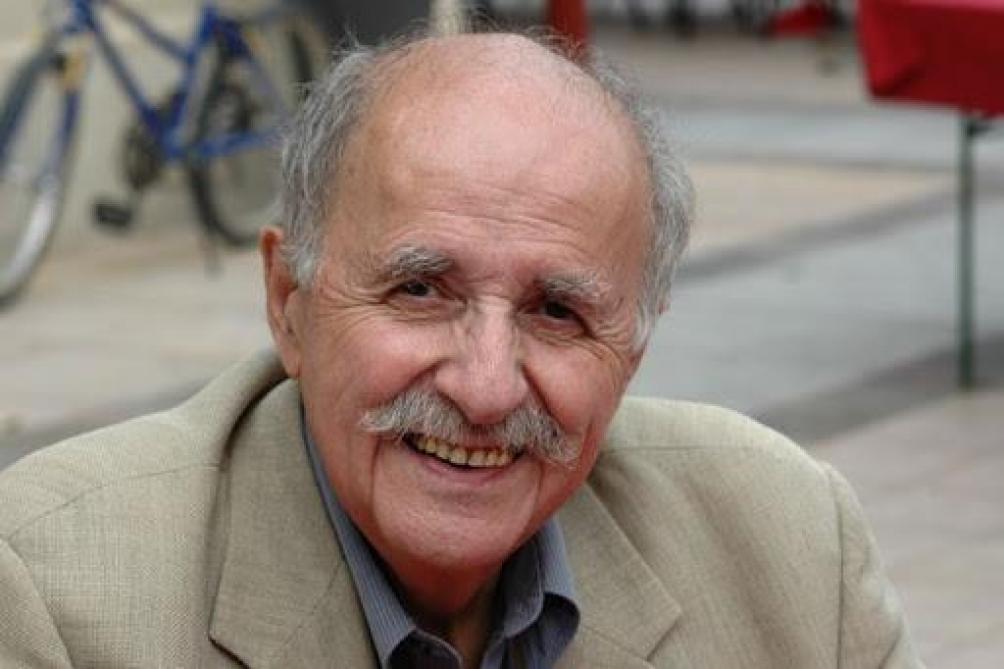

From Smart Pop books comes the “completely unauthorized” Boarding the Enterprise – Transporters, Tribbles and the Vulcan Death Grip in Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek, edited by original Trek fan boy David Gerrold and his unabashedly lover-of-all-things-Trek cross-border counterpart Robert J. Sawyer.

From Smart Pop books comes the “completely unauthorized” Boarding the Enterprise – Transporters, Tribbles and the Vulcan Death Grip in Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek, edited by original Trek fan boy David Gerrold and his unabashedly lover-of-all-things-Trek cross-border counterpart Robert J. Sawyer.

What a pleasure it is to talk about a book that has been put together by two authors whose work you are A: familiar with (intimately in some cases) and B: like.

That last qualifier is important, because if I didn’t like their fiction work, it is doubtful that I’d bother spending time on some non-fiction filler product probably put together for no other reason than to help make another car or mortgage payment.

I’d also not know as much as I do about the editors (who bothers to learn anything about authors whose work they don’t like?), both of whom I’ve met with and corresponded with over the years (and – plug: one of whom I’ve had the pleasure of working with – see A Doctor for the Enterprise), which, in both of their cases means that I know both of them are Trufans. Which lends reading anything they have worked on an added spark; not only do they produce this stuff – they MEAN it.

Which means that Boarding the Enterprise is anything but a filler. It’s a love letter in multiple essay form form two dyed-in-the-wool Trekkies*, who’ve gathered together a handful of other authors who share both love and history with that most iconic of all SF television shows, Star Trek.

The little bit I know about David Gerrold includes the fact that like all fans, he enjoys word play and, in particular, puns that will make listeners groan. I suspect that this book’s title is one such: “boarding a show” may reference storyboards, or stage boards or some other inside TV speak, so it seems that even before flipping the cover, we’re in for a typical Gerrold experience – fun, yet pointed.

Sawyer is “an original series die hard”. He owns a 33 inch model of the Enterprise. He can call out individual episodes of the other series by name. ‘Nuff said.

(For Trekkies, I can’t imagine anything more fun than getting to watch these two talk about Trek. Which they apparently have on, of all places, Facebook.)

BenBella (Smart Pop) released Boarding in 2006 on the occasion of STar Trek: TOS’s 40th anniversary. It is a fitting homage.

Contained within its pages are essays on the experience of working on Star Trek and musings on the meaning of Star Trek, not to mention forays into the legacy of Star Trek.

The contributors cover the gamut: David Gerrold and Robert Sawyer, Norman Spinrad (The Doomsday Machine), D.C. Fontana (numerous episodes), Allen Steele, Eric Green, Michael A. Burstein (an occasional contributor here and – special note: the short film based on his story I Remember the Future is eligible for a Hugo Award in 2016 by special dispensation), Lyle Zynda, Don DeBrandt, Lawrence Watt-Evans, Robert A. Metzger, David DeGraff, Adam Roberts, Melissa Dickinson, Paul Levinson and Howard Weinstein – SF authors, fans and lovers of Trek (if not writers of Trek) all.

Gerrold’s essay stands out for me because David seems to be intimately familiar with the history of our genre and he ties Star Trek’s origination into it in a meaningful way; he mentions Trek’s intimate history – the advent of color television, the need to compete with another network’s show (Lost In Space), the influence of ratings and how a time shift during syndication introduced the show to a whole new audience who would make it the phenom it became. And then he recounts the other half of the show’s history thusly:

Way back in the 1920s there was a fellow named Hugo Gernsback who edited a science fiction magazine named Amazing Stories. Because he encouraged readers to write in to the magazine, he became the seed around which science fiction fandom crystallized. By the mid-fifties, science fiction fandom was a lively subculture. There were science fiction fan clubs in almost every major city. Fans wrote fanzines, attended conventions and handed out awards for the books and stories that amazed them the most. Many fans even went on to become professional authors. (Ahem.)

At the 1964 World Science Fiction Convention in Chicago, Irwin Allen previewed his new science fiction show, and Gene Roddenberry previewed his. The fans yawned through Lost In Space, but they gave the Star Trek pilot a standing ovation – a fact which puzzled Irwin Allen to no end. He couldn’t see the difference between Roddenberry’s show and his own.

When Star Trek began broadcast on September 8, 1966, science fiction fans took it to heart….Lots of new people started showing up at science fiction conventions because they thought they would hear a lot more about Star Trek. But science fiction conventions are about a lot of things, not just a single television show.

He then discusses the schism between Trek fans and Trufans (an historical era in which a participated, making my transition from Trekkie to Fan), the advent of the first Trek cons and their ultimate commercialization.

Ultimately, in discussing what makes Star Trek so popular, he ties its appeal directly to the core of science fiction:

Star Trek has always suggested that we can change things for the better, if we choose to. If we choose to…

Later on, David gets very philosophical about both science fiction and Star Trek and concludes on a bit of a downer, stating that Trek has not lived up to its potential (which is a common refrain from those old enough to have grown up with the show and all of its subsequent iterations) and ultimately lays the blame at our own feet; we need to take the lessons of Star Trek and move beyond them. I sense a bit of frustration here that has been somewhat mitigated by developments over the past 8 years. Perhaps inspired by this editorial, I hear more and more people who discuss this show talking about choosing to apply the show’s lessons as opposed to fetishizing it.

Saywer’s opening intro discussed his personal involvement with the show and serves as the perfect example of what can happen to an individual inspired by this show.

Spinrad discusses the fact that Star Trek created the mass audience for television science fiction, and how Roddenberry engaged with the fan community to make that happen. In light of recent discussions regarding our literature, I found the following to be particularly trenchant:

…by the 1960s, science fiction had evolved into something largely impenetrable to anyone who was not a regular science fiction reader.

The real stuff dealt with alien civilizations, faster-than-light space travel….And because it had been written for a limited, educated, in-group audience for so long, it had long since come to be written without compromise, without any real attempt to make it transparent to anyone unfamiaair with the conventions, imagery and secret language.

This in a way, was a literary strength. Most science fiction writers felt they had no chance of reaching a general audience, so they felt free to write for a theoretical ideal audience – the fans and regular readers, who understood the conventions and the special language, for whom the recondite imagery held meaning, who were, generally speaking, scientifically literate…This enabled science fiction writers at their best to produce work without intellectual compromise.

But this literary strength was a commercial weakness…when writers did try to reach a wider audience, they usually did it by watering the stuff down…by patronizing the general public.

Hmmm. (Seems we’ve discussed the importance and influence of the SF Ghetto before…)

D.C. Fontana, apparently loved by everyone she worked with, writes about what it was like to actually be in the center of Star Trek while it was happening:

Actually, the ear problem was the reason the Klingons our most useful villains.

(Making Spock’s, other Vulcan and Romulan ear tips was particularly problematic back in the day; aliens with no ear tips were cheaper to produce.)

Echoing Spinrad’s words, D.C. has this to say in her conclusion:

We were not writing for kids; we never talked down to our audience. We wanted the best. We wanted the viewers of Star Trek to soar with us – and they did.

Speaking of ears, the preceding are words that I think should be constantly whispered into the ears of every would-be director of theatrical science fiction.

Everyone else contributing to this volume has a deep appreciation for and understanding of science fiction and the role that Star Trek has played. It’s quite compelling to read how a single concept – that we can actually create the kind of future we will live in – has expressed itself through the lives of these authors and, in turn, how they have passed that concept on to us.

I think it bears repeating in these days of post-apocalyptic, zombie-infested futures:

We can change things for the better, if we choose to. If we choose to.

*I know, Trekkie or Trekker. It’s a bone of contention. But I’ll stick with the nomenclature I was introduced to when I attended my first Trek con in 1973.