I have always had an interest in history; I find the detail fascinating, the connections revealing and have come to believe that the study of history ranks among our best tools for preparing for the future. Naturally, science fiction is the other tool at our disposal, so I suppose these two interests of mine say something about the way I view and approach the world.

The preceding is why I’ve studied fan history, genre history and continue to do so. It’s what drew me to Amazing Stories in the first place – the world’s first science fiction magazine.

I was fortunate enough to be going to public school when some of the first classes in science fiction as literature were offered (naturally I opted to take those classes); I was fortunate enough to make the acquaintance and friendship of Gary Farber, a student of fan (and fanzine) history, and very marginally assisted him in putting together one of the first fan history/fanzine history rooms at a Worldcon (my assistance was largely confined to carrying boxes of fanzines from one place to another).

Through all of those years my exposure to formal SF history were the writings of scholars such as James Gunn (Alternate Worlds), Brian Aldiss (Trillion Year Spree), Sam Lundwall (SF: What’s It All About) and a few other texts I’ve since forgotten.

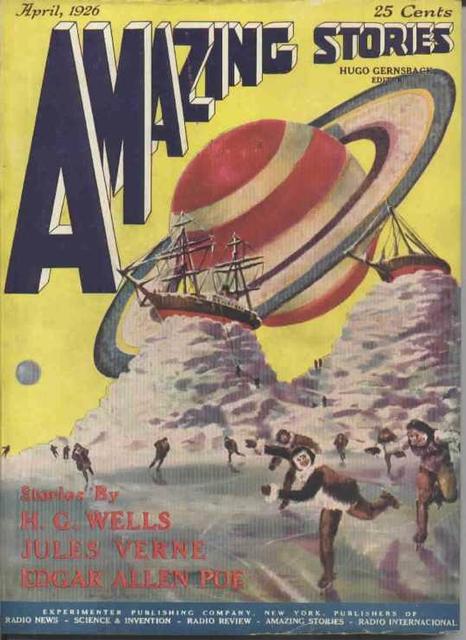

These authors (who I hasten to add I greatly admire) all largely presented one school of thought on the origins and evolution of what has come to be called science fiction. That history of evolution is that science fiction has largely always been with us – probably going all the way back to campfire tales; starting with the Epic of Gilgamesh, through Greek plays, Plato’s The Republic an early utopian example; through Cyrano de Bergerac’s trips into outer space, Lucien, into the Gothic realm, Castle of Otranto, Shelley’s Frankenstein and on through Poe, Verne, Wells and into the 20th century, finally finding a (poor paying) home in the new magazine of one eccentric publisher and advocate of science – Hugo Gernsback.

My own discovery of Amazing Stories somewhat parallels the work of those previously cited authors, digging down through layers of history until finally uncovering the UR layer; television kiddie fare to Scholastic Books for younguns; digging deeper, a discovery of Heinlein Juvenovels, trips to the bookstore uncovering anthologies, anthologies revealing the existence of magazines, a field trip to a used book stall finally yielding the first concrete evidence of such a wonderous thing:

This is the cover art for the very first science fiction magazine I ever purchased – along with the others shown below – 25 cents each or five for a dollar. I spent the dollar.

(I discovered that the magazines, arriving on a monthly schedule, were a better source for finding new authors than the ‘static’ anthologies were.)

The interesting thing about my discoveries was that they seemed to support the “SF has always been with us” school of evolutionary thought; I was always somewhat disappointed that Amazing Stories only seemed to enjoy an also ran status, the grand old man in his dotage; little time or attention was paid to what seemed to me to be an important evolutionary step: the actual identification of the genre as a genre, and, other than the Hugo Awards (which have achieved a status all their own largely divorced from their namesake and the magazine he founded), most mentions of Hugo Gernsback were of the negative variety; Aldiss and others preferred to mention his failures rather than his achievements.

Here, I enter the picture again; Ted White ran a re-examination of the history of Amazing’s bankruptcy (actually the Experimenter Publishing Company’s) and I eagerly went out and double-checked the facts in Steve Perry’s essay, confirming them in a letter to the magazine that was mentioned by White in his editorial on the subject. But that little episode faded as time went by and we were back to Amazing’s perceived second-class status.

I had several letters published in the magazine and received numerous rejection slips – both of which I’m proud of. And in the late 70s I made the acquaintance of one Bob Madle (a member of First Fandom and huge book & magazine collector) who would offer his own version of the history of the genre and fandom, and would eventually find and sell me a copy of the very first issue of Amazing Stories (which of course I still have).

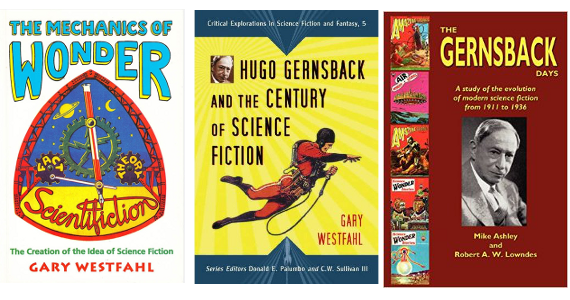

Now I will pause to mention that I am not the most well-heeled individual within fandom and there is always tension when it comes to book buying time; I’m inclined to pick up histories and other non-fiction related to the genre, but that inclination often falls victim to my need to be keeping up with the Jones’ in the fiction department. This is to say that there are numerous scholarly works that I am aware of and equally aware that I certainly ought to have read them by now, but “dry academe” has suffered at the hands of authors like Scalzi, Jemisin, Stross, Stephenson, etc. Until this past holiday, when I determined that I really could not wait any longer and picked up a host of histories, written by some of the finest SF historians there are. Specifically, Gary Westfahl’s The Mechanics of Wonder and Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction and Mike Ashley & Robert A.W. Lowndes’s The Gernsback Days.

I’m nearly through the first of these and have to say – Westfahl does a masterful job of destroying the previously ascendant version of the genre’s history; various pieces I’ve read by Ashley (who is known for his unparalleled knowledge of the magazine history of the field) lead me to believe that he and Lowndes will be doing an equally wonderful job of correcting the false idea that science fiction began at any time other than on April, 1926, when Amazing Stories first hit the stands.

Reading these books, I imagine that I must feel somewhat like Schliemann did when he broke ground on Troy; no one gave any credence to his theory that the city of yore was real and occupied a real place. But Schliemann kept on digging and digging and digging – and then turned the entire world of archaeology on its ear.

Westfahl’s and Ashley’s theories of the history of the creation of the Science Fiction genre ring true; we can and should incorporate those works that predated Amazing as valuable signposts along the way to genre (Gernsback used Poe and Verne and Wells as illustrative examples of what he meant when he defined SF), but if we want to be able to have a true understanding of the genre and deal with the real, it is high time that we return the accolades to Gernsback, who is truly the Father of Science Fiction.

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.

It’s interesting how much of our personal history–when it comes to fandom and SF–dovetails; after I became the fan columnist in the ’80s I found out my paternal grandfather was a regular reader of Amazing. (And when I was in high school, history classes–American and World–were among my favourites!)

There are many more knowledgeable fans (about fandom) than I; there are older fans (in fandom) than I–but I venture to say that your enthusiasm and mine are pretty much the same! I’m glad you revived the “grand old man” of SF; and I’m glad to be part of its reimagining. In any way!

Thanks, Steve!