(Previous parts of this column can be found here: Part 1: Part 2: Part 3:)

Before we get started, may I ask if you’re excited about the news that Fox Mulder and Dana Scully, FBI agents, will be back with us this year? Everyone has surely heard by now that 6 new episodes of The X-Files have been ordered, starring David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson as Mulder and Scully. I confess I have mixed feelings; while we watched the show every week, they were up and down a lot; sometimes the “monster of the week” can get a little tiring. Then the writers get all “jump the shark” and we end up with stuff like The X-Files: I Want To Believe, a movie that made almost no sense whatsoever. (Before that, even, with all the alien baby stuff.) On the personal side, my friend William Gibson wrote a couple of episodes with his longtime friend Tom Maddox, which added to the fun. Then there’s Supernatural, which we (I and my wife, the Lovely and Talented Lynne Taylor Fahnestalk) confess to watching almost as devotedly, except they jumped the shark when they started all this “Angels and Demons” stuff. Fortunately, they’re more or less back to “monster of the week,” which was much more inventive and fun. (And yes, before you say anything, I do like the character of Castiel, and Crowley’s mom is kinda fun too.) And of course, both shows were/are filmed locally, which means we can have fun pointing at the screen and saying “Minnesota? No way, that’s Langley, BC!” and stuff like that there. I myself watched part of an episode of Supernatural being filmed only a few blocks from here (my home), where Dean and Sam went into a building and came out repeatedly, before jumping into their car and driving off with that particular “muscle car” throaty burble. Here’s a shot of that classic Impala I took from across the street (the film people told me we’re not allowed to take photos, so don’t tell anyone about this picture, okay?)

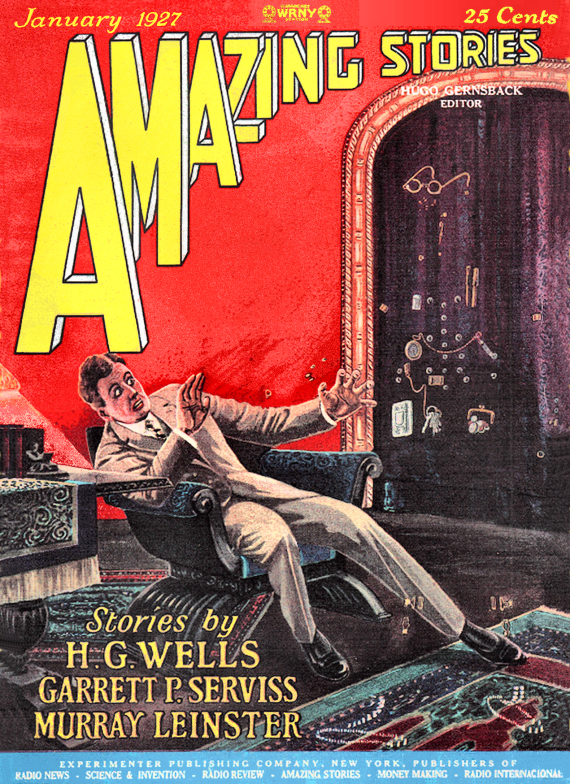

Anyway, back to Amazing’s first year. I had a bad copy of the cover of this issue (Volume 1, Number 10, January 1927); I looked all over the internet to find one I could make even this good, but in spite of all my work, it still looked dodgy. Since I don’t have the actual magazines—I bought a DVD some years ago with most of the early Amazings scanned onto it—when the scanned cover looks bad I search the internet carefully for another cover or covers that I can use to either fix or recreate a better cover. My editor, however, had a high-res one, which he substituted for my edited cover. So Steve Davidson deserves kudos for this particular cover. Here are the contents of the first issue of 1927:

Amazing Stories Vol. 1 No. 10 (January 1927) Contents:

- “Incredible Facts”—Editorial by Hugo Gernsback

- “The Red Dust”—novelette by Murray Leinster (sequel to Mad Planet)

- “The Man Who Could Vanish”—novelette by A. Hyatt Verrill

- “The First Men in the Moon”—serial (Part 2 of 3)—by H. G. Wells

- “The Man with the Strange Head”—story by Miles J. Breuer, M.D.

- The Second Deluge— serial (Part 3 of 4) by Garrett P. Serviss

- “Discussions” (Lettercol) with answers by the editor

Cover by Frank R. Paul illustrating “The Man Who Could Vanish”

The “Incredible Facts” here contains an item I still find incredible: Gernsback alleges that scientists in Dutch Guiyana (now just Guyana) verified that some native “witch doctors” ground the heads and tails of rattlesnakes (”…the most deadly one imaginable…”) and mixed them with certain herbs, then put this mixture into the veins of men who from then on had the “power of paralyzing snakes” so that when one of these people approached a snake, no matter how deadly, it became “powerless”! How’s that for scientific fact, folks? Then there’s the story of Kaspar Hauser, who modern readers may not be familiar with, but readers of Charles Fort will be. The stories in this issue are a mixed bag: “The Red Dust” just continues the story started by Leinster in his “Mad Planet”; the Verrill story is just a riff (supposedly a bit more scientifically presented) on Wells’s own The Invisible Man; The First Men in the Moon continues the story of Cavor and the Selenites—proving that the Ray Harryhausen version was actually somewhat faithful to the book! (I hadn’t actually read it before); the “Second Deluge” is, in its own way, an Earthly version of When Worlds Collide, and “The Man With the Strange Head”’s ending will be familiar to moviegoers who’ve seen Men in Black or Eddie Murphy’s Dave movie. (I can’t say too much; you know how I feel about spoilers.) The lettercol offers a few diversions to modern readers, too: a man takes “The Second Deluge” as real and asks to be sent “plans for a smaller Ark so he can save his family”; another reader disses Jules Verne—finds him too dry and unexciting—but praises Amazing nonetheless. The usual lettercol mixed bag, although Gernsback promises a personal answer to anyone who’ll enclose a quarter to take care of postage and time spent.

And the contents of the February issue (Volume 1, Number 11) are:

Amazing Stories Vol. 1 No. 11 (February 1927) Contents:

- “Interplanetary Travel”—Editorial by Hugo Gernsback

- “The Land That Time Forgot”—(©1918) serial (Part 1 of 3) by Edgar Rice Burroughs

- “On the Martian Way”—(©1907) story by “Captain H. G. Bishop, USA”

- “The First Men in the Moon”—serial (Part 3 of 3) by H. G. Wells

- “New Stomachs For Old”—story by W. Alexander

- “The Eleventh Hour”—(©1910) story by William B. MacHarg and Edwin Balmer

- “The Thought Machine”—story by Ammianus Macellinus

- “The Red Dust a Fact!”—essay with a photo of an exploding mushroom

- “H.G. Wells, a Hell of a Good Fellow – Declares His Son”—interview by H. G. Robison of Wells’s son, Frank Wells

- “The Second Deluge”—serial (Part 4 of 4) by Garrett P. Serviss

- “Discussions” (Lettercol) with answers by the editor

Cover by Frank R. Paul illustrating “The Land That Time Forgot”

If you will recall my previous columns on the earliest Amazings, I notated which stories I found to be reprints and which were originals. The ones I list with early copyright dates are the only reprints that I’m aware of. I didn’t do as thorough a job checking out the stories this time—due to time constraints—because that does take a fairly long time. Even the interwebz have their limitations. Can you imagine how easy research will be in the future, when the Internet of Things is fully realized and practically all the information in the world is online? (Realistically speaking, however, all that research will be costly; people have a habit of charging “all the traffic will bear” for any information they think is valuable.)

To continue with Number 11, we lead off with a Gernsback editorial in which he examines all the known methods of interplanetary travel. He rightly says that antigravity is a bust; if we don’t know (and we’re still not quite there) what gravity is, how can we make “anti-“ it? Then he examines Verne’s giant cannon (From the Earth to the Moon) and correctly dismisses it as a mechanism for shooting people—unless you want a “people paste” arriving (my words, not his)—to the moon; finally he says, again quite rightly, that Goddard’s work with rocketry will provide the way to travel to the nearer planets. And so it is. “The Land That Time Forgot” will be familiar to many moviegoers, as they’ve made at least one movie version—as a “lost world” story; this one framed by a World War I conflict and a German U-boat, but replete with dinosaurs and ape-men. A fun yarn, even if more fictional than “scienti-al.” The Bishop story isn’t similar to, but reminds me of, Tom Godwin’s “The Cold Equations,” in which a sacrifice is needed to save a trapped space-liner. Dryly written, with much less emotion than the Godwin story. “First Men in the Moon” is almost as much fun as the movie version; I can quite see Lionel Jeffries emoting in my mind’s eye. “The Thought Machine” is a cautionary tale, not overly well written, about what happens when we build machines to do all our thinking for us—the fun is the Frank R. Paul illustration of a gigantic thinking machine with gears, levers, vacuum tubes, a typewriter and other such stuff. The stomach story is likewise a throwaway, involving reciprocal stomach transplants. “The Eleventh Hour” is a scientific detective story involving a light-beam lie detector, which is notable mainly for its unconscious or casual racism involving a “Chinaman,” which was perfectly acceptable in 1927. The lettercol has the usual mixture of interesting letters, one of which asks that Gernsback stop printing “gruesome” stories (the author of this appears to be a Medical Examiner, too!); another which wants Garrett P. Serviss to write a sequel to “The Columbus of Space” in which the hero and heroine don’t get killed—to “make it right.” People are funny, all right.

And finally, we come to number 12, the March, 1927 issue. Volume 1’s last issue.

Amazing Stories Vol. 1 No. 12 (March 1927) Contents:

- “Idle Thoughts of a Busy Editor–Editorial by Hugo Gernsback

- “The Green Splotches”–(©1920) novella by T. S. Stribling

- “Under the Knife”–(©1896)–story by H. G. Wells

- “The Hammering Man”–(©1910) story by William B. MacHarg and Edwin Balmer

- “Advanced Chemistry–(©1923) story by Jack G. Huekels

- “The People of the Pit”–(©1918)–story by A. Merritt

- “The Land That Time Forgot”–serial (Part 2 of 3) by Edgar Rice Burroughs

- “Discussions” (Lettercol) with answers by the editor

Cover by Frank R. Paul, illustrating “The Green Splotches”

In his editorial, Gernsback talks about the higher cost of the new paper they’re using, but avows it’s worth it; readers seem to approve. He also decries the fact that for every reader who likes a story, an equal number of readers dislike it—but that’s an editor’s life for you; finally, he announces that they had 360 entries for their $500 short story contest, but they need more readers (hence, more money). Gee, where have I heard that before? The Stribling novella is an interesting one, combining a couple of genre tropes: a sort of “lost world” (in South America) with an alien “race”—and not too bad either scientifically or as an adventure story. The Wells story I can’t tell you anything about—those pages are blank in my copy! “The Hammering Man” is another scientific detective story, also involving a scientific lie detector; “Advanced Chemistry” is a throwaway story about a doctor (names are jocular; he’s Carbonic, his “negress” assistant is Mag Nesia) who attempts to revive the dead, with the usual fictional results. My reaction was, basically, “Meh.” The Abraham Merritt story is a classic—like all Merritt stories. If you haven’t made the acquaintance of Mr. Merritt, I urge you to find a copy of any one of ‘em, like Seven Footprints to Satan, f’rexample. This one involves (like some others he wrote) both a “lost race” and a “lost civilization” (and gold!). The Burroughs story is well known, but as Gernsback himself says, “To try to give you any idea of the second installment in a few lines would be a task equal to giving a resumé of the history of ancient Rome in several paragraphs. It can not be done.” But if you’ve seen one of the movies made from this, you know the story. Finally, the lettercol is the usual mixture. One surprising feature in Nos. 10-12 is the inclusion of an ad telling readers that the publishers want to purchase quantities of back volumes of Amazing. Why? Maybe to sell back to the readers? I dunno. And I absolutely love both the full-page ads in all these volumes (Study Chemistry! Become an auto mechanic! Make novelties at home!) and the smaller ads. They remind me of the ads in the comics I used to buy. Overall, I really liked visiting Amazing’s first full year. If you get the chance, do the same yourself; you’ll not only read some old fiction that still works, but you might have as much fun as I did!

I’d appreciate any comment on this week’s column you’d like to make. If you haven’t already registered—it’s free, and just takes a moment—go ahead and register, then you cancomment here, or you can comment on my Facebook page, or in the several Facebook groups where I publish a link to this column. Don’t feel you have to agree with me to post a comment; I might disagree with you, but I will take all comments into account. My opinion expressed here is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owners, editors, publishers or other bloggers. See you next week!

Steve has been an active fan since the 1970s, when he founded the Palouse Empire Science Fiction Association and the more-or-less late MosCon in Pullman, WA and Moscow, ID, though he started reading SF/F in the early-to-mid 1950s, when he was just a sprat. He moved to Canada in 1985 and quickly became involved with Canadian cons, including ConText (’89 and ’81) and VCON. He’s published a couple of books and a number of short stories, and has collaborated with his two-time Aurora-winning wife Lynne Taylor Fahnestalk on a number of art projects. As of this writing he’s the proofreader for R. Graeme Cameron’s Polar Borealis and Polar Starlight publications. He’s been writing for Amazing Stories off and on since the early 1980s. His column can be found on Amazing Stories most Fridays.

Recent Comments