I attended a lecture on Ancient Mayan politics for another reason, but as I was jotting notes and listening to the power and culture unfold in my mind’s eye, it struck me that this particular polity would be a fascinating way to create a turn-key world in a fantasy or science-fiction story. Because it is a little-known and very non-Western culture, it will give a feeling of exotic other-worldliness to a story, without having to make it up as you go, useful for maintaining consistency in world construction. I will be seeking out more information on obscure cultures such as this one, to lend my own writing a new and different flavor. What is old, become new.

I attended a lecture on Ancient Mayan politics for another reason, but as I was jotting notes and listening to the power and culture unfold in my mind’s eye, it struck me that this particular polity would be a fascinating way to create a turn-key world in a fantasy or science-fiction story. Because it is a little-known and very non-Western culture, it will give a feeling of exotic other-worldliness to a story, without having to make it up as you go, useful for maintaining consistency in world construction. I will be seeking out more information on obscure cultures such as this one, to lend my own writing a new and different flavor. What is old, become new.

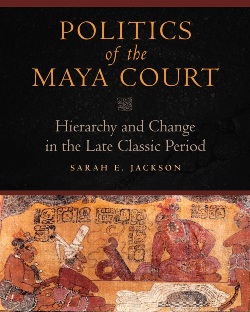

Sarah E. Jackson, a professor at the University of Cincinnati, lectured at the Latin American Culture Fest on Saturday. Her topic, Ancient Mayan Politics: The Royal Court, Its Members, and How they Transformed Classic Period Governance. Spelling mistakes in the notes are mine, she was not always projecting the words she used.

Using stone monuments and their hieroglyphs as supporting evidence, she asks, “What was the nature of the classic Royal Mayan court?” She advocates moving away from the idea of one central figure into the concept of many figures of power. Through the interpretation of hieroglyphs, her attention will thus focus on visual and textual evidence. Each Mayan polity was an independent city-state with a ruler, the Kukla-Ko (sp).

•Dumbarton Oaks Panel•

•Piedras Negra Panel 3•

•Site R Lintel 1•

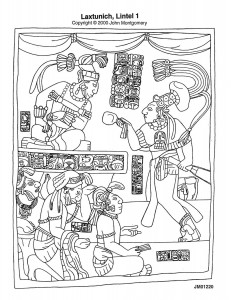

•Laxtunich Lintel 4•

•Piedras Negra Panel 3•

This panel was “deactivated” or intentionally defaced in ancient times. It remains a very naturalistic depiction. A ruler in an architecturally framed space, and a very crowded place with a swirl of people around the ruler. He is elevated on an ornate throne, but leaning forward from a cross-legged position and engaging with the multiple people of his court. People standing on his right are family, and on the left are visitors from a neighboring city. The seated people are his court, labeled with little glyphs. Some are named, and some have titles, including baah ajaw, anab, sajal, baah sajal, and one says, directly addressed to the ruler, “a-wink-en” (I am your servant).

There are five known titles that describe members of the Mayan Court.

Sajal

Ajk’uhuun

ti’uhuun/ti’sakhuun (at the mouth)

banded bird (no known phonetic translation)

yajaw k’ahk

Contextually, loooking at the uses of these titles gives us an idea of their roles. All five positions are associated with accession. For instance:

chun “seating”

joy “encirclement”

k’ah huun “headband tying”

The titles are a Late Classic phenomenon, arising sometime between 600-900 AD, which correlates with a transitional time. A main river area is likely where the courtly accession traditions were born.

The positions within the court are distinctive within each polity. They are a group structured in specific ways, acting as shared building blocks of Mayan Political community.

•Site R Lintel 1•

The emphasis is on a particular individual, Ahk’mool (sp), who showed how variable and adaptable the nature of the court was, as seen through the movements of a specific persona. He is shown dancing in this image, the same size as the ruler. He is labeled a sajal, the owner of four captives, and as chook (young, unripe). He may have acted as an overseer, or a local ruler. Because Ahk’mool shows up on several sites, we are able to trace his political trajectory. He served under two rulers, with a ten-year interregnum period. His story demonstrates the importance of court members providing stability during a tumultuous time. On Lintel 4 he is labeled and ak’huun, having elevated in status, but on Lintel 3 he is listed with no status title.

•Dumbarton Oaks Panel•

Variety in structure and organization in the court shows flexibility. The panel shows Chac’tuun (sp), who is eventually a sajal as his father was a sajal. His position is related to shifts in his family. He was not seated as sajal until his father died when Chac’tuun was forty-eight. We see the processes of change at a personal level.

•Tonina Monument 165•

This source shows us that Koni’nish (sp), an individual at Tonina, held more than one office simultaneously. Different locations of courts might have from one to five types of courtiers. Reasons might be dictated by local needs and resources. So we see that we have a culturally anchored institution that is capable of adapting to local needs.

How They Themselves Understood the Court

At Laxtunich we are able to begin accessing Mayan Metaphors for framing the court. Here, labeled individuals are supporting the ruler. The are labeled as powatuuns (sp) who are otherworldly figures who hold up the sky in Mayan Myths. Courtiers are parallels in their support of rulers to the powatuun (sp). Earthly courts are depicted similarly to Heavenly courts on these monuments.

Kelen Hix on the Tonina Monument 165 belongs to the paddler gods: he is possessed by them. This possession conceit is associated with rulers, and it is interesting to see that a courtier could also have access to the gods. Sources of power, it is suggested, were, sometimes not the sole provenance of the ruler. It provides a divine mandate to the framing of the royal power, in that divine relationships were not solely the milieu of the ruler.

An agricultural metaphor frames courtiers as plants and farmers. We saw the use before of ch’ok, which means young, junior, but literally, green or unripe (in connection with Ahk’mool). Pakal’s sarcophagus found at Palenque, shows courtiers drawing sustenance from the body of the ruler, their own bodies sprouting from the surface of the earth and growing leaves. They were u chun thanob: procipals of a village, literally the roots of power.

The work of the court is described as farming. Chub: overseeing, but also literally to plw, from the Palenque tablet of the slaves. In a larger sense, this represents the importance of agriculture in every level of Mayan Society. Elite roles are integral to the representations, as they were a critical part of the court.

So we have a recognition of the constituent components of the court: a transformation of our conceptions of Maya governance. The structure of the court is far from being stagnant or static. Flexible organization allowed for active management. And by accessing Maya conceptions of their court through twinned metaphors of divinity and agriculture, we grasp an understanding of how they perceived themselves.

Recent Comments