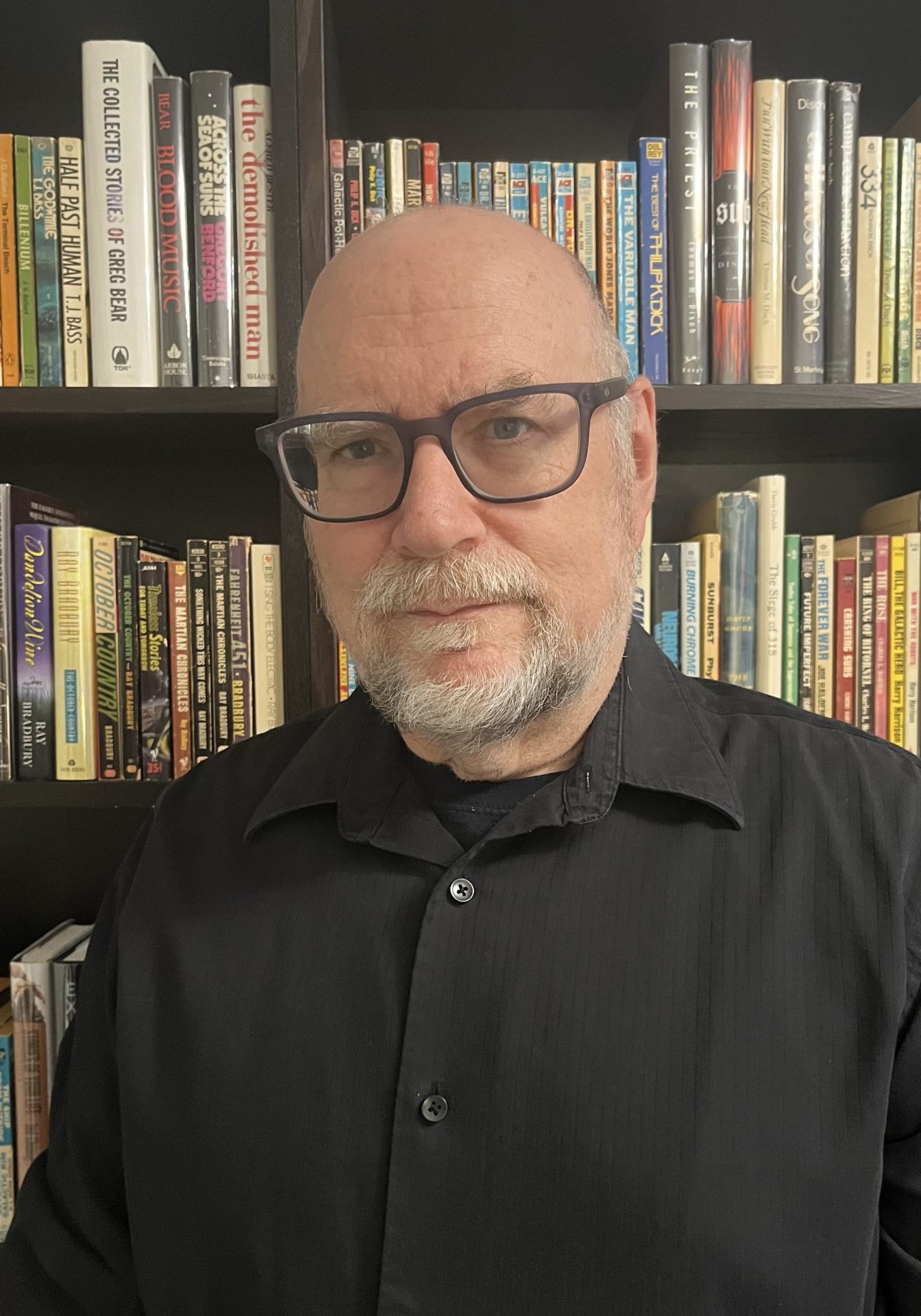

Robert Charles Wilson has been writing science fiction since the publication of his first novel, A Hidden Place, in 1986. His novels include Darwinia, Blind Lake, and Spin, which received numerous awards including the Hugo Award, the Grand Prix de l’Imaginaire (France), the Kurd Lasswitz Prize (Germany), and the Seiun Award (Japan). His short fiction has been collected in The Perseids and Other Stories. His work-in-progress is a novel called Forty Million Summers. He lives near Toronto with his wife, Sharry.

Robert Charles Wilson has been writing science fiction since the publication of his first novel, A Hidden Place, in 1986. His novels include Darwinia, Blind Lake, and Spin, which received numerous awards including the Hugo Award, the Grand Prix de l’Imaginaire (France), the Kurd Lasswitz Prize (Germany), and the Seiun Award (Japan). His short fiction has been collected in The Perseids and Other Stories. His work-in-progress is a novel called Forty Million Summers. He lives near Toronto with his wife, Sharry.

Excerpt: From Owning the Unknown (A Science Fiction Writer Explores Atheism, Agnosticism, and the Idea of God) by Robert Charles Wilson

I was a week away from my thirteenth birthday when I first attended a church function voluntarily and without the company of my parents. It was a Wednesday night in December, the weather in the Toronto suburb where we lived was cold and getting colder, and I walked the three blocks from our house to the local Baptist church at a brisk pace, pausing only once or twice to kick at the crusts of ice that had begun to congeal on curbside puddles.

I wasn’t ordinarily enthusiastic about church or anything connected with it. I managed to sit through Sunday services without complaining—usually—but I had resisted Sunday school so often and so vocally that my parents finally let me skip it altogether. But this occasion was different. What had lured me out into the chilly night was the promise of a display of ultraviolet fluorescence.

Two Sundays ago I had spotted an announcement in the mimeographed bulletin tucked into the pews next to the Bibles and the hymn books. The subject was something about gospel stories for children and teens, but it was the line promising “a glow-in-the-dark black light presentation” that caused my own eyes to light up. I was a precocious reader, already fascinated by anything related to science, and lately I had been reading about the physics of light, possibly in one of Isaac Asimov’s science guides for general readers. And although there was much I didn’t understand, I had successfully grasped the concept of ultraviolet light—that is, light of a frequency beyond the visible spectrum, a kind of light human eyes can’t see. And I knew UV light would cause certain dyes to fluoresce in glowing, gaudy colors. This was the mid-1960s, a few years before black-light Jimi Hendrix posters became a fixture in the bedrooms of suburban teenagers, and I was determined to see the phenomenon for myself, even if it came at the price of a sermon.

I bounded up the church stairs, left my winter jacket on a peg in the cloak room, and followed a trail of handmade signs to a meeting room off the main chapel where folding chairs had been set up in front of an easel. A pair of amiable adults—maybe the resident Sunday school teachers; I didn’t recognize them—glanced at the wall clock and eventually introduced themselves to the gathered multitude, about a dozen adolescents including myself. Most of the attendees were around my own age, and only a few seemed enthusiastic about what was to come. But we dutifully took our seats when we were asked to.

The doors were closed. The presentation began. Disappointment immediately set in. Propped on the easel was a flannel board. Flannel boards, also called flannelgraphs, were visual aids then (and apparently still) popular with evangelical Sunday schools. The board was covered with a swatch of fuzzy cloth to which fabric cutouts of Bible characters could be affixed for the purpose of illustrating a story. Tonight’s story, unsurprisingly, was the Nativity. For several interminable minutes the two youth evangelists escorted a slightly threadbare Joseph and Mary from one palm-tree-and-donkey mise-en-scène to the next. No black light. I was on the verge of raising an objection—false advertising!—until we reached the manger, the star, the wise men from the east. That was when a girl at the back of the room was delegated to turn off the overhead lights.

One of the teachers switched on a UV source mounted over the easel, and the Star of Bethlehem promptly lit up like a plum-colored supernova. So did the manger, the holy family, the magi, their gifts; so did various loose threads, dust specks, and stitched hems on our shirts and shoes. The woman at the flannelgraph wore a hairband that radiated a blue glow like an icy halo.

I knew how this worked. Energetic but invisible UV photons struck chemical compounds in the dyed fabric like incoming ordnance, causing the atoms to kick out new photons at a lower, visible, energy level. The result was this wonderfully ghostly coral-reef radiance. The Nativity story itself was infinitely less interesting, familiar not just from church but from school pageants and the Christmas specials that aired on television every year around this time. I was already a science fiction reader, though not a particularly sophisticated one, and I understood the Nativity in science-fictional terms: a cosmic being makes contact with Earth by sending an emissary disguised as a human child. It was a neat enough idea. It reminded me of a John Wyndham paperback I had recently read, Village of the Damned, in which aliens plant their hybrid offspring in the wombs of unsuspecting women in a small English town—though this version would have to be called Village of the Blessed. The premise was good, I thought, although the Gospel narrative that followed from it was more than a little confusing. But I wasn’t here for the storytelling. I was here to see the world made incandescent by invisible radiation.

And so it was, though it ended all too soon. The overhead lights were switched on. The flannelgraph morphed back into a low-rent Sunday-school prop. The woman with the radiant hairband took a seat, and the man who had helped her narrate the story smiled and asked whether we had any questions.

I raised my hand. He nodded at me.

I stood up. “Bees,” I said, collecting my thoughts.

“Bees?”

“Did you know they can see ultraviolet light? Bees, I mean. They have eyes that can see ultraviolet light. It helps them find flowers.”

Someone giggled. The teacher thanked me for that interesting information and looked pointedly for another raised hand. I sat back down, blushing. All this was followed soon enough by an invitation to commit our lives to Christ.

Altar calls inevitably made me uncomfortable, whether in church or at the climax of the Billy Graham rallies my parents watched on TV. I didn’t understand them. The smiling adult standing at the flannel board seemed well-intentioned, but it was as if he wanted me to sign a contract I hadn’t read or buy a product I wasn’t sure I wanted. So I slumped in my chair, hoping not to be noticed, and when that tactic failed I pled the necessity of a bathroom call, rescued my jacket from the cloak room, and escaped into the December night.

Snow had started to fall. Fat, perfect snowflakes danced to gusts of wind, made gauzy circles around streetlights, blurred the lenses of my glasses. The bees had all gone wherever bees go in winter, but I wondered what a bee might see on a night like this. What I had said was true: bees and many other insects are sensitive to ultraviolet light, and flowers that have evolved to attract pollinating insects often display patterns invisible to human eyes. (I imagined petals lit up in luminous grids, like cities seen at night from an airplane.) Did crystals of snow, too, scatter light in colors beyond purple? Was this blanket of monochromatic whiteness, for some other creature, a glittering rainbow?

I was happy enough with the evening, though it taught me I shouldn’t entirely trust announcements in church bulletins. Whatever the intentions of the smiling and soft-spoken youth evangelists who conducted the session, I had been granted at least a quick glimpse of the world beyond its visible limits, a token of a realm not ordinarily available to human senses. (It didn’t occur to me then that the evangelists might have described their faith the same way.)

But the event left other questions in my mind, more troubling ones. Why did so many people want me to hold a certain opinion about God, and to declare that opinion publicly? Why did Bible stories, presented as fact, feature so many of the hallmarks of fantasy—miracles, apparitions both demonic and angelic, covenants negotiated with cosmic powers? What exactly was I being asked to believe, and why did it matter? I didn’t mind singing along with the hymns on Sunday—or at least mouthing the words and pretending—but if someone were to ask the question directly, how would I answer it? Did I believe in God? Or was I that unmentionable thing, an atheist?

Amazon US https://www.amazon.com/

Amazon Canada https://www.amazon.ca/Owning-

Kermit is an omnicompetent individual who grew up in a former bawdy house before relocating to his state’s capital city. His family includes many talented artists and an uncle who founded The Church of Bigfoot. He has a passion for storytelling often exploring new ways to engage audiences.