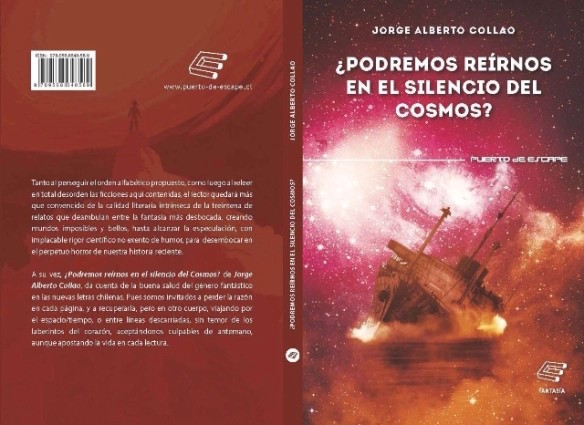

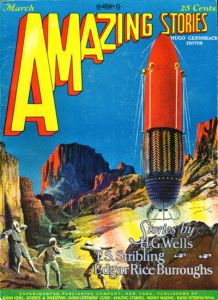

A group of explorers react with shock and awe to an enormous red vessel, located seemingly in the middle of nowhere. At first glance, a modern observer might take the vehicle for a rocket; contemporary readers, on the other hand, would have recognised it as an upright Zeppelin.

A group of explorers react with shock and awe to an enormous red vessel, located seemingly in the middle of nowhere. At first glance, a modern observer might take the vehicle for a rocket; contemporary readers, on the other hand, would have recognised it as an upright Zeppelin.

It was March 1927, and Amazing Stories was concluding its first twelve-issue volume.

Hugo Gernsback begins his editorial by announcing that the magazine has switched to a cheaper, thinner paper, and that the original stock (dubbed “Amazing Stories Bulky Weave”) has been discontinued. After this, he goes onto discuss a conundrum he faces when editing the magazine: stories that prompt high praise from half of the readership, and strong derision from the other half.

“If you, dear reader, were the editor,” he asks, “what would your reaction be to such a condition… Would you hesitate about the next story before publishing it, or would you simply throw yourself to the fishes and simultaneously throw up the sponge?” He concludes by stressing that Amazing Stories is the first magazine of its kind, and sometimes running contentious material is an inevitable part of exploring new publishing territory.

So, let us take a closer look at the sponges thrown up in the March 1927 Amazing Stories…

“The Green Splotches” by T. S. Stribling

In this story reprinted from a 1920 edition of Adventure magazine, a trio of explorers – engineer Pethwick, linguist Demetrovich and secretary Standifer – head out to a region of Peru. Their destination is so inhospitable that the only guides they can convince to come with them, Ruano and Pasca, are convicted felons on death row.

In this story reprinted from a 1920 edition of Adventure magazine, a trio of explorers – engineer Pethwick, linguist Demetrovich and secretary Standifer – head out to a region of Peru. Their destination is so inhospitable that the only guides they can convince to come with them, Ruano and Pasca, are convicted felons on death row.

The travellers encounter a number of strange sights, including unexplained lights in the distance and a row of animal skeletons hung up in evolutionary order, with human bones at the very end. Ruano vanishes, last glimpsed chasing another person; the only hint of his fate is a set of green splotches on nearby rocks, which turn out to be chlorophyll stains. Standifer meets a native – who bears a resemblance to the missing Ruano – and trades a book for gold, only to suffer health problems shortly afterwards, as though the gold is poisoned.

Speaking to this native, the explorers clear up some of the mysteries. They learn that the strange lights were portable furnaces, that the bones were arranged merely to scare intruders and dangerous animals, and that radium is plentiful in the area – explaining the contaminated gold. The man also reveals that he is from a technologically advanced society where people are identified by number, rather than name; his number is 1753-12,657,109-654-3, although the explorers dub him Mr. Three for short.

However, things are set to get stranger still. It turns out that the reason Mr. Three resembles Ruano is that he is, in fact, wearing Ruano’s flayed skin.

Three, armed with a rod that focuses electricity, captures the explorers and takes them back to his homeland, which bares the similarly numeric name of One. The men disagree amongst themselves as to where One’s yellow-skinned, large-headed inhabitants originate: are they descendants of Incas, or some sort of Bolshevik colony? Another theory is that they are aliens – a theory all but confirmed when, during a scuffle, the explorers learn that the yellow people bleed green blood containing chlorophyll. Which also explains those green splotches…

What starts out as a straightforward lost civilisation story, with typically dated racial politics, ends up as an exploration of extra-terrestrial biology. The adventure of the travellers ends rather abruptly, and gives way to a long epilogue where a character (not involved in the preceding story) goes over the events and offers his theories about the nature of the aliens, concluding that they are sapient plants from Jupiter.

“Under the Knife” by H. G. Wells

This issue’s H. G. Wells story is a weird tale from 1896. The main character is a man due to undergo an operation; he becomes convinced that he will die during surgery; but views his impending demise with emotionless detachment. Much of the story’s opening is spent establishing the protagonist’s apathetic nature.

This issue’s H. G. Wells story is a weird tale from 1896. The main character is a man due to undergo an operation; he becomes convinced that he will die during surgery; but views his impending demise with emotionless detachment. Much of the story’s opening is spent establishing the protagonist’s apathetic nature.

During the operation, the unconscious man somehow becomes acutely aware of his surroundings. Not only does he see the surgery taking place on his body, he can read the minds of the surgeons. After a mishap in the operating theatre, the man’s consciousness flies into the skies above London. He soars further and further, leaving Earth’s atmosphere and exploring the solar system. Eventually, he sees the whole of the universe from afar: just one spot of light on a glittering ring… a ring worn by a hand of unfathomable proportions.

But the operation turns out to be a success, and the man’s mind is returned to his body.

With its cosmic scope, this relatively little-known Wells story has similarities to Edgar Allan Poe’s “Mesmeric Revelation”, published twenty-two years earlier and reprinted in the May 1926 Amazing. It also prefigures some of the themes later explored by Olaf Stapledon and David Lindsay.

“The Hammering Man” by William B. MacHarg and Edwin Balmer

Another adventure of scientific detective Luther Trant, who by now had become a regular character in Amazing. This time, Trant gets a visit from one Winton Edwards, whose lover Eva has suddenly and inexplicably abandoned him. Winton believes that Eva has fallen under the influence of a strange man, known for his habit of deliberately hammering on the walls of a corridor with his fists.

Another adventure of scientific detective Luther Trant, who by now had become a regular character in Amazing. This time, Trant gets a visit from one Winton Edwards, whose lover Eva has suddenly and inexplicably abandoned him. Winton believes that Eva has fallen under the influence of a strange man, known for his habit of deliberately hammering on the walls of a corridor with his fists.

The detective tracks down the hammering man, who turns out to be a Russian named Meyan. He also speaks to Eva, and finds that her family history is knee-deep in Russian political intrigue. Measuring Meyan’s pulse with a device called a sphygmograph, so as to gauge his emotional state, Trant exposes the truth: Meyan is actually a member of the Russian secret police who had been posing as a revolutionary. The mysterious hammering, Trant goes on to explain, was the spy’s method of sending coded messages.

Once again, this is a routine detective yarn given modest SF interest by the usage of a mechanical device during the interrogation scene.

“Advanced Chemistry” by Jack G. Huekels

In this reprint from Gernsback’s Science and Invention magazine, Professor Carbonic has developed a method of raising the dead by injecting them with a fluid. He first resurrects a dead rat, then heals a badly-injured girl, and finally moves on to reviving dead people. He explains that human movements are motivated by electricity, and that his fluid solution acts in the same way as the fluid of an electrical battery. At the height of his success he suffers a heart attack; an onlooker tries to revive him using his own methods, but botches the solution. Carbonic comes back from the dead over-charged, giving off sparks and fatally electrocuting both himself and the man he had just revived.

In this reprint from Gernsback’s Science and Invention magazine, Professor Carbonic has developed a method of raising the dead by injecting them with a fluid. He first resurrects a dead rat, then heals a badly-injured girl, and finally moves on to reviving dead people. He explains that human movements are motivated by electricity, and that his fluid solution acts in the same way as the fluid of an electrical battery. At the height of his success he suffers a heart attack; an onlooker tries to revive him using his own methods, but botches the solution. Carbonic comes back from the dead over-charged, giving off sparks and fatally electrocuting both himself and the man he had just revived.

A tongue-in-cheek story (Carbonic’s supporting cast includes such individuals as Mag Nesia, Sal Soda and Doctor X. Ray), “Advanced Chemistry” fits into the tradition of short, humorous stories about wacky invnetors that had already been established in Amazing. It is not one of the better examples of its type.

“The People of the Pit” by A. Merritt

A group of travellers arrive at a cluster of mountains said by the local natives to be cursed. There, they first see weird lights in the sky, and then encounter an unknown being that turns out to be a man crawling on all fours. Examining him, they find that he has been crawling for so long that his hands are twisted into worn-down stumps; even when he falls asleep, his body continues to move in a crawling motion.

A group of travellers arrive at a cluster of mountains said by the local natives to be cursed. There, they first see weird lights in the sky, and then encounter an unknown being that turns out to be a man crawling on all fours. Examining him, they find that he has been crawling for so long that his hands are twisted into worn-down stumps; even when he falls asleep, his body continues to move in a crawling motion.

When awake, the man speaks of “The people of the pit… Things some god of evil made before the Flood”. Giving his name as Sinclair Stanton, he outlines his harrowing tale…

Stanton relates how he had visited the mountains in search of gold, and found a vast pit. There, he came across carved images and text (resembling Chinese, but actually “made by hands, dust ages before the Chinese stirred in the womb of time”). Descending further, he found a weird subterranean city, and still more carvings – ones so bizarre that he is unable to describe them.

Next, he encountered floating lights, and felt the lashes of unseen whips. Falling unconscious, he came to to find himself chained to an alter. By gradually grinding away at the chain he was able to escape, pursued by the lights – which, it turned out, were attached to floating slug-like beings. Through sheer will he was able to crawl out of the pit, his limbs mutilated and his head filled with weird images. He dies shortly after recounting this story, and his discoverers cremate him… at which point his ashes blow back into the pit.

Originally published in All-Story in 1918, this tale has similarities to Merritt’s novel The Moon Pool, which began serialisation the same year and also uses the central image of mysterious lights in a subterranean city. But while The Moon Pool is an adventure story, “The People of the Pit” is a horror story of the Lovecraftian variety. The motifs of unseen horrors, indescribable images and incomprehensible history are all ones that H. P. Lovecraft would utilise in his own work, which was beginning to blossom around the time “The People of the Pit” was published.

The Land that Time Forgot by Edgar Rice Burroughs (part 2 of 3)

Still trapped in Caspak, a remote island populated by prehistoric throwbacks, the hero Bowen Tyler goes looking for his lover Lys. He encounters cavepeople at various levels of intellectual development, and eventually finds Lys in the clutches of a particularly nasty brute. After he rescues her, the two conclude that they have no hope of leaving the island – but they will at least be able to live out their days with each other.

Still trapped in Caspak, a remote island populated by prehistoric throwbacks, the hero Bowen Tyler goes looking for his lover Lys. He encounters cavepeople at various levels of intellectual development, and eventually finds Lys in the clutches of a particularly nasty brute. After he rescues her, the two conclude that they have no hope of leaving the island – but they will at least be able to live out their days with each other.

So ends The Land that Time Forgot. The conclusion is immediately followed by the sequel, The People that Time Forgot.

After Bowen’s message-in-a-bottle account of his adventures reaches America, a search party heads off to find him. One member of the group, Bowen’s friend Tom Billings, splits off from the rest and has adventures of his own in the savage land.

As the title suggests, the various cavepeople get a larger role in Tom’s story than they did in Bowen’s. The groupings include the Alus, who are incapable of speech and scarcely more than apes; the hirsute Wieroos, who are entirely male and so must abduct females from other groups to survive; and the Galus, whose society represents the highest form of civilisation on the island. In a strange twist, Tom learns that a native of Caspak will undergo a process of evolution during his or her lifetime, developing from an ape-like Alu to a higher being such as a Galu and migrating to that group’s territory.

During his adventures Tom falls in love with Ajor, daughter of the Galu chief. This gender-reversed Tarzan and Jane scenario is something that Burroughs had already explored in his earlier story The Eternal Lover.

Discussions

“The Moon Hoax”, published back in September, is a recurring topic in this month’s letters column. Howard Bowman dismisses the article as a “rotten” piece of work with no place in a scientifiction magazine. Sixteen-year-old Edgar Evia appears to have been more amused by it, and submits a brief mention of the hoax from the October 1835 American Review. Meanwhile, Antonio G. O. Gelineau defends Amazing’s publication of “The Moon Hoax”, and goes on to praise the humorous Dr. Fosdick stories (“Fosdick’s electroplating story hit me so hard that I immediately coated rats with graphite and plated them with copper”).

Herbert H. Smith vouches for the entomological accuracy of H. G. Wells’ “The Empire of the Ants”. F.B.K. lauds “The Man Who Could Vanish”, and connects this tale of invisibility to a personal account of a spider and its web seemingly vanishing into thin air. On a less positive note, Wesley A. Kauder questions whether six miles of water could really recede beneath the Earth’s crust as depicted in The Second Deluge, while S. W. Ellis launches an all-out attack on the stories of A. Hyatt Verrill. “Why should people, developed to such an extent in mental telepathy need ears like a hunting dog?” he writes of “Beyond the Pole”. “Why should Dr. Unsinn declare that he does not intend to produce invisibility by causing ab od to permit light rays passing through it? How in the world can invisibility otherwise be produced?” he asks in response to “The Man Who Could Vanish”. “Why should a civilized people, such as those in ‘Through the Crater’s Rim,’ walk on their hands and their feet when animals such as rats, squirrels, kangaroos etc., know enough to use the members nearest their head and eyes?”

Oh well, you can’t please everyone…