We are, naturally, referencing the original 1951 version of this film, not the Keanu Reeves remake which should be converted to celluloid and THEN condemned to hell, and nothing more need be said about that unfortunate abomination ever again.

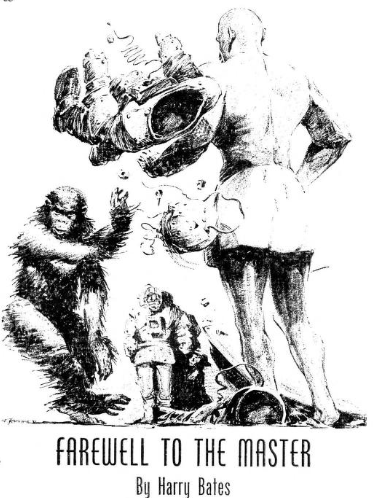

Anyone who gives any consideration to the history of the science fiction genre (if you are new around here, respect for history is de rigueur as it remains our only reliable indicator of our future) at least mentions this film, if not placing it high up on a listing of top films, and they do so for several reasons: it’s one of the first feature films to treat the genre with respect. It is well-acted, the SFX are minimal so there are few opportunities to point out the strings and it is based on a short story that was published in an honest-to-goodness Science Fiction pulp magazine – Astounding Science Fiction as it was titled at that point (October, 1940) – a story that would have been entirely overlooked had it not been for the adaptation. The issue of Astounding it originally appeared in also carried the second installment of Slan by AE van Vogt, and no other story could compete with van Vogt’s short novel at the time because it strongly suggested that science fiction fans were society’s supermen…forget the Nazis, Fans are (or were) the true

Anyone who gives any consideration to the history of the science fiction genre (if you are new around here, respect for history is de rigueur as it remains our only reliable indicator of our future) at least mentions this film, if not placing it high up on a listing of top films, and they do so for several reasons: it’s one of the first feature films to treat the genre with respect. It is well-acted, the SFX are minimal so there are few opportunities to point out the strings and it is based on a short story that was published in an honest-to-goodness Science Fiction pulp magazine – Astounding Science Fiction as it was titled at that point (October, 1940) – a story that would have been entirely overlooked had it not been for the adaptation. The issue of Astounding it originally appeared in also carried the second installment of Slan by AE van Vogt, and no other story could compete with van Vogt’s short novel at the time because it strongly suggested that science fiction fans were society’s supermen…forget the Nazis, Fans are (or were) the true  ubermenschen…and not because of religion or politics, but because they possessed superior intellect and “abilities far beyond those of mortal men”. (I mean, every Trufan already knows this, its just that we no longer shout it in the streets…or even in convention hallways.)

ubermenschen…and not because of religion or politics, but because they possessed superior intellect and “abilities far beyond those of mortal men”. (I mean, every Trufan already knows this, its just that we no longer shout it in the streets…or even in convention hallways.)

A fun digression, but digression nonetheless.

The Day the Earth Stood Still is often critiqued as a Christian allegory, with Klaatu taking the role of Jesus, come to Earth to warn us of our folly, paying the ultimate price, being resurrected and leaving us all behind to wonder and glance up at the sky in fear and trepidation.

The fact that script writer Edmund H. North has essentially indicated that references to the Christ tale were intentional is actually something of a red herring, because those who read those statements and come to the seemingly logical conclusion (the film is a Christ allegory) forget the fact that Directors (in this case Robert Wise) do not have to film scenes in the way that script writers write them.

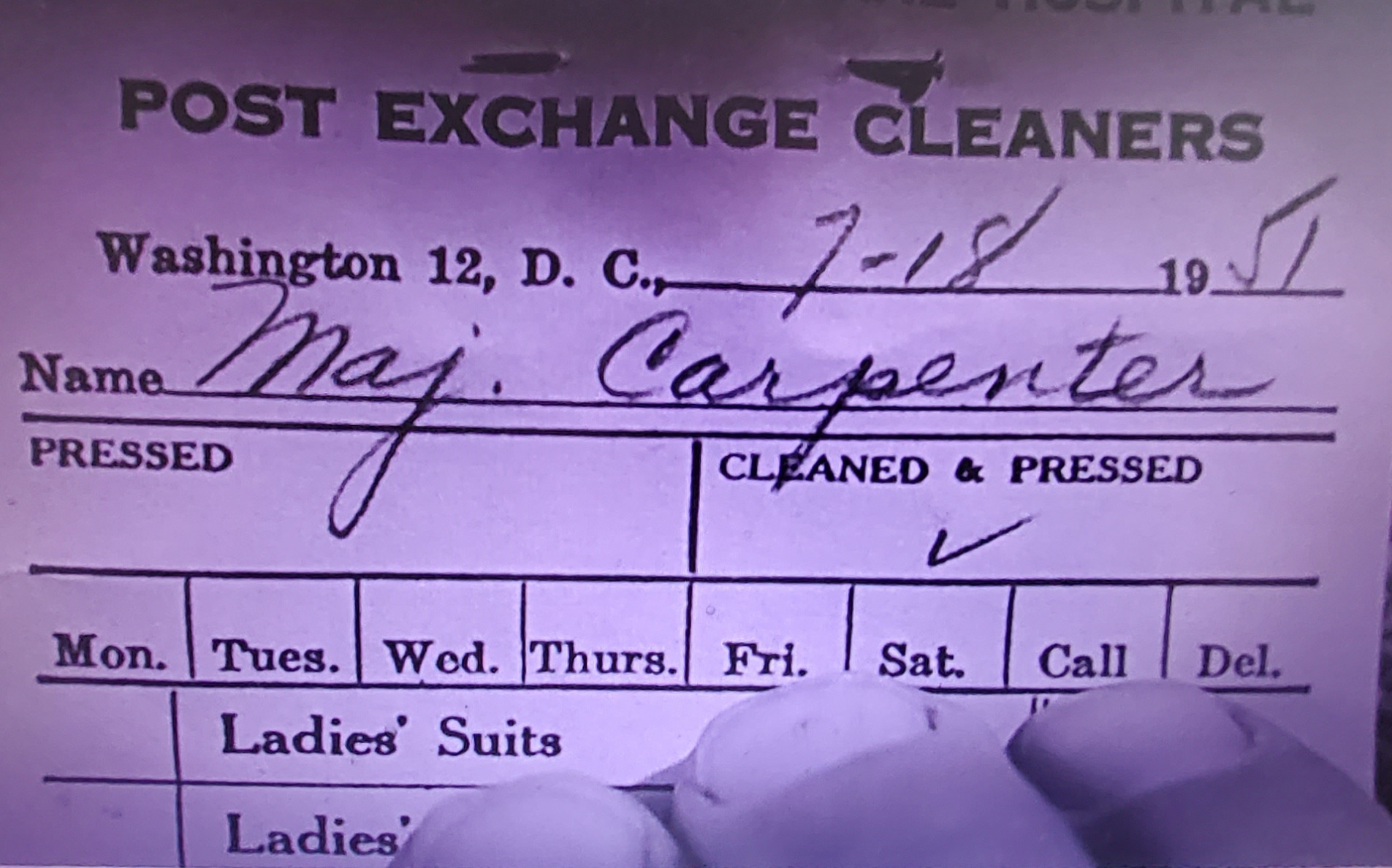

This fact becomes pretty obvious during the scene when Klaatu has escaped Walter Reed hospital and is looking for some place to stay. In preparing to enter the home where he will eventually take a room, Klaatu happens upon a dry cleaner’s tag pinned to the sleeve of the jacket he took from the hospital.  It states “Maj. Carpenter”. Klaatu smiles ruefully, almost as if acknowledging someone else’s joke, crumples up the tag and throws it away. We then see the initials on the briefcase he is carrying “L.M.C.”. Obviously, Major Carpenter’s initials are “L.M.”.

It states “Maj. Carpenter”. Klaatu smiles ruefully, almost as if acknowledging someone else’s joke, crumples up the tag and throws it away. We then see the initials on the briefcase he is carrying “L.M.C.”. Obviously, Major Carpenter’s initials are “L.M.”.

Shortly there after, Klaatu gives the residents of the boarding house his name as “Carpenter” – or, as others would have us believe, “J.C.”, obviously meant to invoke “Jesus Christ”.

But given so many other scenes in the film (which I’ll go into momentarily), I have to say that this and those other scenes are not the film engaging in Christian allegory, they are the director’s REJECTION of the script writer’s shoe-horning in of the Christ allegory.

Klaatu is breaking the fourth wall when he throws away that laundry ticket. His expression is one that clearly registers the original intent, and then just as clearly, rejects it by throwing it away.

This, I believe, was Robert Wise’s subtle message to movie goers that all was not as it seemed, neither on the surface or directly below the surface.

The film is actually a very strong statement against illogical, emotionally based reasoning and promotes the use of the logic and reason of science.

This point is made both with dialogue, often very pointed dialogue, through imagery (the aforementioned) and through the use of logic by audience members to fill in blanks – and to leave those audience members who don’t get it in continued ignorance.

I’ll not make you wade through the entire film to learn one example of the latter.

At the denoument of the film, Klaatu has been “resurrected” by his advanced technology. He delivers his final speech. That speech and an earlier explanation contained the information that Klaatu’s people do not use violence and do not allow its citizens to come to harm through the use of violence.

Without saying anything else, without issuing any instructions, Klaatu returns inside his ship and begins to take off – the ship issues a hum and begins to glow.

All of the stupid monkeys in the audience – including Professor Barnhard – evince some concern and begin easing away from the ship, then shortly thereafter we see everyone in the crowd fleeing in panic.

A panic that was completely unnecessary – Klaatu’s people do not allow others to come to harm through violence. If it had been unsafe to remain in close proximity to the ship while taking off, Klaatu would have informed everyone that they needed to move to a safe distance…but by his lights, everyone on Earth has ALREADY received that instruction, though not explicitly so. But it would be obvious to anyone utilizing logic rather than emotion in their reasoning.

That’s just one example to set the point here. We’ll go through the film sequentially to more strongly substantiate it.

But before that, we’ll return to the Christ story allegory.

In addition to the Christ story, a lot of folks have remarked over the years that the film is also a warning about atomic energy…or a fairly subtle version of the “red menace”. McCarthy’s House Unamerican Committee was front and center during the film’s production and release and the Hollywood Blacklisting of cast and crew was in full swing. Indeed, Sam Jaffe, who played Professor Barnhard, was blacklisted for some time. Wise hired him for the role of Barnhard despite the blacklist.

Why? Probably because Jaffe had been blacklisted based on illogicality and ignorance (fear and ignorance were McCarthy’s stock in trade).

The Cold War was raging, but that, too, is a secondary theme or, rather, just one of the elements comprising and supporting the films real theme, which is actually summed up at the end of the first act of the film.

Klaatu is speaking with Mr. Harley, the state department representative, while Klaatu is being held under guard. Klaatu, very baldly and forcefully states, when Harley describes the difficulties of trying to get all of the world’s heads of state to agree on anything that:

Harley: Your impatience is quite understandable.

Klaatu:

I’m impatient with stupidity. My people have learned to live without it.

Harley: I’m afraid my people haven’t. I’m very sorry… I wish it were otherwise

And the rest of the film goes on to prove, at least for the human beings depicted, that Harley’s assessment is spot on.

Every single time that humans in the film (with two exceptions – Bobby and Helen) have an opportunity to use logic based on the information available to them at the time, they fail to do so, pointedly allowing emotion to overcome reason.

Side note: Don’t know if you’ve noticed, but clocks stop appearing in the film after Klaatu has landed. Subtle. No need for clocks because time has run out.

Lets take a look at Klaatu’s concluding speech that pretty much ends the film.

Klaatu has been resurrected by his science and technology, the very same science and technology we are told is a more advanced version of our own. In other words, we, the human species, are capable of accomplishing the same things that Klaatu demonstrates. Immediately following the resurrection sequence there is this scene

Benson: I thought…you were…. (dead)

Klaatu: I was

Benson: (Turns and looks pointedly at Gort) You mean he has the power of life and death?

Klaatu: No. That power is reserved to the Almighty Spirit. This technique, in some cases, can restore life for a limited period.

Benson: How long?

Klaatu: You mean, how long will I live? That, no one can tell.

Note also that we are shown an entire sequence of Klaatu’s resurrection. The only things in evidence are technological in nature. There’s no hocus pocus, no prayer, no wailing invocations, no emotional pleadings, merely a robot performing what are essentially routine tasks. This scene is lingered on for some 3 plus minutes (seconds are precious in feature films) and concludes with the following dialogue between Klaatu and Helen:

This is a bit problematic because the “almighty spirit” is invoked and we’re told that the power over life and death is reserved for that entity and yet, we watch a dead man brought back to life through technological means.

This is a bit problematic because the “almighty spirit” is invoked and we’re told that the power over life and death is reserved for that entity and yet, we watch a dead man brought back to life through technological means.

But it really isn’t problematic when looked at in the proper light. Imagine someone whose heart has stopped and is then re-started with a defibrillator. Someone involved is very likely to say something like “Thank God” when the application of the technology (which “God” had nothing to do with) proves successful. Invoking a deity in such circumstances is not uncommon, even when no one believes in such things.

Using the phrase “power over life and death” is clearly a spiritual reference, and that reference is rejected by Klaatu. It refers to more than the presence or absence of a heartbeat and is meant to remind us that there IS another way of interpreting this story, but that it is not the way we’re supposed to interpret that story.

It’s another scene almost exactly like the throwing away of the dry cleaning stub: yes, the film has raised the issue. No, that’s not what we’re trying to address.

Once you realize that the theme of the film is not Cold War fears or Christian allegory, but is, instead, an indictment of ignorance, all manner of clues and hints become revealed. It’s actually very, very cool and subtle, because it requires the strict application of logic as applied to the facts presented by the film, it demands that audience members employ a scientific rationale in order to be able to see the film’s actual message.

For example: when the crowd watches as the door to the saucer opens for the first time, there are numerous crowd reaction shots: all of the adults evince concern, possible panic and the beginnings of fear, while children’s reactions, filmed in contrast to the adults’, is one of wonder and anticipation. (That old sense of wonder.) Either the children are ignorant of reality, OR, they are ignorant of the indoctrination that leads to adults abandoning rationality in favor of emotion. Nothing we have seen in the film up to that moment demonstrates anything to be fearful of. (Caution, sure…fear, no.) And if the adults in the crowd were being reasonably cautious (from having logically assessed the situation), they’d not all be crowded so closely around an unknown object that was capable of they knew not what.

But there they are, allowing the conflict of curiosity and fear to trap them in a ridiculously exposed and vulnerable position if something bad were to happen.

Helen Benson’s boyfriend, insurance salesman (and isn’t insurance a business based in irrationality yet couched in math and logic?) Tom Stevens seems a reasonable individual until greed and ambition rear their ugly heads, at which point he becomes more than willing to abandon Helen rather than give up on “Being a Big Man” when he helps the FBI capture the “spaceman”.

Subtler digs abound throughout the movie: Mrs. Crockett (the boarding house owner) remarks that Klaatu (now portraying John Carpenter at the boarding house) is

Crockett: a long way from home

Carpenter/Klaatu: How do you know?

Crockett: I can tell a New England accent from a mile away.

Yes, it is meant to be humorous, but Klaatu’s expression right before the cut reveals that he considers such unfounded speculation to be ridiculous.

Right before that scene, Carpenter enters the rooming house and stands in the shadows. His presence startles everyone and Crockett – the owner of a boarding house, reacts fearfully, asking “What do you want?”

Mayberry RFD’s own Aunt Bee (Frances Bavier, who plays Mrs. Barley), during breakfast at the boarding house, declaratively states that the saucer must be from “you know where” – based on no evidence whatsoever. Yes, it is a nod to the red scare but – the ship is not from the Soviet Union and that country is not a threat in this context.

However, the scene that puts the capstone on this particular interpretation is one that takes place when Klaatu and Professor Barnhard (smartest man in the world) finally meet.

Klaatu (as Carpenter) is rounded up by the FBI and the military and delivered to Barnhard’s office. Previously, Klaatu had written out the solution to a physics problem on Barnhard’s blackboard. Barnhard asks how Carpenter knows that the solution works:

Barnhard: Have you tested this theory?

Klaatu: I find it works well enough to get me from one planet to another

(Barnhard reacts with surprise and dawning recognition.)

Klaatu: I am Klaatu

Barnhard then goes to his office door and dismisses the military guard, stating that “I know this man”

Klaatu: You have faith, Professor Barnhard

Barnhard: It isn’t faith that makes good science, Mr. Klaatu, it is curiosity

Now think about this. Given the scene, what Klaatu is actually talking about is “trust”, not “faith”. Religiosity is entirely absent from this scene until Klaatu uses the word “faith”.

There are two reasons for this. This first is to give Barnhard the set up for clearly stating that this film is not about faith – it isn’t a religious allegory but is, instead, devoted to logic, reason and science.

The second reason is to allow both Barnhard and Klaatu to inform the audience that their own actions are also based on rationality, logic and scientific principals. Klaatu is testing Barnhard with that remark. If Barnhard is indeed the smartest mind on the planet, it is reasonable for Klaatu to assume that he has rejected religion in favor of science as a basis for logic. Someone on the borderline, someone who gives equal weight to either magisteria (religion, science) would not immediately reject the influence of faith on his decision to trust Klaatu, but would answer in the way that Barnhard did, by rejecting its influence….

The Day The Earth Stood Still is not Christian allegory, nor is it a red scare film or commentary on the antics of Senator McCarthy, although those making such claims can be forgiven as both of those elements are present in the film. It is a declarative statement that logic, rationality and science are the way forward for the human species, and that in order to get there, they must rid themselves of their penchant for reacting irrationally in the face of the unknown.

Klaatu’s final speech pretty much puts that into summation:

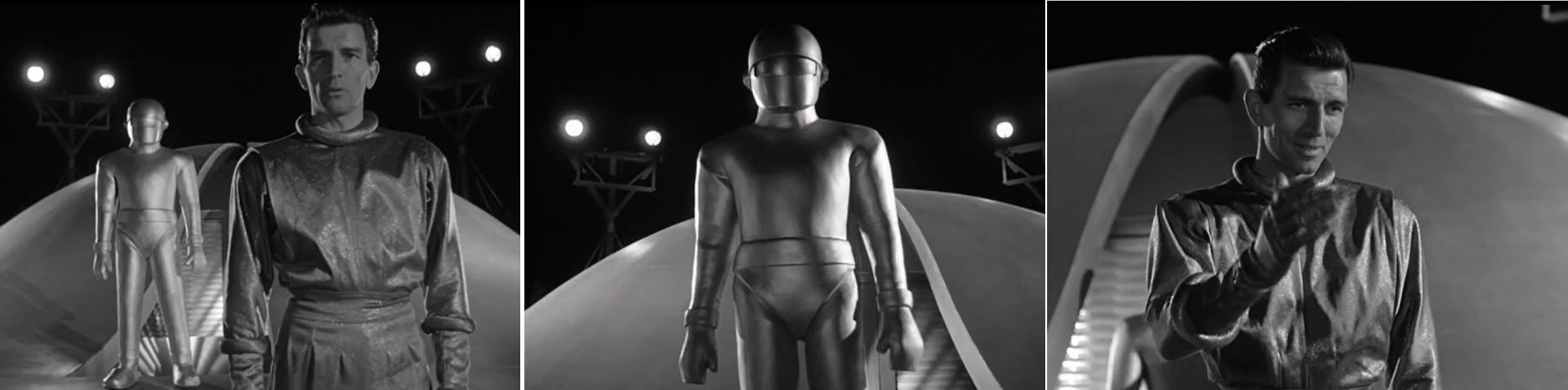

It bears taking a close look at the actual scene and the visual elements that surround Klaatu’s final speech.

The world’s leading scientists have been gathered at the saucer to listen to Klaatu’s announcement (the one he traveled to Earth to make). Prior to that, the military hunted down and killed Klaatu (as Carpenter). Helen goes to the park and activates Gort, who captures Helen, places her inside the ship and then retrieves Klaatu’s body, taking it to the ship to resurrect him.

Barnhard is told by the military that they must leave the park because the robot is on the loose and safety can not be assured. Barnhard takes the podium and is announcing the need to leave when the door on the spaceship opens and Gort steps out. (Even the scientists attending the speech react in fear.)

We watch as Gort takes up station, Klaatu emerges with Helen, who quickly exits the scene. (Helen, who was “captured” is released unharmed, with no coercion needed) and all of the faces in the crowd – scientists, soldiers and citizens, turn to Klaatu:

Klaatu: I am leaving soon, and you will forgive me if I speak bluntly. The universe grows smaller every day, and the threat of aggression by any group, anywhere, can no longer be tolerated.

There must be security for all, or no one is secure.

Now this does not mean giving up any freedom, except the freedom to act irresponsibly.

Your ancestors knew this when they made laws to govern themselves and hired policemen to enforce them.

We of the other planets have long accepted this principal. We have an organization for the mutual protection of all planets and for the complete elimination of aggression.

The “test” of any such higher authority is, of course, the police force that supports it.

For our policemen, we created a race of robots. Their function is to patrol the planets in spaceships like this one and preserve the peace.

In matters of aggression, we have given them absolute power over us.

This power can not be revoked.

At the first sign of violence they act automatically against the aggressor. The penalty for provoking their action is too terrible to risk.

The result is, we live in peace. Without arms or armies, secure in the knowledge that we are free from aggression and war. Free to pursue more profitable enterprises.

Now we do not pretend to have achieved perfection, but we do have a system, and it works.

I came here to give you these facts.

It is no concern of ours how you run your own planet. But if you threaten to extend your violence, this Earth of yours will be reduced to a burned out cinder.

Your choice is simple: Join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration.

We shall be waiting for your answer. The decision rests with you.

Gort. Baringa.

Klaatu then salutes (or give an alien goodbye wave) Helen in the audience, the capstone of this final statement. Helen is, along with her son and Barnhard, just about the only humans on the entire planet who “get” the message; they are the ones who “trusted but verified” Klaatu. They are the ones who did not act irrationally out of fear. It is their example that the human race must follow if the Earth is not to become a burned out cinder.

There are a number of other telling moments and interesting scenes that support this thesis at least tangentially by demonstrating that surface detail is not the whole story with this movie. They’re easy to miss though, as, for example, the hosts of TCM’s airing of this film, who missed the fact that Gort the “menacing robot” does not appear until AFTER humans have demonstrated aggression against Klaatu. Early in the film, this manner of presentation underwrites Klaatu’s statement (above) from the ending. At every turn, Klaatu’s statements are revealed to be both reliable and truthful.

Another scene: a radio reporter is interviewing members of the crowd gathered to see the spaceship. He abruptly cuts off his interview with Klaatu who is being logical because it is not a sensational enough answer. (Also during that scene the radio reporter fairly pointedly ignores a woman of color in the crowd…an even subtler demonstration of ignorance and fear.

It’s also perhaps telling (these days more so than in 1951) that Klaatu does not seek out the media to assist him in spreading his message world wide. The radio reporter’s pursuit of sensationalism is probably a not-so-subtle dig at the way the media amplified McCarthy’s fear mongering.

A few questions do come up during this close examination though. The major one is – how come the Earth isn’t rendered into a burnt out cinder when the tank commander shoots Klaatu? (Probably only restrained by Klaatu…which does go against Klaatu’s statement, later, that their police robots act automatically and their actions can not be revoked.)

Another is the fact that Klaatu and Helen are driven around by a remarkably incurious cab driver, one who can clearly hear what they are saying in the back seat, which are the instructions on how to control Gort. It would have been a different movie, but that cabbie could have sold that intel for a pretty penny.

And another is the, to contemporary eyes at least, complete lack of concern by both Tom and Helen in leaving Bobby alone all day with a complete stranger (one who expresses a special interest in spending time with Bobby, although of course not for pervy reasons). Things were a lot more lax back then (at the age of five I had the run of my neighborhood, unsupervised), but that scene strains credulity. It’s somewhat redeemed later on when it is revealed what a jerk Tom Stevens is, but it still jars (and does bring Helen’s own powers of reasoning into question a bit. We all have lapses in judgement though and the important thing to measure is what we do after our lapses. Helen does just finer).

Neon lights are observably blinking during the half hour that Klaatu stops all electrical power on the Earth (except for special circumstances, but I don’t think a movie marquee fits the special circumstances bill) – probably unavoidable given the technological limits of the era.

And, last but not least, the very thing teased in the title: Have you noticed at this point that the famous “Roddenberry future” is actually articulated in the closing speech by Klaatu, some 14 years before Star Trek became a thing? If not, go reread that speech above and then come back here and tell me that Roddenberry wasn’t at least influenced, if not inspired, by those lines.

Roddenberry had been a policeman. His first television scripts were police procedurals. He was also a reader of science fiction and, in the 1950s, he probably read Astounding Science Fiction magazine. No telling if he was ever exposed to Bates’ Farewell to the Master but he very likely saw this movie in 1951 and would have been sensitive to things involving police. A race of interstellar robotic police tasked with making sure everyone plays nice so that they can pursue more important things like learning about each other?

Yes, Klaatu’s “organization of mutual protection for all planets” (UFP?) has a different take on the non-interference directive of Star Trek, but then again, you can’t make much of a show out of flying saucers appearing at various planets and then burning them out because a couple of school kids had a playground fight, but the gist is there. The idea of attempting to arrange things in a way that emphasizes peace, understanding, mutual protection and pursuing knowledge are all in there, and it wouldn’t surprise me at all of if The Day the Earth Stood Still isn’t responsible for the general philosophical underpinnings of Star Trek, just like another famous 1950s science fiction film – Forbidden Planet – provided much of the inspiration for the look and feel of the technologies of Star Trek.