Read the previous chapters here: part 1 * part 2 * part 3

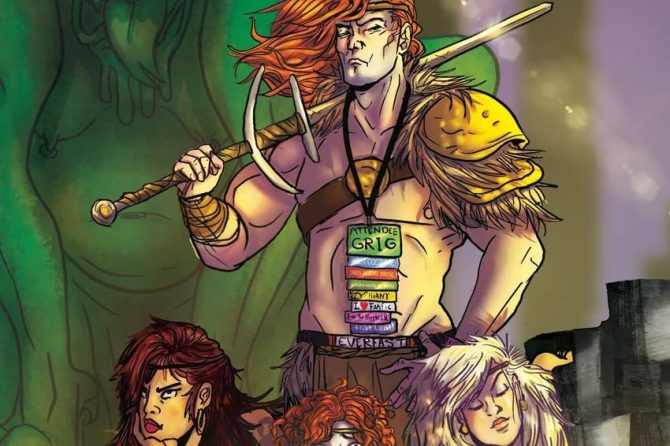

In the first three instalments of this mini series of blog posts, I have looked mainly at cover illustrations done for the various editions of the Earthsea books, from the 1970’s – when the original three books were first published – through to the re-editions in the 1990’s and early 2000’s, as well as cover illustrations for the second series of Earthsea books, which were written and published during this period. I have also had a look at the representation of the various characters in the 2006 Anime Gedo Senki, which is based on the Earthsea series, and a brief disgusted glance at the casting choices for the infamous 2004 TV production from the Sci-Fi Channel.

In this post, I would like to introduce my own visual interpretation of Earthsea and its places and characters. This series of 12 oil paintings was done between December 2008 and August 2010, when the series was exhibited – as Fantastic Journeys, for legal reasons which I will touch on briefly further down – at Thistle Hall in Wellington: my first solo exhibition of paintings, and thus a major milestone in my own development as a painter. Two additional paintings were added in 2012, when the series was exhibited again at the Events Centre in Carterton – bringing the total up to 14 paintings.

The reasons for embarking in this project were purely inspirational: I had been reading the Earthsea books, for a second or third time, during an extended holiday on the South Island, and some fairly fully formed images had begun to crowd in my head. Stuck on a campsite in Golden Bay on a rainy day toward the end of my trip, I sat down with a sketch pad, and in the space of some three hours, jotted down a complete series of thumbnails. About to thirds of those initial ideas ended up as finished paintings. It was good that I jotted them down, since it was going to take me a year and a half to paint them, and visions, much like dream images, have a tendency to wilt and fade when not attended to immediately, or stored for later use.

Some of the landscapes I had passed through on this trip, reformed themselves as various regions of Ursula Le Guin’s fictional realm: in particular, the dry and stony inland area of Central Otago, which had already stood in as “Rohan” in the Lord of the Rings movies, now became the desert of Atuan. To be sure, New Zealand lends itself quite well to stand in for a fictional island realm. There are other bits and pieces of actual landscapes to be found throughout a number of the other paintings.

I was having more trouble with some of the architectural bits and pieces: having grown up in Europe, I do have a pretty good idea of various historic architectural styles to steal and borrow for my pictures, but for purposes of actual reference, there is rather a dearth of it in New Zealand. I was desperately looking for a courtyard that could serve as a model for the Courtyard of the Fountain on Roke Island (which I pictured, rightly or wrongly, as a building in a medieval-ish or Renaissance-ish European style), and ended up taking my sketchpad with me to Europe when I went to visit my family that year.

This led, among other things, to an epic run-in with one of the guards at the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar (which houses one of my all time favourite paintings, the Isenheim altar piece, and moreover also sports just the right kind of courtyard) – who was acting like a complete nazi when I whipped my sketchpad out and started to work. The interaction ended with him tearing my budding sketch from the pad and crumpling it. Who would have known that sketching a picture could be such an illegal act. According to some people, only a dead artist is a good artist, evidently. But, that is a different story.

Most of all, I was of course concerned about being able to represent the main characters appropriately. The articles I have been reposting here were originally written for my newsletter in the process of my own grappling with this issue. Being aware of the author’s strong views on this topic, I was doing my best to be really meticulous in my representation of Ged, in particular – and I am not sure that I have succeeded. For as it soon turned out, it was again a problem of finding good reference.

American First Nation people are thin on the ground where I live. I spent quite some time finding photos on the internet, but working from a photo can never be a substitute for the complete impression an actual, living person makes. As I noted earlier, there is more that goes into ethnicity than just skin and hair colour: there is a repertory of gestures, facial expressions, and movements, of postures and moods, and it will always be easier to represent someone who is similar to the people in one’s immediate surroundings, than it is to paint a believable picture of a type of person one is less familiar with. Which is possibly the reason why my Archipelagans ended up rather more Polynesian looking.

Is this acceptable? Or did I fall into the racist trap that divides the world into “white” and “not-white”, and assumes that for a character like Ged, as long as his skin is the proper shade of not-white, any “exotic” ethnicity will do? Or is it simply a matter of the practicalities of how we create art? Perhaps a bit of all of that.

For a space of about 5 years, from 2007 until after I shifted out to Featherston, I regularly attended a life drawing session in Wellington – once, and sometimes twice a week. During the first four years, we had a decent variety of models – men, women, older, younger, slim, tall, short, sometimes even fat. But one thing they all had in common: they were, all of them, exclusively, Caucasian.

I am pretty sure that this was no evil racist plot on the part of the organizers: it would have had more to do with the availability of models. Life drawing – as in, the drawing of a nude model – is a quintessential part of the standard European style art curriculum, but it is a very culturally determined thing. I can easily imagine that people from other cultural backgrounds would find the idea of standing naked in front of a group of people sketching them, AND potentially making those sketches available for others to see, deeply uncomfortable. In fact, most European people who do not have a background in the arts would find the idea deeply uncomfortable.

But, how are we as artists supposed to broaden our repertory of how we represent people, if the models we get to practise our skills on, all belong to one particular ethnic group? Perhaps it is not so surprising after all that most of the illustrators I have presented in the previous three posts, have a knee jerk reaction to represent every character as white.

As to the life drawing classes: someone else evidently also became aware of this issue, for in the last few sessions I attended, we had one model who was mixed race African-Caucasian, and another who was Asian. Which was an eye opener, in that it made me realize how much of their ethnic identity was not just determined by physical aspects (such as body proportions), but by the way they moved and posed, and their repertory of gestures, which was particularly striking in the case of the Asian model.

I don’t know if Ursula Le Guin is aware of this series of images, or if she approves of them. I have written her at some point during this process, and included prints of the images I had completed by then, but instead got a reply from her agent warning me sternly not to use the name “Earthsea”, for some legal reasons that seemed to have to do with their ability to monetize the film rights at some point in the future (it was all a bit obscure to me). I won’t go into the details of this exchange, which was dissapointing for various reasons, not the least of them being the patronizing tone – and I should stress that I have no reason to assume that this represents the opinion of the author herself, who presumably just passed the matter on.

It was reason for me to do my own digging into the legal situation concerning works of art inspired by the writings of living authors: I should like to make it clear here that painting a visual version of a scene in a book is in no way a breach of anyone’s copyright, since copyright only applies to things “in material form”: an idea expressed in writing, and translated to a different artistic medium, does not fall under it. There seems to be rather a bit of confusion around this issue these days.

A word like “Earthsea”, or the various character and place names in the book, however, have “material form” and are therefore protected by copyright, which is why I cannot use them, and have therefore been forced to call this series, and the individual paintings, something else. My own personal opinion on this issue is that this is both disrespectful to the author, who should be given credit for suppling the idea and inspiration, and it takes away from the artwork, which was done explicitly to be understood in relation to a particular piece of writing, and may not make a lot of sense whithout the knowledge of what is being depicted.

Perhaps it would not even all have been so much of a problem if I had “an agent” and a wad of fame – which is, to be honest, mainly the impression I got from my exchange with Le Guin’s representatives. However, I am not a lawyer, and these intricacies go well beyond me. I also have no desire to act in ways that could upset, or damage the interests of an author I admire, and so I will do as I am told.

However this may be: I did not paint these pictures in order to cash in on someone else’s fame, but because I admire the author’s work and felt inspired by it. But even I cannot afford to invest a year and a half of hard work, and then be told that I may not tell people what these images are about, and try to sell them. Wasn’t one of our bloggers recently wondering why there doesn’t seem to be any stand-alone art (as opposed to commissioned illustration) that relates to well known (or even less well known) works of speculative fiction? Well, here is the reason why. I have learned my lesson and turned to other things. And the rest of the series – there were going to be a couple more illustrations for The Farthest Shore, and in particular I was hoping to get round to illustrate some scenes from Tehanu – will now never get painted.

All images on this post are copyright Astrid Nielsch, and may not be reproduced without permission.