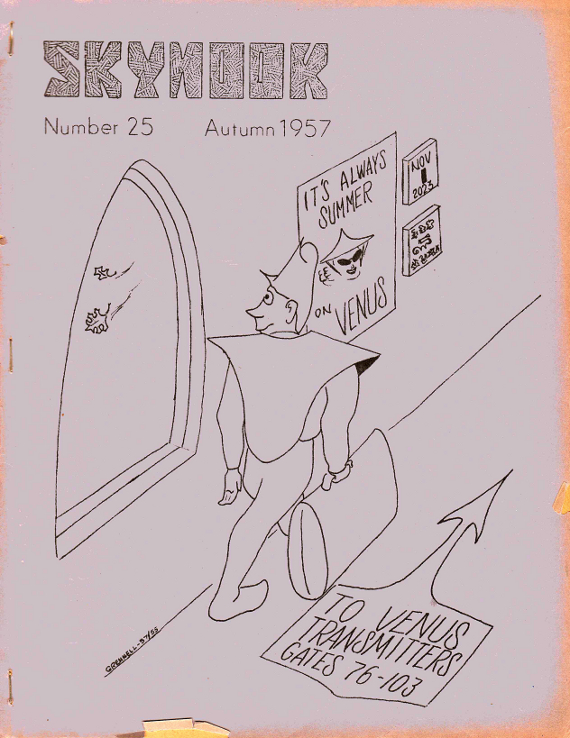

Fanzine reviewed: SKYHOOK (#25).

Skyhook (#25) – Autumn 1957

Faneds: Red Boggs & Marion Z. Bradley. American Reviewzine.

First off, this is part of the George Metzger donation to the BCSFA archive. Consequently it is delightful to read in Bogg’s “Twippledop” editorial that: “George E. Metzger, Shkk’s new artist, is 18 years old and a freshman at Yuba College. He’d like to attend art school later and become ‘a famous cartoonist’ with ‘lotta money, big house, large den, swords on the wall, and a guillotine in the corner for curing headaches.’ He lives in Oroville, California…”

Today he lives in an apartment in Vancouver near False Creek, may or may not have a large den, or swords, does not have a guillotine (as far as I know), and definitely does not possess a “lotta money”. He is famous for the silk-screened rock concert posters he produced in Frisco during the mid-1960s, for his numerous and varied comic art, is essentially retired, and still dabbles in silk-screening from time to time. Two of his article illos from issue #25 are reproduced in this article.

Harry Warner Jr. described SKYHOOK as “one of the most literate, brilliant fanzines of the 1950s.”

And Dick Ryan, writing in the letter column, states “The words ‘a quarterly review of science fiction’ define SKYHOOK much more truly, I think, than “individualist quarterly.” In other words, SKYHOOK was devoted to book reviews.

This issue, which I assume is representative of most issues, is packed with reviews, some of which are profoundly deep, complicated, and thought-provoking. Naturally I’m skipping those, being intent on meeting my CLUBHOUSE deadline, and will quote from the bits that interest me as my eye-tracks stomp through the pages.

Even the editorial is mostly book and magazine reviews. Boggs reports on an assault on the “new” writing evident in 1957, an attack which would probably bring tears of joy to the recent “Sad Puppies” movement. Kenneth Rexwroth’s “Disengagement, the Art of the Beat Generation” takes aim squarely at Judith Merril and her ilk.

“The most shocking example of this forced perversion,’ Rexroth says, ‘is the homey science fiction storey, usually written by a woman, in which a one-to-one correlation has been made for the commodity-ridden tale of domestic whimsy, the standby of magazines given away in the chain groceries.”

“In writers like Judith Merril the space pilot and his bride bat the badinage back and forth while the robot maid makes breakfast in the jet-propelled Lucite orange squeezer and the electronic bacon rotoboiler, dropping pearls of dry assembly plant wisdom (like plantation wisdom but drier) all the whilst.”

To this Boggs rather surprisingly comments: “This is a pretty exact description of a whole area of GALAXY fiction and of much F&SF fiction, though – to be fair – the ‘homey science fiction story’ is a more characteristic product of Margaret St Clair and others than of Judy.”

Then Boggs quotes a time magazine review of THE YEAR’S GREATEST SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY, a 1957 anthology edited by Merril, which “…compared ‘1957’s SF’ unfavorably with Jules Verne because current sf deals with ‘inhuman humans’ who ‘as characters… are deader than the planets they visit [and] as explorers… are about as intrepid as a pack of apartment-house janitors.’”

The reviewer than quoted Merril from her book “To be good science fiction, a story must contain a rare blend of intellection and emotion; puzzle and plot must be integrally related in such a way that the human problem arises out of the idea-extrapolation, and the resolution of the one is impossible without the solution to the other.”

To this the reviewer declared “No horror in this anthology is so appalling as the fact that at this very moment there is a mind-matrix around that is capable of writing such sentences in the belief that they may mean something.”

Even more extraordinary, Boggs comments: I can’t blame the reviewer for his remarks, however. I dislike Miss Merril’s kindergarten-teacher attitude: ‘Isn’t everything just too chummy for words,’ she seems to say, ‘and isn’t everybody so glad he came?’ Surely Judy more than almost anyone realizes that science fiction is really in a bad way, that everything is corrupt to the toenails, and that nobody is very happy with 1957’s SF.”

“But she has a contract to fulfill, and has to sell her “Best” collection to the public somehow. She thinks she can foist it on them most easily by insisting that it’s wonderful stuff. No doubt she knows that sf specialists realize the truth. But the Time Magazine review may prove that even non-specialists find her attitude as infuriating as I do, and aren’t fooled.”

Here in Canada, where Judy eventually settled in the early sixties (in Toronto), these words amount to blasphemy. Merril is a seminal influence on modern Canadian SF&F, and her memory is esteemed and honoured – by academics especially – to the point of sainthood. A patron saint really, as her example and teachings inspired so many others. Consequently, to come across an opinion of this nature is positively shocking. Myself, I have read nothing of hers and have no opinion of my own. Possibly the truth lies somewhere between the two polar opposites expressed above.

At any rate, it is evident that not everyone welcomed the early beginnings of “New SF.”

Dean Grennell [famous for his GRUE fanzine] contributes some observations on SF and fandom: “The fan press sometimes seems to lean a shade heavily to discussions of conventions, feuds, fannish projects, polls, and power politics, with relatively little discussion of science fiction itself… I say there is excellent reason to discuss science fiction in magazines such as this: not because it is the Fitting and Proper Thing to Do, but because it is rather good fun.”

In that spirit he claims “The primest slice of the whole science-fictional roast, in the opinion of many, including this writer, is the four-year output of ASTOUNDING spanning the years 1938 to 1942… This was the golden age of science fiction, in the years before the medium was so heavily hag-ridden with crackpot cults, before the cliches became clichés, before the involuted and skilfully-handled cliché became, itself, a cliché. It was a time when most of the best-regarded names in the field today were building their reputations and, therefore, turning out some of the finest work of which they were capable.”

“Campbell seemed, in those days, to be turning up exciting new talent with nearly every issue: Heinlein, van Vogt, Gold, Asimov, de Camp, Boucher, Clement, and a chap named Hubbard. One might have thought he was finding them under flat rocks, from their profusion if not their output…”

Hmm, not sure that last comment is meant as a compliment. At any rate Grennell admits he might be suffering from personal bias, contrasting his first, limited personal exposure to SF to the contemporary (1957) “flood” of SF books and magazines:

“Precisely how much of the rosy haze of nostalgia rises from the fact that, in those days, any single story represented a much greater percentage of my total experience with science fiction is hard to say. A drop of water, flicked onto your dry skin, will make a much more memorable impression than will any single drop when you are totally immersed.”

Good point that.

In “A is for Atom” Fred Chapell weighs in on, among others, A.E. van Vogt and Robert Heinlein.

“When a reviewer calls a novel van Vogtian, he usually means that it is complicated in plot… Van Vogt isn’t complicated; he’s complex. He uses, to my taste, an unnecessarily overburdening method of writing which doesn’t exactly enhance the clarity of his stuff. He writes in scenes of 800 words, and introduces a new idea in every scene. This is of course no hard and fast rule, but he does stick to it fairly consistently, and it’s not a good way to write. Novels in scenes of 800 words are pretty choppy.”

“The difference between van Vogt and almost every other writer… is one of conception… the world of NULL-A is a truly complex society, but when I read the book, I can’t find a single “set” speech or passage of omniscient prose at all which explains the structure of that society. Maybe I’m wrong, but I think that van Vogt’s plot complexity serves a useful purpose: it gives you an intimation of the complexity of the society within which the story is set. These other writers work differently: after the narrative has started and you’re pretty well hooked, they give you a pat explanation of the society and then they let the story go on. After that, it is the story that’s complicated, not the setup.”

“Robert Heinlein’s work, however, usually breathes the sort of atmosphere we are most likely to label truly science-fictional. Heinlein’s atmosphere is as bright and sunny as Easter Sunday in contrast to van Vogt’s dark Thursday mood. The reason is of course a technical one. We grasp Heinlein’s characters and their motives easily – perhaps too easily – hence the plot, for Heinlein’s ratio of character to plot is usually about one-to-one, while van Vogt’s characters usually don’t know what’s happening to them about half the time and don’t know, the rest of the time, what they’re doing and why.”

“It’s going too far to call Heinlein’s characters active and van Vogt’s passive, but one gets the impression that most characters in van Vogt are victims of their setups… There’s another difference too: ever notice how utilitarian everything is in Heinlein? Everything is of use, everything is nice and neat, everything comes out even. Heinlein is an incurable optimist… Van Vogt isn’t a rat-ridden pessimist, of course, but his clutching at such straws as scientism and Dianetics suggests a tortured sensibility and a raw sensitivity to evil. With these bits of aid, flimsy as they are, he is able to see – though not as through a glass, darkly. Rather, as through the dark, glassily.”

Jim Harmon has a rather interesting paragraph on Heinlein as well:

“I am about to make a statement I am sure I will regret and may recant under the furious assault: Robert Heinlein is not the greatest writer of science fiction. The opening chapters of CITIZEN OF THE GALAXY (ASF, Sep 1957) have finally convinced me. This is just another goddamned adventure story! Sure, it has psychological, symbolical, and philosophical over and undertones but, by damn, any professional writer telling an action story of the fourteenth or the fortieth century would put these in or he wouldn’t be selling. These are the very marks of the professional writer and praising a scribe for including them is as pointless as congratulating him for having characters or a plot. Heinlein is the absolute master of all the subtle and the blatant techniques of commercial fiction but his work can be broken to its quantum elements, its building blocks. Elevating all these techniques to such a high level is admirable, but like making a work of art out of a comic strip (a la Walt Kelly and Will Eisner) it is also a pitiful waste of talent.”

Ahh, uhmmm. I suspect there are graphic art fans who beg to differ, not to mention Heinlein fans. After all, both Kelly and Eisner were near-genius level comic artists, and Heinlein much the same for his writing (until he got into the habit of writing obscenely bloated drivel, but that’s a topic for another column).

And finally (bear in mind I’m leaving mention of a number of worthy articles out) Associate Editor Marion Zimmer Bradley has interesting things to say when reviewing THE 13TH IMMORTAL and MASTER OF LIFE AND DEATH by Robert Silverberg.

“When I read my first Bob Silverberg story, which was called, if memory serves me rightly, THE MARTIAN, I made one of those snap judgements to which all opinionated people are prone, that here was a writer of sensitivity and perception, a little inclined toward pessimism and the precocious misery which haunts only septuagenarians and teenagers. This early judgement was a little blunted by a whole procession of readable, interesting, and thoroughly unmemorable stories of the competent-hack variety, appearing in most of the leading SF magazines, not one of which remains in my memory as either good or bad. Silverberg, I understand, forthrightly refers to himself as a ‘fiction factory,’ and for a while seemed to be attempting to top the record of the late Ray Cummings for both output and competent mediocrity.”

She does find, much to her surprise, good things to say about both books.

“The best thing one can say of the plot of THE 13TH IMMORTAL is that it is a compliment to Bob Silverberg’s talent that such a mishmash of weary clichés could be made into a readable novel at all… It is told with a bright perception of movement which indicates clear visualization, and has a freshness incredible in so seasoned a young writer, a freshness that at times approaches naïveté.”

“MASTER OF LIFE AND DEATH… is a hint that Silverberg may stand at the head of a rebellion against the sordid and uniformly dull tales of which we get too many today… the twists and turns are entirely unpredictable and the story continues to surprise the reader up to the last page…”

“From reading these two novels, I would say that Silverberg, right now, is poised at some sort of turning point in his career. He can degenerate into a comfortable, profitable hackmanship… Or, having early acquired the basic tools of his trade… can go on to develop his characterization (which seems to be his main weakness at present), enlarge his basic control of plot, broaden his vision, and give free rein to his essential sensitivities… He can also, if he uses his talents in their broadest way, grow perhaps into another Heinlein or Kuttner, whose prolific outputs have in no way damaged their perceptive tendrils.”

“It will be interesting, say in five years, to read another pair of Silverberg novels and see which choice he has made.”

Try twenty years or so. Circa 1976 Robert Silverberg took a four-year break from writing despite having won a Hugo and three Nebula’s by that time, as well as earning a reputation for excellent short fiction. In 1980 he came roaring back with LORD VALENTINE’S CASTLE and many subsequent works.

I quote the Clute/Nicholls ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE FICTION: “”He [Silverberg] remains one of the most imaginative and versatile writers ever to have been involved with SF. His productivity has seemed almost superhuman, and his abrupt metamorphosis from a writer of standardized pulp fiction into a prose artist was an accomplishment unparalleled within the field.”

Seems, way back in 1957, Marion Zimmer Bradley was being very prescient.

BY THE WAY:

You can find a fantastic collection of zines at: Efanzines

You can find yet more zines at: Fanac Fan History Project

You can find a quite good selection of Canadian zines at: Canadian SF Fanzine Archive

And check out my brand new website devoted to my OBIR Magazine, which is entirely devoted to reviews of Canadian Speculative Fiction. Found at OBIR Magazine

Fanzine reviewed: SKYHOOK (#25).

Fanzine reviewed: SKYHOOK (#25).