This week I’m reviewing a book about the Beatles’ twenty-seven Number One hits in England and USA, by Scott Robinson, called 1/27 (subtitled “A Long and Winding Tour of the #1 Hits of the Beatles”). What? I hear you cry. What the heck do the Beatles have to do with science fiction or fantasy? I’ll answer that question in a moment, but first, let me talk a bit about the book which, short as it is (174 pages, including author page), I found really enjoyable and informative.

This book is specifically about the Beatles’ Number One hits during their long career; whether you like or don’t like the Beatles is immaterial; the fact remains that they were the most influential band in rock history and completely changed the face of popular music forever. During their reasonably short career—they became influential in 1963 and remained the biggest-name band in the entire world until they broke up in 1970. They’ve had more #1 singles than anyone in the world except possibly Elvis and Mariah Carey(!?). While the same song didn’t always chart #1 in both the US and UK at the same time, often they did; this book covers every single that made it to the top of the charts in either/both the US and the UK. (When I—and the author—speak of “singles,” we’re referring to that mainstay of rock’n’roll from the 1950s to the advent of the Compact Disc—the seven-inch 45 r.p.m. record. Younger readers might not be very familiar with them.)

The author, Scott Robinson, has written several books about the Beatles, both as compendiums of trivia (Rock Candy: The Beatles) and quotations (The Quotable Beatles); he’s also written other Beatles books as well as books about ‘80s rock, rock album covers and the band Yes. He’s a journalist and musician, and wrote about music for twenty years for the Louisville Courier-Journal, so he can be presumed to know what he’s talking about. (His musical knowledge, judging from the in-depth information about song construction, exceeds my own by quite a bit.)

The cover of the book (See Figure 1) has been made to somewhat resemble the cover of the CD released in 2000, called #1, a clever bit of marketing. But what about the contents? The songs covered range from their first UK Number One, Love Me Do, to the last record (while they were still Beatles) to hit that top spot, The Long And Winding Road. Of course, even though two of the “Fab Four” have headed off to that great Concert Tour in the Sky—joining such luminaries as Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison (no, I’m not gonna name every dead musician; there are now just too many of them)—as a group they have released new records (I’m using that term interchangeably at this moment for vinyl and CD) many times since the group broke up (including a brand-new collection of monophonic singles released this month); the afore-mentioned #1 remains the fastest-selling album of all time, according to Wikipedia. (Side note to Stephen King fans: I hope John Lennon and George Harrison haven’t gone to that town in the story “You Know They Got a Hell of a Band”!)

So what kinds of things are said about the songs? Each song is, more or less, accorded from three to five pages, interspersed with a page containing a quote from a Beatle or related person. It starts with a little chart detailing who wrote it (mostly Lennon/McCartney, though sometimes Harrison or Lennon or McCartney separately); where it hit Number One (US and/or UK, date it charted that position, and how long it held it); when it was released in the US; when released in the UK, and what was on the “B” side. (For those not familiar with 45-r.p.m. records, I should explain that they always—until the Beatles broke the mold—contained an “A” side, the side that radio played the most, the side that was expected to chart higher, and the side that got the most promotion; and a “B” side, which was considered a lesser work and often was a space filler. As far as I know, the Beatles were the first artists to release a 45 that had two “A” sides.)

Taking their very first Number One as an example (see Figure 3), Love Me Do, we have headings of:

“The Writing” (example: “Paul wrote most of the song in 1958, while skipping school. John contributed the middle eight [bars],” which usually contains a writing ratio (“Paul 0.7, John 0.3”) called a “Dowlding Score” from the book Beatlesongs, by William Dowlding.

There are also sections on:

“The Music,” containing a short musical analysis of each song (example: “Lennon… asked [Delbert] McClinton how to play the [harmonica] part properly. [McClinton’s harmonica part on the Bruce Channel record “Hey, Baby” was a big influence on Lennon’s harmonica for this song.]”)*;

“The Recording,” (example: “The drumming on this song is one of the Beatles’ most convoluted and disputed bits of history.”);

“The Response,” (example: “Capitol would not release the song as a single. [In the US, that is; the Canadian branch of Capitol released the single shown in Figure 3] It was released in the US on another label [Tollie] in 1964, after the eruption of Beatlemania.”);

“What the Beatles Said,” (example: “’Love Me Do was our greatest philosophical song,’ – Paul McCartney”); and, usually, some

“Factoids”: (example: “The word ‘love’ occurs 22 times in the song.”) Much of the material in this book is taken from Robinson’s other Beatle books cited above, by the way.

*(Delbert McClinton, however, poo-poos the idea that he “taught” John Lennon to play harmonica; this YouTube clip captures both McClinton (and Bruce Channel, who played guitar and sang the vocals on Hey, Baby) as well as the Beatles performing Love Me Do live. He says it right at about 2:03, although he also said that Lennon acknowledged his—McClinton’s—harmonica work in about 1970. This is not to invalidate Robinson’s book—I’ve seen that bit of misinformation in a number of places—but I stumbled on this tidbit accidentally. Ah, teh interwebz.)

So what does all this have to do with SF/F? Patience, young Padawan, as somebody or other said, I’m getting to that. (Or, for the Heinleinians among us, “Waiting is.”) The book does not cover any of the dozens (if not scores) of singles released separately by Paul, John, George or Ringo as solo records. Each one of them—even Ringo, arguably the worst singer of the four and the least talented composer, although one of the best drummers in rock—has had major success on his own as a recording artist and/or touring musician fronting his own band. (Lennon with the Plastic Ono Band, for example; McCartney with Wings; Starr with his All-Star Band(s) and Harrison with the Traveling Wilburys all come to mind.) Each one of them is worthy of at least one book like this one, though as of this writing, Robinson hasn’t, that I know of, written them. This one, however, while not as detailed as many of the books that have been written about the Beatles, is the only one specific to their Number One singles and, as such, is worthy of a place on any Beatle fan’s shelf. I hate to sound like a broken record, but this book, and Robinson’s others, are available on Amazon.

Okay, now we come to the connection between Beatles and our genre: what if there had been no Beatles? What if Paul and John had never met on July 7, 1957 at Wootton fête? (That particular fair continues to this very day, by the way.) What if the British Invasion hadn’t happened when it did—if there were no Rolling Stones, Kinks, and so on? Leaving out how that would affect the world at large, what would its effect be on SF/F?

Well, I can say definitively, that there would be no Spider Robinson in SF. No Stardance, no Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon, no Variable Star; indeed, there might be a Father Robinson somewhere back east—depending on where the Vatican might send him—but we would certainly be the poorer for it, whatever the Catholic Church’s view on its gain. (And there might not be a “Coo-coo ca choo, Mrs. Robinson,” coming from Paul Simon, either!)

Look here: for years (more than thirty of ‘em), I’ve played Beatles music (I’m a guitar player and singer, though not a really good guitarist, like he is, or “Tam” Gordy is) at SF conventions with Spider. He’s a bigger Beatlemaniac than I am, and I’m a serious Beatle-lover. (See Figure 4 – Spider’s 60th birthday party; singing A Capella Beatles.)

But the other day I asked Spider what effect, if any, the Beatles had on his life and/or SF career. What he said was this:

“If it weren’t for the Beatles, I might very well be a priest by now. I doubt Father Spider would have been able to get permission from the Society of Mary of Paris (my old order) to write science fiction stories. So: no Beatles, no me.

I was in the seminary, completing my junior and senior years of high school in a single year, when the Beatles came to America. We were allowed to watch TV news every day for fifteen minutes after soccer, and one day, the news was all about four moptops from England. None of their music was played—but my ears grew points, anyway. These guys were unmistakably cool as a moose. (A popular expression then, God knows why.) And as funny as the Marx Brothers.

That weekend my family drove up to the seminary to take me out to dinner, as they were allowed to do once a month. But this month, my sister Mary was a girl with a mission, practically on fire with it. Her mission was to turn me on. I have never satisfactorily thanked her. Every time a Beatle song ended on the car radio, she would switch stations, and invariably find one playing another Beatles song almost at once. They just fried me in my own grease. I did my very best to memorize the entire Top Ten….and ended up with several mutant amalgamations of three or more different Beatles songs running through my head, stuff that I really wish I had been clever enough to sing into a tape recorder—today, they might be worth something, or at least worth remembering.

A month or two later, I left the seminary. I didn’t yet know what it was—I’m not entirely sure I know even now—but it was clear to me that Something Unprecedented Was Going On out there in the real world, and I knew I would never forgive myself if I missed it for something as ordinary as a religious vocation. I was right. Nearly at once, I learned that with four chords and a fake Liverpudlian accent, a man could get laid—or if not, at least be consoled. As a means of directly apprehending God, it beat prayer.

A few years later, I was having the time of my life singing Beatles songs in the lobby of a dormitory when a guy came up and offered to pay me to do that at a campus dinner he was planning. It was my first realization that it was possible to make money doing something you wanted to do anyway. I put myself through the next couple of years of college by playing acoustic, folkie versions of Beatles songs. And then, just as folk music began to vanish from the earth, I had the happy inspiration that perhaps I could also earn money by typing up imitations of my favorite science fiction stories. Soon, instead of earning a pittance by listening to Beatles songs and then figuring out ways to creatively rewrite them, I was earning serious money (by folk music standards) for reading stories by Heinlein, Sturgeon and Pohl, and dreaming up ways to file the serial numbers off the engine block and peddle them in the next state. Turning what you love into a living: for me, it all started with the Beatles.”

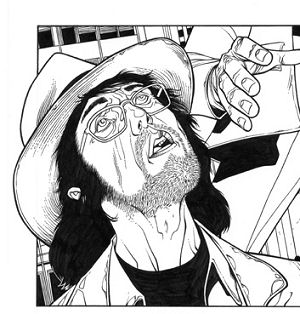

The above is, by the way, copyright ©2014 by Spider Robinson. To further show Spider’s influence on popular culture, here’s a portrait of him from a Marvel comic book: specifically, The Fantastic Four, where artist Steve McNiven shows him (a younger Spider; his hair has a lot of grey in it now), wearing his trademark Panama, gaping up at Mr. Fantastic, who is scaling a building. So without the Beatles our world, the world of SF, would be one heck of a lot poorer! (Marvel®, Fantastic Four®, Mr. Fantastic® are all copyright and trademarked and registered by Marvel Entertainment and/or Walt Disney. No infringement intended; all Marvel® references may be licensed under Creative Commons©.)

Please comment—just say anything!—on this week’s column/blog entry. If you haven’t already registered—it’s free, and just takes a moment—go ahead and register/comment here; or comment on my Facebook page, or in the several Facebook groups where I publish a link to this column. I might not agree with your comments, but they’re all welcome, and don’t feel you have to agree with me to post a comment; my opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owners, editors, publishers or other bloggers. See you next week!

When I saw Spider reading at the H. R. MacMillan Space Centre I first learned of his love for music and the guitar. Shortly after that I took up guitar (again) as well as singing. As I began performing for others the connections I made between storytelling and song grew stronger. Knowing this, I’m more pleased than surprised that the Beatles were inspiration to write.

Thank you for posting this. Spider singing the Beatles is amazing. It’s hard to imagine a world where that didn’t exist.