I am not reviewing the 1954 Disney film, but a version filmed in the Bahamas 38 years earlier by writer/director Stuart Paton. The opening title card declares “The first submarine photoplay ever filmed.” The underwater scenes are genuine. In 1916? How could this be?

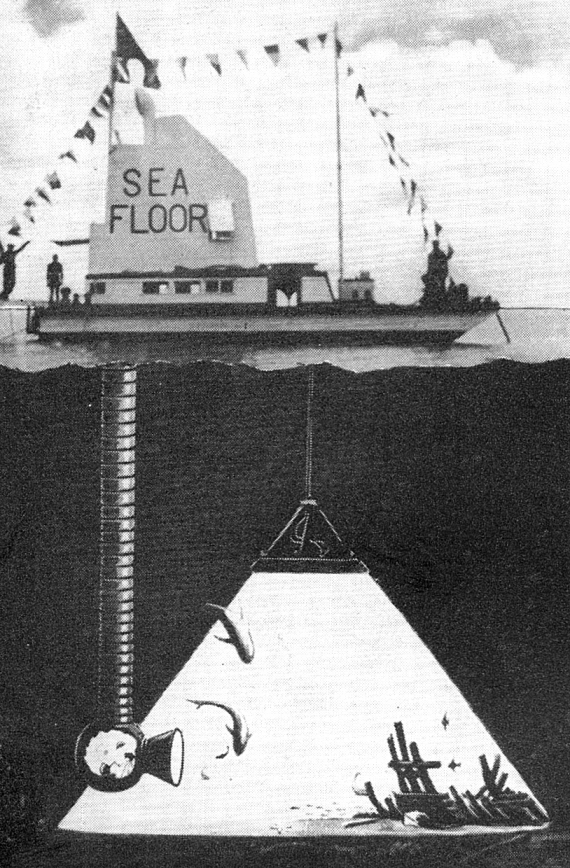

The next card reveals all. “This film was made possible by the Williamson brothers who alone have solved the secret of under-the-ocean photography.”

We see a shot of brothers George and Ernest, rather nattily dressed, doffing their hats to the camera. Their secret was the ‘photosphere’, a simple and rather obvious device for letting a camera crew shoot 30 or 40 feet beneath the surface.

The film begins with Professor Aronnax receiving a letter from the U/S. government inviting him to join an expedition to hunt a monster which has been sinking ships. On board the warship Abraham Lincoln he meets Ned Land, a harpoon expert. They strut about the ship admiring the rigging, as if they’d never seen a ship before.

We are introduced to Nemo via a shot showing him puffing a long pipe as he stares fixedly into the camera. Because of his white beard and piping-lined costume, he rather disconcertingly resembles a thin Santa Claus, a vision hard to shake throughout the entire film. Allen Hollubar, the actor portraying Nemo, is wearing blackface because Nemo is, after all, East Indian, a fact left out of the Disney version.

We see the Nautilus underwater, a rather bouncy blimp shape covered in shiny riveted plates with diving planes fore and aft and a single motionless propeller in front of the rudder. This is, of course, a model.

When we observe the sub on the surface we are looking at a 100 foot long motorized movie prop that moves about on its own. A narrow catwalk gives way to ballast tanks bulging down to the waterline on either side, the only visible features being a tiny housing for the pilot to peer through, and behind that a periscope. Overall the sub presents a surprisingly modern appearance.

The Nautilus confronts the Abraham Lincoln. There is a dramatic shot of Ned Land and others clutching the railing and staring in horror at the Nautilus as it cuts across their bow. Ned hurls his harpoon.

“Its hide is too tough for harpoons!” shouts Ned.

Only an idiot would think this metal marvel covered in rivets could be a living creature, but everyone goes on ignoring the evidence of their own eyes. We see the sub cut close to the stern and are told (not shown) that the Professor and his party are hurled into the water by the impact. The rudderless ship drifts away, and Nemo decides to rescue the swimmers.

Meanwhile a Lieutenant Bond and four Union troopers escape from somewhere in a balloon. Days later they float over a “Mysterious Island” where a “child of nature” lives. The actress June Gail is depicted wearing a leopard skin which reveals about 99% of her legs, more than amply demonstrating she is also covered in blackface. (Gosh, who could she be related to?) She has very long hair and is much given to prancing about like Isadora Duncan. Rather fetching, she is.

The lithe young woman watches the balloon crash in the ocean and finds it all very amusing, but then, she finds everything amusing.

Meanwhile the Nautilus just happens to be cruising offshore just beneath the surface. Nemo looks out from his cabin’s large crystal window and gasps. Cut to a shot of an unconscious man floating AS SEEN FROM BELOW. This view must have knocked audiences off their seats as something truly incredible.

Nemo orders two of his crew to dive in and take the man ashore. They leave him in a cave at water’s edge. Leaping back into the surf surging around rocks was undoubtedly dangerous, but these were professional Navy divers the director had hired. All the same, they were risking their lives.

Next, another wonderful shot. The girl is dancing with her arms outstretched on a hilltop surrounded by hundreds of birds whirling about her. Beautiful.

Then she watches the now-united castaways (they found the missing man in the cave) discover a raft bearing a sea-chest full of goodies which Nemo thoughtfully let drift ashore.

“I call this my magic window,” says Nemo, letting Ned and the Professor view the ocean’s wonders from a huge port hole in his cabin. We are treated to seemingly endless shots of marine plants and coral sprouting from the sea floor. Boring now, but back in 1916 literally the first time an audience had ever seen film footage of underwater life. Shots of barracuda and sharks swimming about must have stunned contemporary viewers.

Back on the island, Bond pulls the girl out of a pit he dug to trap wild animals. She fights at first, but by the time he’s brought her down to the beach she’s very coy. He brings her clothes, then introduces her to the others. A chap we know to be a villain—because he’s bearded—gets a thoughtful look on his face. The girl takes Bond back to her hut and tries to pull him in. Always a gentleman, he backs away and leaves. Then we see the villain creeping toward the hut.

Onboard the Nautilus, we witness Captain Nemo showing his guests how to don diving suits which resemble conventional hard helmet outfits but are lacking in hoses leading to a surface pump.

“With our supply of oxygen, we can remain underwater indefinitely,” says Nemo. He exaggerates.

In fact these suits incorporated the “Davis Submarine Escape Lung,” a rather dangerous rebreathing device which uses the chemical Oxylithe to purify a diver’s breath. Notoriously its fumes affect divers, causing them to wander off picking sea anemones, or starting fights with one another. This film production was lucky, there were no serious accidents.

The audience is treated to authentic shots of divers walking the ocean floor. The air in their suits ballooned the fabric around their shoulders and chests, causing them to resemble the spindly-legged big-lunged Martians beloved of pulp fiction.

We see sharks. Then divers and sharks together. Divers kick upwards like gigantic frogs to fire compressed air guns at the sharks passing overhead. In one especially eerie shot a shark emerges head-on from the murky distance to swim languidly straight at a diver standing directly in front of the camera, a scene which must have given many a viewer nightmares. At the last moment the diver pokes the shark with the tip of his gun and it turns away. The divers then return to the Nautilus.

Now we meet Charles Denver, a sea-trader haunted by memories of trying to ravish the wife of Prince Daakar, an East Indian potentate. She accidently stabs herself to death, so he kidnaps her young daughter instead, later leaving her on the “Mysterious Island.”

Obviously the “child of nature” is Nemo’s daughter. Denver decides to search for her, and arrives at the island in his yacht. Dressed for the tropics in a velvet coat and Deerstalker hat, he wanders through the jungle alone. He gets lost and goes mad, the actor really chewing the scenery as he employs the blind staggers and other choice bits of overacting.

Cut to the Nautilus. Nemo is brooding before his giant portal again. He sees a native dive from a small boat to kick about the bottom in search of pearls. Turns out a giant Octopus is sitting upright on the coral. The diver plays ye old trick of wrapping himself in the tentacles and jerking about to indicate a struggle.

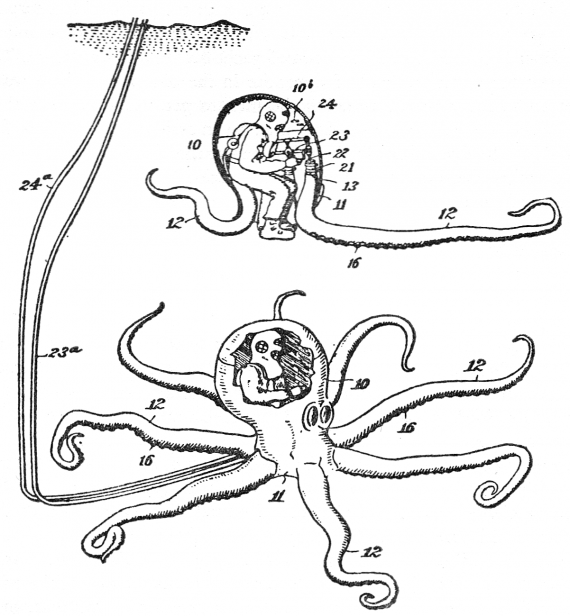

Since the somewhat murky scene was actually filmed on location in Nassau the Octopus appeared to the credulous audience of the era absolutely authentic, so much so that the actor John Barrymore, on seeing the film, told Ernest Williamson that he “had never been so thrilled.” The Octopus was U.S. patent No. 1,378,641, a rubber gizmo with coiled springs inside the tentacles which were controlled by a diver within the body. It is a great monster.

Oddly, Bond asks the girl if she remembers her mother. She tells him about her mother’s murder, about Denver, and so on. All of a sudden she knows English? And what happened to old lusty-beard moving toward her hut? Well, Bond leaves, and now we see the same shot as before of the villain approaching the hut. Little bit of a continuity problem here. He sneaks in, tries to kiss her. Bond comes a-running, and after a bout of fisticuffs “the scoundrel is made an outcast.”

Meanwhile, Charles Denver is still lost.

Nemo discovers Denver’s yacht, sends two men ashore to find out who it belongs to. For some odd reason, rather than swim in, they don diving suits and walk to shore. The shot of them emerging from the surf must have struck 1916 audiences as amazing, if not surreal.

Sailors from the yacht find the villain, who claims to be alone. They tell him about Denver while the two crewmen from the sub listen in. The villain finds Denver and they are taken to the yacht. There old lusty-beard plots to get control of the yacht and steal the girl from the island. He convinces two sailors to help him, and they row him back to shore. Only now do we see the two Nautilus crewmen walking back into the surf. Either they’ve been goofing off, or it is another editing/continuity problem.

Events occur fast and furious. The girl is transported to the yacht. The hero swims after her. The Nautilus crew members report to Nemo, who orders a torpedo loaded. The villain fights Denver. Bond fights the villain. A torpedo is fired. Bond and the girl leap into the water. Denver and the villain fight. The yacht blows up, burns, and sinks.

The day the explosion was filmed the Governor of the Bahamas happened to visit the set with his wife and official party in his personal yacht. A miscue resulted in the fuse to the explosives aboard the movie’s yacht being lit while the Governor’s boat was still tied along-side. The Governor ignored all warning shouts so the director simply shrugged and ordered the camera to roll. Fortunately for the film the Governor’s vessel wasn’t in the frame when the yacht exploded. Fortunately for the Governor he came through the explosion unscathed, and promptly fled. So much for Anglo-Yank relations.

Nemo is reunited with his daughter and promptly dies. Well, not exactly promptly, as first there’s a long flashback about Charles Denver falsely accusing him of fomenting revolt against colonial authorities. After a few spectacular battle scenes involving a hundred or more costumed extras, Nemo—as Prince Daakar—swears vengeance. How he happens to invent the Nautilus and convince an exclusively all-Caucasian crew to serve him goes unexplained. Then Nemo collapses and dies. From what? Happiness I suppose.

There follows the moving scene of his underwater funeral.

The final shot: the sun peeking from behind the girl’s profile as she stands with Bond on the deck of a ship leaving the island in a scene titled “The Benediction.”

The film is surprisingly effective, despite its age. The underwater shots and view of the Nautilus on the surface are quite nifty, the cinematography occasionally superb, and the acting style, once you get used to it, loads of fun. It bears up well in comparison with the Disney version, and in some ways, oddly enough, is more convincing.

Sources:

TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA – 1916 (Film).

MAN UNDER THE SEA – James Dugan, 1956, Harper Brothers (Book).

TAKE ME UNDER THE SEA: THE DREAM MERCHANTS OF THE DEEP – Thomas N. Burges, 1994, Ocean Archives (Book).