Other short stories from the 1978 Puffin Publishing anthology “The Worlds of Arthur C. Clarke – Of Time and Stars” have been reviewed here, primarily looking at the author’s ability to look at the future with an astute eye and presenting it with his natural prose that always seems to put the reader at ease. But in Robin Hood, F.R.S., Clarke has some questionable science elements. Though pivotal to the plot and written nearly sixty years ago, the author’s futuristic creativity leaves us with questions and doubt rather than the typical wonder we’ve come to expect from him.

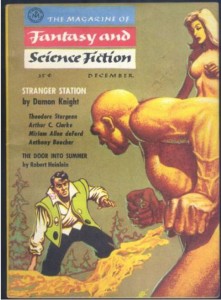

December 1956

First appearing as a stand-alone story in the December 1956 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction Vol 11, No 6 (Fantasy House, Inc.), Robin Hood, F.R.S. is the second of six linked works by Clarke originally titled Venture to the Moon and commissioned earlier in 1956 for London’s Evening Standard.

The story centers on a lunar expedition’s attempt to retrieve the delivered materials from an errant “radar-controlled” supply rocket that landed high upon the summit of the only unclimbable hill in the area. Professor Trevor Williams is the team’s astronomer, but he also happens to be a former archery champion of Wales (a little background to enhance the story’s title). So with some ingenuity, he helps the expedition retrieve the stranded supplies using a makeshift bow and special arrows.

This ingenuity is where the story falters and the questions begin.

The professor is presented as having an astute understanding of the physics of a vacuum and makes the necessary alterations to the arrows:

“The arrows, however, were the really interesting feature. To give them stability on the airless moon, where, of course, feathers would be useless, Trevor had managed to rifle them. There was a little gadget on the bow that set them spinning, like bullets, when they were fired, so that they kept on course when they left the bow.”

Huh? If feathers are useless in guiding the arrow in a vacuum, wouldn’t the spinning from rifling be just as useless? With no atmosphere to provide friction, wouldn’t an arrow tumbling end over as if thrown for a dog fetching a stick end be just as effective as one going true and straight?

Then comes a question of gravity:

“He tied one end to his arrow, drew the bow, and aimed it experimentally straight towards the stars. The arrow rose a little more than half the height of the cliff; then the weight of the line pulled it back.”

Okay, the gravity of the moon is less than the earth, but this still sounds reasonable so we continue with the adventure. But the following solution sounds a little perplexing and we are distracted once again.

“This time, however, Trevor was not using a single arrow. He attached four to the line, at two-hundred-yard intervals. And I shall never forget that incongruous spectacle of the space-suited figure, gleaming in the last rays of the setting sun, as it drew its bow against the sky.”

“The arrow sped towards the stars, and before it had lifted more than fifty feet Trevor was already fitting the second one to his improvised bow. It raced after its predecessor, carrying the other end of the loop that was now being hoisted into space. Almost at once the third followed, lifting its section of line – and I swear that the fourth arrow, with its section, was on the way before the first had noticeably slackened its momentum.”

The success of this scenario sounds questionable at best. Having had past experience with archery and considering the speed of an arrow, especially considering the compensation in a vacuum, one would need the superhero skills and speed of a character Hawkeye to accomplish such a feet. Even taking in the factor of a weaker gravity, the precision just doesn’t sound right.

If the Discovery Channel’s popular Mythbusters ever decided to look at the science behind science fiction literature, this would be a fun one to see how it turns out.

My education in physics is limited at best. But as a dedicated reader of the genre, making sure the science doesn’t take away from the story is a key element. And if the theme of the story is centered on the science, it should also be plausible.

It’s kinda like making the leap from drawing blood from mosquitos encased in amber to crediting midi-clorians behind the pervasive Force. It is the line in the sand between science fiction and fantasy.

Given that Robin Hood, F.R.S. was written so long ago, any subtle flaws in accuracy can be forgivable. But when fandom grows accustom to the accuracy and insightfulness of a forward thinking author like Arthur C. Clarke, any subtle flaws can become magnified. It might be the rare occasion that a Clarke story can be considered dated.