal levee breached during Katrina, something like a hundred single-family homes made available with all kinds of subsidies to those who had lost theirs in the flood.

Pitt had commissioned world-class architects to do their stuff, the main rules being that the houses had to be built up on stilts or pylons to survive the further flooding, which the advent of the Hurricane Season turned out to supply in abun- dance, and have energy-wise solar panel roofing. Most of the results were artistically stunning, but the new Ninth Ward Community Police Station was not one of them.

One of the earliest built, it resembled an outsized aluminum shipping container propped up on metal piping of the sort used to frame staircases in parking garages. It was also out- side the electrified fence of what was now a gated community besieged by the Alligator Swamp and the lowlife wildlife within to which it was an all-too-tempting target.

The ward room of this dump was where Luke Martin found himself dropped along with the other eleven cops who consti- tuted the new unit to be greeted by a lieutenant whose orders were delivered in jaundiced terms that were brutally clear.

“The New Orleans Police Department does not have the men or the money to adequately protect this place from what periodically tries to short out the fencing for the purpose of sacking it, but the Brad Pitt Houses are a political sacred cow, and if that were to happen, there would be holy hell to pay at City Hall, and as y’all might be aware, shit flows downhill, meaning from the mayor to the police commissioner, and from there to you. So your mission is to keep that from hap- pening and nobody gives a fuck about how. Just make it so and don’t bother filing reports. Screw up and nobody ever heard of you.”

So saying, higher authority departed, leaving the Experi- mental Community Outreach Unit all on its own. You didn’t exactly have to be a political sophisticate to figure out that no one in the police department had a clue as to how it might accomplish its mission, and that the higher-ups probably be- lieved it was impossible and really didn’t give a shit if it failed because its very existence was some sort of political ass- covering operation and nothing more.

Twelve cops in a unit supposedly ordered to pacify the im- mediate area besieging the Brad Pitt Houses or maybe even the whole fucking Lower Ninth—yeah, sure. Three veteran cops a few years from retirement, and probably assigned to the unit as a garbage dump, seeing as how the three of them were overweight and out of shape drunks, and Sergeant Rick Harrison, who had no idea of what orders to issue beyond “Bring that bottle over here.”

The eight other cops in the unit were, like Luke, recruits from the Alligator Swamp straight out of the academy, unable to get into a Swamp gang of significance and hoping they could be better positioned to line their pockets under the colors of the Police.

Only Luke took the mission seriously and only because no one else did and it therefore afforded him the first oppor- tunity he had ever had to become a gang leader himself.

He set up a firing range close by the gate to the electrified fence and easily enough persuaded his fellow Alligators to blast away. He organized mass nutria hunts in the surround- ing swamp and left piles of the dead rodents around to rot as calling cards. His Alligator squad took to doing likewise with the real-deal reptiles, chopping off the heads and impaling them on poles as exclamation points.

To his gang of Alligator Swamp Cops, this was just good dirty fun, but Luke had a point to make, that there was a new gang on this turf, namely the Alligator Swamp Cops, and they were trigger-happy badasses not to be fucked with and out to rule.

Toward this end, he took advantage of a half-assed attempt by some local gangbangers to breach the electrified fence to bullshit Sergeant Harrison into bullshitting the higher-ups into supplying heavier weaponry, hoping for an airboat, which was not forthcoming. But they were issued M35s, stun grenades, two handheld sonic curdlers, a couple of crates of tear gas grenades, gas masks, riot shields, and electric billies.

Fully dressed in these colors, the Alligator Swamp Cops trudged and canoed around the swampland, blowing away nutria and alligators in the process of showing the flag, violat- ing the turf of the local gangs with swaggering impunity, and all but calling them pussies and daring them to come out and fight.

Luke didn’t really expect them be stupid enough to offer themselves up as target practice for this level of ordnance. He expected them to bitch about it sooner or later one way or another and waited for it to happen. It finally did in the form of Ally X, honcho of the Fuck Yo Mothers, the acknowledged top gators in this neck of the Swamp, who swaggered into the police station decked out in twenty pounds of cheap steel bling and piercings, packing a pair of rusty revolvers, and doing his best not to look nervous as he shouted at Sergeant Harrison, who was in the process of washing down a shot of bourbon with the last of a six-pack of beers.

“Yo mo, bobo, what the fofo goin’ on?”

Harrison shouted for Luke, who had long been waiting for something like this, had watched Ally X enter the building, and had assembled his posse just outside.

“Get yo ass out here, you wanna know what the fofo goin’ on, mofo,” Luke shouted back.

When Ally X did, he found himself surrounded by a semi- circle of fully armed and armored Alligator Swamp Cops and backed up uncomfortably close to the electrified fence.

“I’m gonna tell ya, mofo, and you gonna tell yo’ bobos, and y’all gonna spread the word from the bird fuck’ far an’ fuckin’ wide—”

“Wish is—”

“Wish is there’s new colors inna Swamp, an’ you lookin’ at ’em, and the name of our gang is the Alligator Swamp Po-lice, and the deal is we rule. We the top of the food chain in this here turf, and we do not take shit, an’ shit is what we will get from what’s up the food chain from us if they get the idea we not doin’our job. And our job is to tell you how to do your job, so here’s how it is. . . .”

Luke’s Alligator Swamp Cops flipped their M35s down into firing position and pointed them at Ally X before he could do more with his mouth than drop his jaw wide open, and Luke laid it out:

“Look, the po-lice don’t want no trouble and trouble for us is getting shit from upstairs because you motherfuckers are making trouble down here, like any you mofos get so much as in sight of the Brad Pitt Houses, like any you mofos try to cross the canal into the Zone, like any you mofos fuck with anyone but other mofos down here—”

“Oh, yeah, bobo?”

“Cor-rect, mofo. These are the rules now, we find you dis- obeying them, we come after y’all and we do not stop till we got no more targets.”

“Well, what the fuck does that leave us to do, mofo? Chase fuckin’ nutria an’ pray t’Jesus?”

“Look, my man, the police don’t want no trouble from what goes on in the Swamp as long as it stays in the Swamp and don’t make any trouble for us—”

“Meanin’ what?” Ally X demanded belligerently. But Luke could smell it was turning phony, turning into a necessary face-saving show.

“Meaning don’t make trouble for us and we won’t make trouble for you. We not gonna be runnin’ no hos, we’re not gonna deal no stuff, an’ if we steal this and that once in a while, it’s just gonna be for personal use. Meaning the police are not here to be bad for business. Who goes along, gets along . . . ain’t there enough shit in this city already? We don’t have to make no more for each other, now do we?”

Copyright © 2017 by Norman Spinrad.

~~~

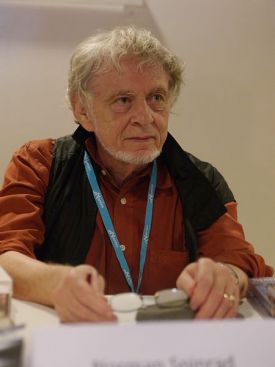

Norman Richard Spinradis an American science fiction author, essayist, and critic. His fiction has won the Prix Apollo and been nominated for numerous awards, including the Hugo Award and multiple Nebula Awards.

Norman Richard Spinradis an American science fiction author, essayist, and critic. His fiction has won the Prix Apollo and been nominated for numerous awards, including the Hugo Award and multiple Nebula Awards.

Born in New York City, Spinrad is a graduate of the Bronx High School of Science. In 1957 he entered City College of New York and graduated in 1961 with a Bachelor of Science degree as a pre-law major. He has lived in San Francisco, Los Angeles, London, Paris, and New York City. Spinrad served as President of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) from 1980 to 1982 and again from 2001 to 2002. He has also worked as a radio phone show host, a vocal artist, a literary agent, and President of World SF. (wikipedia)

Norman Spinrad can be found on Facebook and on his website.

And you can participate in agitating for a Grandmaster award for Spinrad as well. Read this

For a bit of historical background on the author, here are scans of the interview conducted by Joseph Zitt for our fanzine – CONTACT:SF.

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.