OBIR: Occasional Biased and Ignorant Reviews reflecting this reader’s opinion.

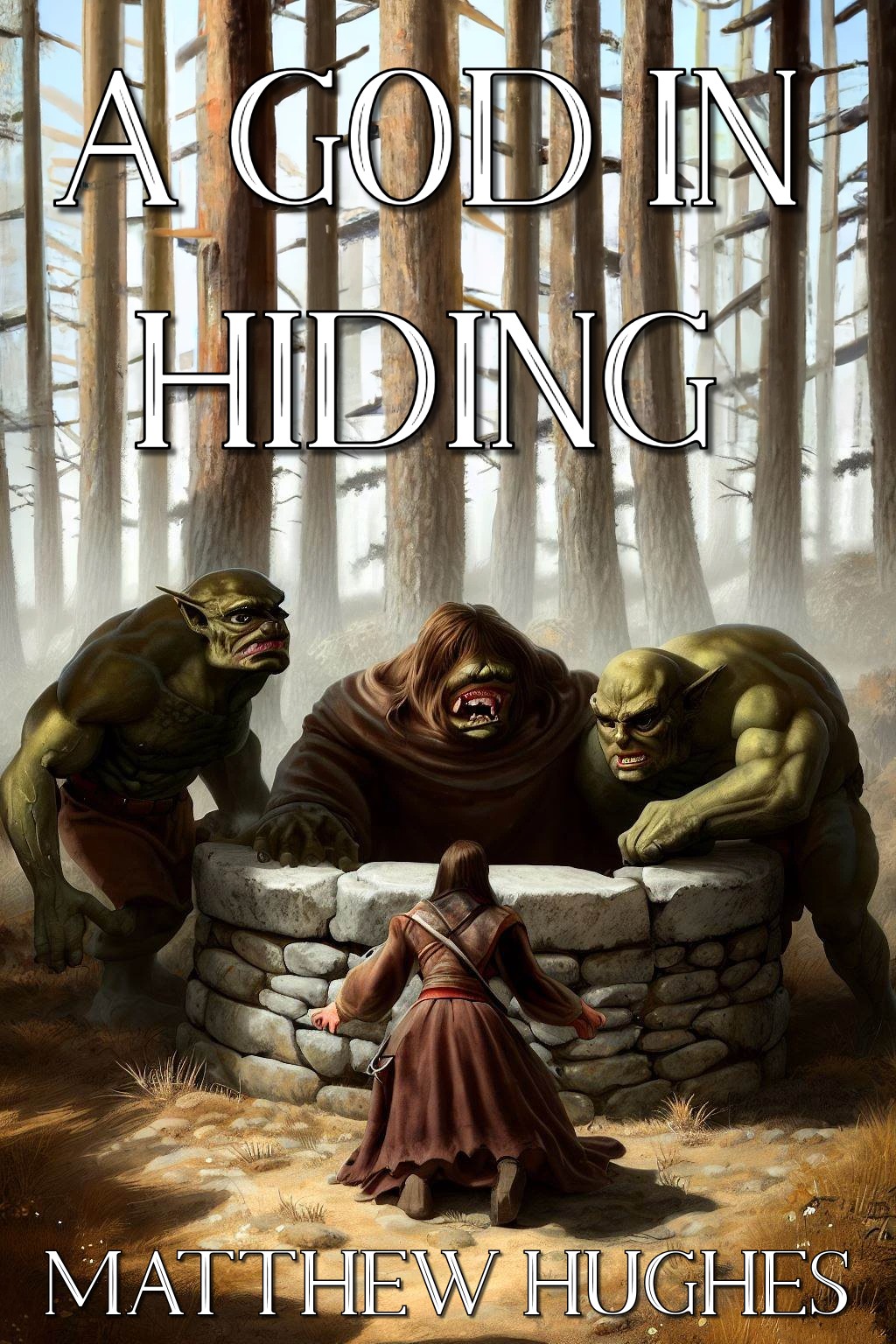

A God in Hiding – by Matthew Hughes

Published in 2023.

Premise:

A quest for a sacred object risks restoring a god to full power.

Review:

“A God in Hiding” is an extremely interesting book. It could be described as a quest fantasy (and that is my favourite form of fantasy) which involves much travelling and one confrontation after another with assorted less than friendly bad guys and monsters. This is the basis for many a book, or movie for that matter. One of the most ancient forms of story telling. It is a way of communing with our ancient ancestors who thrilled to the same sort of tales sung by bards and, before them, geriatric cave dwellers unable to hunt and hoping to earn a share of spoils. At least, that’s my theory. Point is this kind of tale goes way, way back in time.

This particular fantasy novel also incorporates the one question common to all civilizations throughout our recorded history. It’s the central theme of the quest. It is what makes this book so interesting. So delightfully interesting. But first, let me comment on some of the lesser elements of interest.

The key to understanding this book is the concept of exponential growth. It applies to everything: plot, character development, difficulty of task at hand, imminent threat and the implication of revelations.

For example, the protagonist Lieve Reder is “the captain of a riverboat owned by House Bernaglio in the oligarch-run city of Exley.” It took her a few years to work her way through the crew ranks into this job. She enjoys being her own boss when the ship is voyaging up and down the river connecting several city-states. After all, she doesn’t suffer fools gladly and since, in her opinion the majority of humans and sentient beings are absolute cretins, her position is as near to absolute freedom as she can conceive. Trouble is her ambitions nag her to do better.

Politics rears its ugly head and she is drawn into a shadow realm of dynastic squabbles, economic espionage, and the attentions of a secret police so brutal that altruism is grounds for dismissal. Being highly intelligent and vastly experienced dealing with average shenanigans it is all in a day’s work for Lieve. She turns the situation to her advantage.

Lieve’s boss, the widow Philaria, the ship’s owner and a prominent city aristocrat, is impressed. She sends Lieve on a quest to find an object technically owned by the widow but never actually delivered to her. To assist Lieve, a vat-grown humanoid named Dai is assigned to accompany her. That’s one “person” too many, in Lieve’s view, but she follows orders.

Threats and difficulties mount but Lieve and Dai work well together. They not only survive but come out of the affair with enhanced reputations. Unfortunately, resolving the quest is a lot like pulling a rotten tree stump out of the ground and exposing a nest of poisonous serpents. Turns out there is evil afoot bent on actively thwarting the goals of the widow.

Naturally, Lieve and Dai are sent on another quest, this one longer in duration and infinitely more dangerous. What ultimately is at stake is more than their reputation, more than their lives, in fact the “life” of existence itself. If they screw up it’s curtains for the universe and time to start over. The fate of the universe is a heck of a lot of responsibility to put on the shoulders of a riverboat captain but she feels up to it. Lieve always did like a challenge. Alleviates boredom.

Yes, growth. Start from the small and expand. Another example is the role of magic in this fantasy world. It does not suffer from the Gernsbackian flaw of being viewed with perpetual awe (Hugo felt that way about futuristic technology) because everyone takes magic for granted. It’s mostly used for petty, personal causes like love potions, keeping merchants honest, keeping hidden doors hidden, and the like. Generally useful for the person casting the spell, and no more than a nuisance for the individual confronting it. After all, counter spells are cheap.

A problem with the use of magic in fiction, however, is that it negates the natural laws science follows. So to speak, any problem can be solved by waving a magic wand. It’s the equivalent of the Rambo formula of being tougher and faster and more ruthless than everyone else on Earth so naturally victory is inevitable. T’aint so in the real world. Consequently, for a work of fiction to have any credibility at all, there have to be limitations placed on magic that render its use problematic.

Example, Lieve acquires a bauble that renders her invulnerable to harm by weapon, tooth or claw. The kind of thing useful to have when joining a caravan or entering a bar. It protects her from lesser forms of magic as well. But not from the most powerful forms of magic, and especially not from the power of magic wielded by the gods. And believe me, by the end of the book you get to see what divine power is capable of doing. It’s definitely a step beyond love potions. Again, the principle of exponential growth at work.

Now consider the matter of character relationships. The book begins with Lieve’s narrow focus on herself. She’s quite the loner, utterly self-reliant, and confident her instincts and intellect will see her through. Circumstances force her both to travel with Dai and trust him as a partner. A friendship forms, but not a “hey, I like you” sort of friendship. Instead, a friendship born of obeying orders, confronting threats and difficulties in common, a convergence of ambition and goals, and a joint desire to satisfy one’s curiosity. And always a friendship tinged by the potential of betrayal should necessity dictate. Come to think of it, more like an office friendship at work than a personal friendship. Different set of obligations all together. But just as enduring.

This is one of the aspects of the book contributing to its credibility, to its ambience of realism. Some characters pay lip service to morality, ethics and other fables, but all are constantly on guard against danger be it expected or unexpected. No matter what pretense is adopted for the sake of social intercourse, everybody takes for granted anybody can be a threat. This actually oils social interaction to run more or less smoothly because all are aware that survival is an ongoing game which depends on knowing the rules and knowing when to break the rules. The game is challenging and, for an enlightened few, kind of fun and the best game available. Evil wizards especially are prone to this view.

To illustrate this, consider that caravans are constantly in danger of being raided by nomads. Not a case of good guys and bad guys. Everyone takes for granted it is a perfectly natural relationship. In nature there is no good or evil, just instinctive necessity. Or as Albert Einstein is said to have replied when asked what he thought of the law of the jungle, “It’s a highly efficient energy transfer system.” No morality is involved. Predators must eat. Merely your personal misfortune if you happen to be the prey.

In this case, the nomads are constantly on the move. If they come across a caravan they loot it. Why waste the opportunity? Wise caravan masters hire nomads to guard the caravans. Nomads don’t mind fighting each other. It’s an opportunity to enhance personal prestige and, if they win, to acquire money and/or goods. A win/win situation, except for the losers. But they’re dead, so what do they care?

Furthermore, like many subsistence-level peoples, the nomads are insanely proud of their valour, contemptuous of potential prey, and prickly sensitive to perceived insult. Knowing this, intelligent people such as Lieve are able to run rings around them in negotiation, respectfully bending them to do what they want. Whereas a negotiator in love with the “noble savage” concept would probably wind up being staked to an ant hill. It pays to be cynical.

I think you are beginning to understand the high level of realism in social interaction manifest in this book. Not your bog-standard simple villagers and what-not. Everyone, including ogres and the dead, are out for the main chance. Doesn’t matter how isolated the community, all visitors must run a gauntlet of paranoia vs. self-interest on the part of the locals, whatever they are. Travellers must have their wits about them at all times. Fortunately, Lieve and Dai are well-equipped in that regard.

Matthew Hughes has had a long and varied career, among other things working for governments and even writing speeches for politicians. He knows a great deal about how the world actually functions. He puts a great deal of what he learned in his fictional worlds. The terrifying thing is, he probably tones things down a little. Safe to say, he understands how people exploit and take advantage of each other very well. This is why the characters he creates ring true.

Take the two evil wizards. Sometimes, being brothers holding lifelong grudges against each other, they oppose each other, and sometimes as necessity demands, they co-operate, but always purely out of self interest. Are they genuinely evil? They are to their victims. Not necessarily to their temporary allies. That law of nature again. Suffice to say their power and the level of the threat they offer grows tremendously as bit by bit they come closer to realizing their ambitions. The level of magic they utilise is just gosh darn unfair.

In the end, it all boils down to the gods. There are quite a few of them and all of them existing in multiple planes of existence such that most of their attention is distracted by affairs in realities other than what mere humans know. Even worse, the “society” of the gods is rigidly hierarchical, and there’s a tendency for responsibility to be kicked upstairs. Not to mention a distressing habit of justifying actions by saying “I was only following orders,” or so it is implied. Actually, more a case of the lesser gods following the laws of nature. It seems they were created by greater gods for specific purposes, given “instincts” they must obey.

So, again, from small to large. Lieve begins the book wondering if the current voyage up the river will earn a profit. She ends by trying to find out why the creator god created the universe in the first place. Exponential growth to her sense of curiosity I would say.

What begins as a simple quest adventure ends as a fascinating exercise in philosophy. Lieve masters any and all personal and societal conundrums, despite numerous obstacles and setbacks, meeting dire threats and intriguing characters along the way, only to wind up debating with the gods the very meaning of their existence, let alone hers. There are no easy answers. Especially since the gods depend on thought experiments and speculation as much as mere mortals. Seems the creator god forgot to explain the why when giving out instructions what to do.

Lieve desperately wants to go directly to the top to ask her question. She thinks the answer would solve every problem, every doubt, every conundrum. But would it? Nobody’s heard from the creator god in eons. Perhaps the purpose of life, the universe, and everything is unknowable. If true, what a bummer.

A cynical perspective on human nature and the way we operate is evident throughout the book. At the same time, there are wry flashes of humour which enliven the narrative. I particularly appreciate the “fact” that the gods, the lesser ones especially, are fallible and have limitations despite the enormity of their divine power. Furthermore, because of their inherent nature, they think differently from us humans. So much so, they are bemused by certain mental habits of ours which they find chuckle worthy and difficult to comprehend. This offers the refreshing viewpoint that being a mere mortal has its advantages. It seems it is much easier for humans to be happy and content. It’s hard to be a god.

Conclusion:

In addition to the fact the book has layers and layers of complexity revealed as the quest progresses, I would like to emphasise this is an eminently readable work precise and clear in both description and exposition, so much so that there is not a single stumbling block anywhere in the text. Nothing knocks the reader out of the story. Matthew Hughes is a master at drawing the reader into the tale and carrying them along like voyageur canoes in white rapids. No matter what twists and turns and unexpected bumps the plot speeds rapidly along and the desire to keep turning the pages is irresistible. Best of all, it’s great fun to read. A superior quest adventure fantasy. Highly recommended.

You can find it here: < A God in Hiding >

Recent Comments