OBIR: Occasional Biased and Ignorant Reviews reflecting this reader’s opinion.

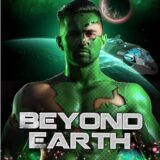

The Good Soldier – by Nir Yaniv

Publisher: Shadowpaw Press, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada, 2024

Cover art: by Nir Yaniv

Premise:

A “Confirmed Idiot, second class,” is drafted into the Imperial Navy of the United Planets. This does not bode well for the Empire.

Review:

Why this book? The author is American, and I normally review Canadian authors. However, my purview extends to promoting Canadian publishers, and Shadowpaw Press (founded 2018) is in independent Canadian press publishing authors such as Dave Duncan, Robert J. Sawyer, Edward Willett (the publisher), Leslie Gadallah, and others. (Shadowpaw is the name of Edward’s cat, by the way.) I very much want Canadian indies to survive and flourish, so I do not hesitate to promote them.

Besides, “The Good Soldier” follows a very fine tradition of military satire beginning with “The Good Soldier Švejk” (1921) by Jaroslav Hašek, “Turvey” (1949) by famed Canadian poet Earle Birney, “Bill the Galactic Hero” (1965) by Harry Harrison, and last but certainly entirely deserving of your attention, the five-volume autobiographical series by Spike Milligan, “Adolf Hitler, My Part in His Downfall” (1971), “Rommel? Gunner Who?” (1974), “Monty, His Part in My Victory” (1976), “Mussolini, His Part in My Downfall” (1978), and “Where Have All the Bullets Gone?” (1985).

Furthermore, I am of a generation whose parents experienced World War II and as a result military humour was part of everyone’s situational awareness and not just a narrow niche primarily of interest only to military families and anti-war protesters as it is now. When I was a kid the Canadian version of Reader’s Digest had a two-page section devoted to Canadian military humour as part of its mandate to provide family entertainment. American TV shows like Sergeant Bilko and McHale’s Navy were popular, as were military-comedy movies like “Mr. Roberts” (1955) and “Operation Petticoat” (1959). Safe to say military humour back then was equivalent to and part of normal everyday humour the average person was familiar with.

All that changed with the Vietnam war. The M.A.S.H. TV series, for example, while ostensibly about the Korean war was really all about sensibilities roiled by the Vietnam war. Up to that point the US military routinely supplied hardware and advisors to Hollywood productions, viewing it as good investment in light of recruitment and public relations possibilities. Not any more. The hardware in “Apocalypse Now” was for-hire services provided by the army and air force of the Philippines. Granted, lately there has been a spate of “traditional” war movies, like the sequel to “Top Gun,” but military humour by and large still tends to be anti-war humour rather than the “innocent” family war humour back in the day. So, what does a current military-satire novel reflect, past or present values?

A bit of both, actually. First of all, anyone who knows anything at all about military life takes the term “SNAFU” for granted. (I assume you are aware it translates as “situation normal, all fucked up.”) I’ll give you an example from real life. I recently read “Nautilus 90 North” (1959), an account of the first visit by an atomic submarine to the North Pole in August of 1958. There were two foiled attempts (ice conditions worse than predicted) followed by the successful mission which was nearly scuppered by a wee, slight problem. Seems, somewhere in one of the reactor condensers, there was an invisible hairline fracture leaking sea water onto “a critical piece of machinery not designed to resist the corrosive effects of salt water.” Underway under the ice this could cause the propulsion machinery to fail and doom the mission, the sub, and all the men on board. Endless hours of investigation failed to locate the leak.

The solution? The Captain sent the entire crew, in civilian clothes, into the wilds of Seattle searching gas stations for cans of a radiator additive known as “Stop Leak.” They brought back 140 quart-cans, at $1.80 a pop, to pour into the condenser system of a submarine which cost the US taxpayers 100 million dollars to build. They never did find the leak, but no matter, “Stop Leak” did the trick. The Nautilus never had that particular problem again.

This illustrates the nature of a SNAFU. An unexpected complication which regulations failed to predict and consequently, in a sense, was built into the system. Now, Pre-Private Fux, the “Good Soldier” in question, had been officially certified as a second class confirmed idiot on his home planet. He is rather proud of this. For one thing, it provides a firm base for his self-esteem. After all, nowhere to go but up. Though inherently and proudly lazy, he analyzed his problem and determined that his lack of focus and useless memory often get him into trouble. That being understood, he evolved a simple technique to avoid trouble which, as chance would have it, often precipitates the very trouble he is hoping to avoid.

First example, and his first misadventure, and the only one I will cite, happens when he boards the space frigate UPS Spitz along with a bunch of fellow draftees. They are all specifically warned not to touch the emergency handle in the airlock. Deeply concerned that his lack of attention would lead him to forget the instruction, Fux rests his arm on the emergency handle, gripping it firmly, so that not pulling it would remain uppermost in his mind whilst in the airlock. Alas, his fierce (momentary) attention to detail fails to achieve the desired effect. And yet, and yet, his superiors can hardly fault his logic as it represents a sincere effort to obey orders.

And that’s the most frustrating aspect of Fux from his superiors’ point of view. He always willfully and loyally obeys orders to the best of his ability. It’s just that ability is sadly lacking. And there are complications which the author builds on relentlessly. Fux tends to be literal-minded, so if orders issued are imprecise, if only because the officer assumes Fux fully understands the underlying background context, well, that’s just asking for trouble, isn’t it? Even worse, Fux is so danged cheerful and uncomplaining, mainly because everything leaves his head as soon as it enters. Cynical, jaded officers can be forgiven for suspecting a cleverly disguised ill-defined miasma of insubordination lurking just beneath the surface, but they find it impossible to pin down specific evidence that this is true. Fux is a true innocent.

Not that innocence is a shield of armour. The brass knows how to get rid of lesser beings who, regardless of guilt or innocence, wind up making their superiors look like fools to the lesser ranks. Trouble is, Fux is also lucky. Every fresh catastrophe he inadvertently brings about winds up making the Imperial Army & Navy, not to mention the officers who hate, loathe and despise him, look good in the eyes of the public, which in turn leads to him being promoted and being provided with fresh opportunities to screw things up to the advantage of the reputation of the Empire. This kind of hero they don’t need, and yet they do, because every other kind of hero is in short supply. Fux grows happier and happier while his superiors grow angrier and angrier. Makes for an interesting plot arc, at least in terms of emotions and motivations.

Now we come to the level of what I call “Strategic SNAFU.” Ordinary military humour encompasses the idea that the powers that be leading the war don’t really know what they are doing, that they are making it up as they go along. That generals and politicians are mere amateurs. The reality is often far worse.

Have you ever wondered why the British people didn’t protest the enormous casualty figures of the Great War? Daily figures like 30,000 dead, 40,000 dead, 50,00 dead? They were never told. British censorship and control of information during WWI was the tightest of any nation in the entire 20th century. Even now much information is classified and the figures you read in history books are often guestimates based on allied sources and even former enemy sources. (I suggest you read “Dying for the Truth: The Concise History of Frontline War Reporting” by Paul Moorcraft.)

The worst example of an idiot in charge I can think of (apart from Hitler) was revealed to me in the process of reading a four-volume history of the Eastern Front during WW I by renowned historian Pritt Buttar. The Commander of the Austro-Hungarian army, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, was an inflexible moron of the highest order. Put simply, Conrad believed only in the offensive, and placed bayonets over bullets, cavalry over artillery, frontal assaults over flanking attacks, and the shortest most direct routes over the most sensible, easily supported routes. For example, he ordered repeated attacks through rugged mountain passes in the middle of winter during blizzards against the Russians who were well dug in, equipped for conditions, and were superior in numbers of men, machine guns and artillery. His worst trait, like Hitler, was believing all the divisions he was shoving around on his maps were always at full strength, when often their numbers were as low as 10%. Roughly speaking, Conrad was responsible for about a million dead Austro-hungarian soldiers in just two years. Hence Hindenburg’s comment that fighting the Russians with Austro-Hungary as an ally was like going into battle tied to a corpse. Yet all the while the Austrian-Hungarian propaganda celebrated “victory” after “victory” and Conrad as a “hero.”

Well, the strategic SNAFU level in “The Good Soldier” isn’t quite that bad, but certainly is beyond even the worst imaginings of the grunts involved. The Empire, in addition to quelling outbursts of disloyalty from the ever-loyal colony planets, is in periodic combat on assorted alien worlds against infestations of hyper-intelligent and hyper-aggressive giant insects. Fortunately, as the propaganda machine assures everybody, every single encounter is a no-casualty affair resulting in total victory over the enemy. The surviving grunts of the United Planet Imperial army beg to differ, but they dare not. Truth is every battle to date has resulted in defeat and frantic retreat by the few survivors back to the motherships in orbit. Since official policy dictates eternal victory, the entire army and navy is delusional in its internal communications and relations. Everyone knows the truth, or some aspect of it pertaining to their own experience, but no one owns up to it. Euphemisms and lies are the basis of life aboard the warships, with reality hitting hard only when they are on-planet for brief periods of disaster.

As you might guess, thinking on the part of everyone, especially officers, is rigidly inside the box. Fux operates comfortably and naturally outside the box, if only because he does virtually no thinking at all. He’s capable of thought, but prefers not to because it complicates matters and why do that when it is so easy not to do anything at all and be perfectly content? Except this very flexibility of non-action causes endless problems for his superiors and they have no idea how to define them let alone combat them. Fux is the calm eye in the storm of his own innocent creation and can no more be defeated than the fates can be thwarted. No wonder his superiors are on the verge of going mad. Needless to say, this be the source of much hilarity on the part of the reader.

But there’s more to “The Good Soldier” than just Fux. Its satire has a number of targets. Military regulations, for one thing. Often they make sense when first formulated, but military technology and tactics tend to move on, leaving rigidly enforced regulations tangled around progress like unwrapped puttees. Many a grunt, NCO, and even some officers quickly learn to take advantage of obsolete regulations to serve their own interests. Yaniv has a lot of fun with this.

For another, there’s often fierce competition among officers, especially among administrative types. You thought brownnosing and betrayal were ubiquitous in civilian offices, it’s even worse in a military bureaucracy. Especially in the bloated ranks of unnecessary officers aboard Imperial Warships. Why perform well when all you have to do to get ahead is to frame your competitors for treasonable acts worthy of “re-education” or, even better, “recycling.” Mind you, competent officers who do useful things like keep the atomic engines running smoothly are relatively immune to such ploys, but fortunately they are rare and know enough to keep a low profile behind their competence. Fortunately, all the rest are potentially expendable.

But the touch of true genius in this book is the omnipresence of the computer monitoring conversation everywhere aboard the UPS Spitz. It’s guided by an AI eager to report the slightest transgression to, not only the Captain, but the nameless authorities on the home planet. The potential consequences are such that individual officers often startle themselves with the thought that something they just thought, including the current thought, they may have inadvertently muttered out loud and thus condemned themselves to death or worse. They’re a tight-lipped bunch, the officers onboard.

Here’s why I call this a touch of genius. Every single officer, unless they forget themselves in a moment of passionate outrage (so easy to do in the presence of Fux), in the full knowledge that “they” are listening, carefully weigh the implications of everything they say before they say it. Trouble is, it’s like a game of chess. Every move you make has multiple implications for the next moves to come, and not everyone is chess master enough to figure out what the ultimate consequences will be. The amount of panic-stricken brainstorming every officer indulges in is quite wonderful to behold. Often it leads to a moment of mental lock immersed in raw terror, occasionally instantly relieved by a gormless yet useful suggestion issuing from Fux’s calm and empty brain. This is why so many officers learn to embrace him as their saviour. It’s also why they hate him so.

I guess you could compare the level of panic and despair to the modern worry of many an old-fashioned, firmly within-the-box, tradition-minded individual that they can’t handle the kaleidoscopic onrush of modern “wokism” (however you wish to define it) such that they may well be left behind and possibly even be “punished” for failing to keep up. This is largely a monster-under-the-bed of their own creation. Simple truth is, every generation is different from the one preceding it, and the longer you live, the more obsolete you become in terms of relevant situational awareness. I’ve given up telling jokes about the Hindenburg, the Tzar, or the abdication of King Edward. No one seems to get them anymore.

In other words, this is not just a satire of military life and attitudes. It’s also a satire of the dangers of group-think and monolithic sainthood as manifest in many forms of modern propaganda. It’s far more relevant to your personal life and future than you may care to think. Frighteningly so.

CONCLUSION:

To sum up, serious though many of the underlying themes may be, overall “The Good Soldier” is easily accessible even to readers unfamiliar with military life and mindsets because it addresses universal human flaws and shenanigans in a hilariously satisfactory manner which leaves you smiling. Also, I can’t help but think Pre-Private Fux is meant to be a role model. We should be so lucky.

Find it at: < The Good Soldier >

Alas, I’ve never read any of the Flashman books, which explains why I didn’t mention them. I believe there was also a TV series? I vaguely recall seeing part of an episode and enjoying it.

At any rate, thank you for bringing up the Flashman books. If I’m ever in a mood for some light reading as an antidote to modern times, satire set in Napoleonic times sounds ideal.

Sounds good, Graeme. You forgot the “Flashman” books by George McDonald Fraser when citing military satires. Harry Flashman is Brown’s enemy/antithesis in “Tom Brown’s School Days,” but in Fraser’s books, he’s the incompetent antihero.

Everything he touches turns to gold despite himself; he is an arrant coward and braggart, but fate keeps making him the hero of battles and situations he barely survives. He’s sometimes the sole survivor, which makes it easier to become the hero according to his own account, but often his cowardly and self-serving actions are misinterpreted by everyone else as heroic.

This sounds somewhat similar, except that Yanov’s Fux is a lower-class doofus (according to your account; I haven’t yet read it), while Harry Flashman is an upper-class a*hole. You should try one or two; I think you’d enjoy them.