Chances are that if you’re reading this, you’re some kind of gamer, whether it be the old non-electronic types of game like tennis, poker, bowling or board games; newer games like RPGs and Magic®-type card games, electronic console games (Xbox 360 or Xbox 1, PS/3 or PS/4, Wii) handheld games like PS Vita, Nintendo DS (various versions), PC games or whatever… we SF/F types have a predilection for games. (Given the controversy over the so-called “GamerGate,” I will only say that some games appear to be hostile to the non-male player/developer, and leave it at that. This blog is in no way attempting to make any kind of statement about gender roles in gaming.) I’d like to talk about some older “console” games and what I like in gaming.

My own involvement with electronic/computerized games goes back to 1965 or so; when attending what was then Everett Junior College (now Community College), I was majoring in “Computer Science,” and we wrote our programs to run on an IBM 1620 mini-mainframe. The 1620 used core memory, disk packs and tape as auxiliaries, and could be programmed via Hollerith punch cards. (If you don’t know what core memory or disk packs are, don’t worry. They were forerunners of RAM and the floppy disk. All the peripherals, like card punches, were programmed with jumper jacks. It was a very “hands-on” time.) Its main output was a teletype-like printer (see Figure 2); there was no video output. My friends and I soon learned how to make a “slot machine” program that would output random symbols in a slot-wheel-like printout. That was my first electronic game. (Another “cool” feat of the 1620 was that if you put an AM radio on top of the console and tuned it to a blank area on the dial, with the right program running the RF interference patterns could make it play “music”—kind of raw tones, but it could play actual tunes with the right program. I can’t remember the name of the classmate who discovered how to do that.) If you care at all, we programmed in machine language (mostly) and Fortran, which I’d had a bit of a grounding in when I took a summer class in WATFOR (Fortran version 4) at the University of Washington when I was in high school.

If I remember correctly, we were also trying to make text-based games similar to what they were doing at M.I.T. (the Massachusetts Institute of Technology); according to what we’d been told they had a video (!) output and had come up with a game called something like Space Wars, where you guided a little spaceship among the stars. We had no video, but we sure wasted a giant amount of computer paper trying to do a text-based version! (We also were attempting to do our own version of the Cave Adventure text adventure they’d come up with.) However, the Viet Nam war was raging, and I was soon out of EJC and into the U.S. Navy. (Never went to Viet Nam, either.) In the Navy, I was sent to “Deck” division—the swabbies, as we were called—who swabbed the deck, chipped and painted (slogan: “If it moves, salute it! If it doesn’t, paint it!”) I was stationed upon the U.S.S. Twining (DD-540), an old World War II destroyer, which had taken a torpedo amidships during one of the South Seas battles, but had been repaired and was still chugging along. I, personally, must have painted that ship three times while I was aboard.

An interesting side note about the Twining, which was not only a veteran of World War II, but had also served two tours during the so-called “Korean Conflict”: if you’ve seen the movie It Came From Beneath the Sea, featuring Ray Harryhausen’s famous “Quintopus” (the producers didn’t have enough money to pay Harryhausen for an 8-tentacled creature, I’ve been told), then you’ve seen the Twining. It appears, I think, twice in the movie, steaming along the California coast. After its long and distinguished military career, the Twining became a trainer for Naval Reservists, and was stationed permanently—until she was decommissioned, shortly after I left her—at Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay, just off the Oakland Bay Bridge.

Anyway, on the Twining I couldn’t study computers, but I got a couple of books about how to be a Radioman, and quickly learned Morse Code and a bunch of other stuff—yes, Morse was still a requirement in those days—and took some tests and became a Radioman, keeping my interest in electronics alive. In my spare time, since we were more or less in San Francisco (!), I spent many happy days and weeks in “hippiedom,” the area known as Haight-Ashbury. (Yes, I can remember the sixties, and yes, I was there.) So let’s skip forward a few years to Pullman, Washington in the 1970s.

Back to school on the G.I. Bill, I was studying computer science again; after such a while and so much water under the… ship, I was getting impatient with classroom work, so I started spending a pretty fair amount of time in the Student Union Building, playing pool and pinball, and getting well acquainted with the guy who serviced the pinball machines and the jukebox. Eventually, I dropped out of school and got a job servicing pinballs and jukeboxes, mainly because it was pretty elementary electronics and mechanics. I worked for a number of vendors in the Pullman area, eventually working for a fellow who had bought out some of the other guys—and in the middle of all this, a man named Nolan Bushnell had brought out the first commercial video game, called Computer Space (Figure 4). It came in a futuristic-looking metal-flake case; we had several, all red. The game, as I recall it, was very similar to the spaceship part of Asteroids, where your rocket had to fight flying saucers against a “star field” background. Then came Pong (Figure 1). I quickly learned how to service (and play) these two games, very nearly winning the Sears Pong competition in Pullman when, a couple of years later, Atari (Bushnell’s company) brought out the first home version through Sears.

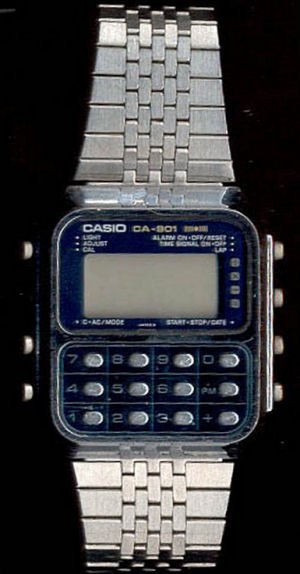

So that was the beginning of today’s computer/console/electronic gaming industry. Most of the computer consoles were coin-operated and played a single game, like Pong, and Asteroids; later we got colour games like Centipede, Dig Dug, Pole Position, Donkey Kong and so on. And I’ve been computer gaming during that whole period, as much as I could—I’ve had computer games on watches, made by the Japanese company Casio, and I’ve owned handheld games of various kinds; as a matter of fact, I still own a Milton-Bradley Microvision and several cartridges. As far as I know, this was the first portable game system with changeable cartridges, though the gameplay’s nothing to shout about, really. I was quite envious when a couple of my friends had some tiny portable consoles for games like Tank Battle or Ms. Pac-Man—even a handheld Vectrex, which had vector graphics, but I didn’t get my own “console” game until I got the Atari 2600. (The first one of those home console types, as far as I know, was the Magnavox Odyssey. I never did get one of those.) Back to handhelds, I had—and still have—an Atari Lynx and a Nintendo Gameboy Colour. (And in more modern handhelds, I have a Sony PSP (PlayStation Plus) and a Nintendo DS Lite.)

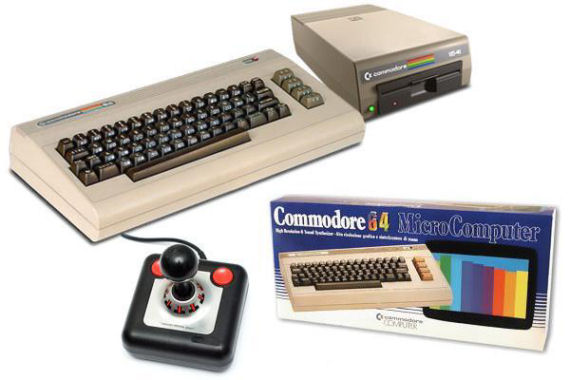

The 2600 had some great titles, but the graphics and gameplay were not up to video arcade standards by any means… not that most of the previous home consoles had been either. Home gaming didn’t really improve (in my opinion) until Nintendo or Sega brought out their consoles: the NES, or Nintendo Entertainment System, and the Sega Genesis. I still have an Atari 2600 and a number of cartridges. Somewhere in there, besides game consoles—and there were dozens of them from the 1970s to the 2000s—we started seeing home computers, like the Apple IIe and the Commodore 64 (which I have as well… including most of the peripherals. I’m thinking of getting an upgrade to USB for it off eBay.). I also have a Sega Genesis and a Sony Dreamcast—the true progenitor of the PS/3.

But none of those—even the ones which purported to have “arcade” titles, could match the excitement, graphics and gameplay of the arcade games. (How’s that for a roundabout way of getting to the point?) Here it is, thirty or more years later, and I still yearn for those old arcade games… don’t get me wrong—I love the gameplay and graphics of some of my Xbox 360 or PS/3 games, but I still love the “good old stuff.”

Which brings me to the names of some of my favourites. I’m going to stick with the games that—even when I was working on arcade games as a technician—sucked up a lot of quarters.

Let’s start with what might be the earliest really addictive arcade video game: I refer, of course, to Midway’s (1978) Space Invaders. Originally put out in black and white, the game was later “coloured” by having coloured cellophane over the monitor so that each couple of rows of advancing aliens could be a different colour. Primitive graphics but your heartbeat increased as the aliens got closer and faster. That was followed by, in 1979, Galaxian (also Midway), which was actually in colour. These aliens actually broke formation and swooped down to try to zap you. Equally addicting, in my opinion.

Atari struck back with vector graphics (all 1979 until Battlezone), which added a certain smoothness to the look and animation of these games: Lunar Lander, Asteroids and Battlezone. As an SF/F fan, how could I not play the first two games? And with Battlezone, you were using two joysticks to control a futuristic tank, peeping through the viewport at a green screen and trying to get them before they got you. (It was made harder by the fact that you could only shoot one shot at a time, and your shot had to either hit something or disappear over the horizon before you could shoot again. And I shouldn’t fail to mention the sound effects of all these games, either. Midway’s games had a beat that increased with time, until your heart was pounding; Asteroids also had an increasing bass, along with the high-pitched warble of the flying saucers that came in at random times and shot at you; Battlezone had the grumbling engine of a tank as you manipulated the two joysticks, and also had a warbling “flying saucer.”

In 1980, there was a pitched battle among Stern, Atari, Namco, Midway and Williams (which was also a maker of juke boxes and pinballs—none of the others did except Midway). We got, in fairly quick succession, Berzerk, Centipede, Defender, Missile Command and Pac Man, along with a couple of others that didn’t make big splashes, except for Rally-X, a driving game. Centipede and Missile Command were the first two trackball machines; Centipede’s action was vertical, while Missile Command gave you more freedom to try to hit the incoming missiles and defend your three cities until you were overwhelmed and the screen informed you “Game Over.” That was a great game! Also, in 1980, Cinematronics and Atari had two vector games that were quite good—Star Castle, which like Space Invaders had coloured overlays; and Atari’s Tempest, which was the first true colour vector game—it was extremely fast-paced and hard to master in the higher levels.

1981 through 1985 brought some of the most iconic arcade video games ever: we had (in no particular order): Wizard of Wor; Donkey Kong, which introduced Mario to the world; Frogger; Galaga—what a great game; it was like Galaxian, only with better graphics and more intense gameplay!; Ms. Pac-Man—an obvious attempt to bring in the female gamers; Qix; Burger Time; Dig Dug; Donkey Kong Junior; Joust (knights mounted on ostriches trying to scoop up pterodactyl eggs—c’mon! What could be more SF/F?; Moon Patrol (one of the first side-scrollers); Pengo; Pole Position (another driving game); Q*bert; Robotron; Time Pilot; Tron; Xevious; Zaxxon; Dragon’s Lair (one of the first ever video-disc-based games. The gameplay was a simple A/B choice at a number of vertices, but the graphics were Don Bluth quality!); Elevator Action; Gyruss; Mappy; Mario Bros.; Spy Hunter (a vertical scroller); Star Wars and many more, like Rush’n Attack—based on a fictitious war against the Russians! (Cold War paranoia, anyone?). Don’t know why, but it kept me coming back. Looking back now, I must have spent many hundreds of dollars in these machines, even though I could legitimately play many of them for free (for a while, I managed an arcade). Then I moved to Canada, and pretty much stopped going to arcades.

In the 1990s, home computers, home game consoles and the like had replaced the video arcade in many people’s lives, and the arcade today is home mostly to the games that have controllers and/or game play that can’t be replicated at home; although there are wheel and pedal controllers for most consoles, a dedicated driving game offers a more realistic experience, for example. Shooting and hunting games, like Big Game or the bloodier House of the Dead, just can’t give you the same feel with a home controller; also games like Dance Dance Revolution work much better with an arcade game. So they’re holding their own, barely—most of the arcades I’ve seen lately are attached to or part of movie theatres to give the younger movie-goer something to do while they wait for their show to start.

But in the 2000s, an Italian guy, whose name I’ve forgotten (Nicola Salmoria), decided to see if he could replicate the hardware of the arcade video games—and M.A.M.E. (the Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator) was born; although most arcade games use copyrighted ROMs (Read-Only Memory chips), a lot of those games were no longer being produced and ROMs could be—ahem! “borrowed” from existing games and copied. The controls were emulated, as were the sound chips—although some sounds had to be replicated with MP3s—and today pretty much any arcade game of the past can be, if you’re not too picky about where you get the copyrighted ROMs, played at home; MAME (the periods are usually left out when writing the abbreviation) can play just about any game you have the ROM for—and some games are what’s called “abandonware,” which means the original maker is either out of business or is not particularly concerned with protecting his copyright—so you can freely download them from the internet.

There are a number of places you can play old games on the internet—either in your browser or by downloading an emulator; places like Game Owl, Games 4 Free and Game Oldies, if you look for them. And now we come to the newest member of the ‘80s arcade-lover’s team: The Internet Archive has just released its browser-based Java-based answer to MAME, called MESS, or JMESS, which allows you to play many games mentioned above and many which are not mentioned right in your browser (although I don’t see Rush’n Attack. Guess I’ll have to keep using MAME for that).

If you’re at all interested in playing these games, give MESS a shot and let me know whether you like it or not.

Next week, I hope to have a review of William Gibson’s new SF book—and it’s true SF, not just a “near-future” book like his Blue Ant stuff—called The Peripheral. I’m reading it now, and it’s exciting stuff! So stay tuned. Bill’s on his book tour now, heading for one or the other coasts even as I write this.

Please comment on this week’s column/blog entry. If you haven’t already registered—it’s free, and just takes a moment—go ahead and register here. You can also subscribe to my blog by checking the “Notify me of new posts” box. You can also comment on my Facebook page, or in the several Facebook groups where I publish a link to this column. I might not agree with your comments, but they’re all welcome, and don’t feel you have to agree with me to post a comment; my opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owners, editors, publishers or other bloggers. See you next week!

1 Comment