This is the ninth day of April and, I believe, the first issue of F&SF under the editorship of Sheree Renée Thomas. I know little about her, but since she’s only the second female editor of F&SF (the first being my friend Kristine Kathryn Rusch), I expect her to bring a whole new sensibility to what may be my favourite “newcomer” SFnal magazine. (Amazing Stories, of course, is the “old man” of the SFnal magazine universe.) Oh, and by the way, Happy Spring to you all!

Let’s start off with a poem: “Transcendent City,” by Akua Lezli Hope, who is a West Indies descendent living in New York City. A non-rhyming poem, it is to my eyes very much a little firework of a paean to that city; its twenty-two scant lines sing a song about the present and the future of a vibrant and alive conglomeration of massive steel juggurnauts of towers intermixed with vibrant greens, “trees grow in air,” and humanity is poised to leap into the future. Nicely written!

“Crazy Beautiful” by Cat Rambo is the cover story. It’s about art, or maybe about the concept of art—visiual art, that is. In this world, the first two AIs come into being because IBM’s “Watson” communicates with a “sibling,” Ross. Then AIs become ubiquitous enough that a company buys and repurposes a medical AI—designed for biomodification—that had been abandoned by its parent company, and attempts to make it into an “art” AI by feeding it all they can about art (graphic art, not literary or musical) and art criticism, as well as “gene art.” But the AI disguises itself on the internet and starts not only learning about art, but also discussing art and attempting to influence people’s ideas about art. “Art, like information, wants to be free.” (A ubiquitous and somewhat fallacious argument used by many information pirates and “leakers.”)

So the AI, utilizing gene modification technology, attempts to make art “free” in the real world. I particularly like the concept of “sky whales”—congregations of floating or flying particles that group together so densely that they appear to be living animals in the sky, but can instantly regroup and appear to be something else. There are many fun ideas in this story, but I’m concerned by the repeated statement that “the subject died while in police custody.” I’m not sure how that all fits into the story… but I used to be in police work, so maybe I’m overly sensitive. Any road, as Bet on Pennyworth says, it’s an interesting story.

Morris Allen’s “Minstrel Boy Howling at the Moon” is by a guy who edits two oddly-named (online) magazines himself: Metaphorosis, and Vegan Science Fiction and Fantasy. Neither title is a typo, though I was unable to find a definition of “Metaphorosis.” Vegan SF/F is SF/F with “no meat, no hunting, and no riding horses.” (Obviously, the world is a stranger place than you or I ever imagined it would be.) As an editor, he’s obviously not unfamiliar with strange tales and good writing, because this story has both. Rafe (Rafael) has found himself more or less stranded in La Fave, Oklahoma, where he’s deputy assistant manager of the Lov’n’Stop Gas Station and bus stop. During the summers he finds himself setting fence posts to fill the empty gaps in his wallet—deputy ass’t mgr doesn’t use up all his time or pay very much—and his time. He’s taken up harmonica and is getting pretty good at it. Matt, his boss, is Caegu Native American, and doesn’t believe Rafe when Rafe says that occasionally his playing conjures up something like buffalo (or bison). But maybe his harmonica playing can get him out of the dust of La Fave and back into the big citiies, which might not be such a good thing. This story is so well written that I think it could make a pretty good short film.

“Our Peaceful Morning,” by Nick Wolven, is a silly science fantasy. It’s not a thing I can imagine happening and, for me at my center, SF/F stories have to have a core of reality (unless they’re pure fantasy). This one is all about a “treatment” that can be given to nonhuman animals to give them intelligence and voices. Which is fine, until you start saying mosquitos and worms can have the treatment. But it’s well written and amusing, sort of like a prose cartoon.

Akua Lezli Hope’s “Whale Talk” is a poem about whales and what their speech means. The general thrust here is that whales’ brains are much bigger than ours, and they’ve been around longer than homo sapiens, so they must be talking about deeper and bigger things, and when experienced directly (not through the protection of a submersible, for example) can change and heal a person. It’s a nice idea, but I don’t buy it; I don’t think whales and/or dolphins are intelligent in the way we understand intelligence. I’m sort of a cynic who recognizes wonderful, hopeful SFnal ideas, but doesn’t believe them. YMMV, however. (“Your Mileage May Vary.”)

“Speak to the Moon,” by Marie Brennan, is science fiction at first—then, pure fantasy—about Japan’s first manned moon mission, not by using any other country’s experts, expertise or equipment, but on their own—a point of national pride, and prideful also to the two astronauts in the lander. Kemuriyama is the male astronaut whose family fortune helped fund the mission; Itō the female, who resents that fact, which gives him the right to touch the moon’s surface first. But there are rituals to be observed first, to attract the moon’s kami. Itō understands and respects this; they are there to build a radio telescope; a task they accomplish together. Then, on the last day, the story drifts off into pure fantasy. Kemuriyama removes his suit on the surface and walks off, revealing himself to be an immortal from something like a thousand years in Japan’s past. He is attempting to fulfill a promise made to a long-dead Emperor. This story is so well researched, and so nicely written, that the switch to fantasy doesn’t bother me. The reason I call it fantasy rather than science fantasy is that although I’d personally love to be immortal, I don’t think immortality is possible. Entropy must, after all, have its way. But it’s such a good story (and I am, in many ways, a Nihonophile) that I enjoyed the heck out of it.

“In the Garden of Ibn Ghazi,” by Molly Tanzer, is apparently based on a card in a game called “Arkham Horror”; a game I’m unfamiliar with. This story plays with reality in a very Lovecraftian way. Many people these days decry H.P. Lovecraft’s stories because he was very much a racist; I’m not one of them—I read most of the Cthulhu Mythos stuff back in the ‘60s, and feel I’m quite capable of separating the writer from his works—and if you watched the TV show Lovecraft Country, which did a marvelous riff on Lovecraft’s own attitudes by making the protagonists black and the “bad guys” white, with a clever reimagining of shoggoths—you’d see that art can indeed stand apart from its creator. Anyway, I’ve been a big fan of Mythos stuff for decades. “In the Garden” is one of those “story within a story” things, where the author becomes part of the story. Although it’s based on a real game and, the author asserts, a real happening (she says she remembers reading a story with this story’s name, but no such story actually exists), it has a very dream-like quality that for me is too gentle to be “really” Lovecraftian. And the prose isn’t as purple as that I associate with the Mythos, but nonetheless, this is a well-done story that might get picked up and republished in some anthology.

Meg Elison’s “The Pizza Boy” is about a young man, Giuseppi Verdi, who makes and delivers pizza for a living. He lives in a ship, the Mehetabel, where he grows his own tomatoes, delivering the pizzas on some kind of scooter. Did I mention this is many years from now and not in our solar system and, incidentally, out in space? Well, it is. He’s independent, selling to Imperial Marine troops and anyone else who orders. He has to buy his salty green cheese from some nonhuman types who don’t speak his language, and although lots of people hope for mushrooms, they’re hard to find. His dad, who disappeared last year, used to buy shrooms from a group of hippies on some planet but who were wiped out during a clash between troops and rebels. He’s been alone since. (His mother was drafted by the Queen’s Armada, the QA, some years ago.)

He’s also a secret courier or spy, but since most spies who try to impersonate pizza boys don’t know the secret sauce recipes, or anything like what he knows, he’s unlikely to be busted. This is one of the unlikeliest SF stories I’ve read in a long time, but you know what? It works! You buy into the idea that hundreds (?) of years from now, out in space, someone will be making and delivering pizzas and, incidentally, working against the established order (the QA marines are brutes anyway. And they don’t tip).

And now we have “The Music of the Siphorophenes” by C. L. Polk, another pure-d SF story of the future. It’s a story about Reese, who sails the ship Red Wind to take tourists to Saturn and the Outers; it’s about Ansa, the biggest pop star in the Solar System; and it’s about Jodi (short for Jodianthaladan), who is a Siphorophene, a space-dwelling creature. Some of the Siphorophenes are two kilometers long, but Jodi’s a young one. It’s also a story about piracy, and death, loss, and the forming of a new family, a “we” for the three. A very nice story, and well written.

Harry Turtledove’s new story is called “Character,” a “loving tribute” to a living writer, Peter S. Beagle, who, if you don’t know him, is a really nice guy; someone I wish I knew better. But my acquaintance is slight, alas. Turtledove is best known for writing excellent alternate-history books and stories, but this isn’t one of them—at least at the start. The protagonist of this story is a character in someone else’s story, going by the name of Steve (he only learns it when another character speaks it). Steve hates the way he gets yanked around, and when he’s made to buy a copy of Beagle’s The Folk of the Air in a used bookstore, he learns what a crappy writer his author is compared to Peter. He reads The Folk of the Air, and likes a character called The Ronin Benkei. Which is good, because his author decides to make him into Benkei.

Now, all of a sudden—characters hate when authors change stuff without warning—he’s Benkei, a samurai in medieval Japan. At first, Benkei is quoting lines from things like the Bible, and the movie Titanic, but the author does some rewrites and soon Benkei is working for another Ronin (wandering samurai for hire) and having adventures—and getting older. It’s an interesting life, even if this writer isn’t Peter B., right up until it ends. (But don’t worry, he’s a character… he’ll be back). An interesting story.

“Jack-in-the-Box” is by Robin Furth. It’s a story (just post-WWII) about an American woman, Mrs. Benjamin, whose British husband is off in the Army; she visits a large estate while writing an article for Country Life magazine about the Blackthorn family. The squire, Lord Blackthorn, has recently died, but his son and grandson (who will inherit the title and the estate) are still living in the home. Gradually, as she witnesses the interaction of Philip Brandston-Smith and his son Jack Blackthorn, she realizes that something is, as Shakespeare said, rotten in Denmark. There is clearly no love lost between the two; and as she sits in the late Lord’s den going through his papers, she finds that he was a brilliant, if somewhat twisted, surgeon. And the grandson and his father clearly despise each other. I haven’t read any Henry James in years, but this kind of reminded me of him. A genre story that cleverly skirts the genre, only hinting at it here and there.

“The Bletted Woman” is Rebecca Campbell’s newest story for F&SF. “Bletting” is a process of allowing a medlar to become overripe—nearly rotten—so that the starches inside convert to sugar and the fruit becomes suitable for eating or making into jelly. (A medlar is, and looks, similar to a rose hip; in fact, it’s related to a rose.) It’s a horror story of sorts; it takes place in a world similar to this, only that world’s decay is far advanced over ours (we’re catching up, though). Judith’s husband, Ben, succumbed to age and Alzheimer’s, as had her mother; and when she receives her own diagnosis, Judith sets about changing her life and routine to minimize the disruptions caused by loss of memory. But soon a woman from the Institute for Advanced Study comes to tell her there may be a process that will give her something resembling life after death. Judith understands; she says we’re all something’s afterlife—we were all once something else, an earthworm, a chicken, a cow, only we don’t remember it. There is an afterlife, but it’s not personal, she says. They tell her they can give her a personal afterlife.

She goes to an island owned by the Institute and learns that the dead can communicate in the same way trees communicate through root systems; the researchers just haven’t learned to decode the communication. Judith agrees to help, to become one of the “rooted dead,” and perhaps to facilitate communication. It works out, but not in the way the researchers expect. It’s kind of a morbid little tale. However, I have to disagree with the statement that trees “communicate”—certainly they exchange something through their root systems, but to call it communication is, in my opinion, stretching a point. That leads to M. Night Shyamalan’s The Happening, where the trees all agree to kill off humanity because of their anti-tree transgressions. But the story’s well done, even if I can’t agree with it.

And the last story in this issue is “Mannikin,” by Madeleine E. Robins. It’s a fable, set in a land ruled by a gerent, whose army is always greedy for men because of the wars the gerent is constantly fighting. Taba’s husband was conscripted and killed in one of those wars, leaving her pregnant and alone. When Bijan is born, Taba swears he will never die as her husband did, and goes to the local witch, who puts a spell on him to make him appear female: as long as the clay mannikin Taba wears between her breasts is intact, he will appear female. Bijan is raised as Bira, and never knows she is actually a he. They live in the walled city of Mekaon, the district capital.

When the gerent overreaches himself, his army is defeated, and the iotrun comes to Mekaon; all the men of Mekaon save the very young, the very old, and the wounded are gone, and Bira leads the women in defending the city. She is told by the river goddess that she must use “women’s weapons” to defeat the iotrun, and Bira goes to treat with him for the city’s safety. What happens then is something I’ll leave you all to discover; this is so nicely written that I don’t want to spoil it. I enjoyed this one; and I can’t say I found anything to make it less enjoyable.

Of course, the issue contains all the usual stuff: an editorial by Sheree Renée Thomas; book reviews by Charles de Lint and Michelle West; an article on television by David J. Skal; a science column by Jerry Oltion; a “curiousities” (sic) column by Joachim Boaz; and an article on SF&F (&H) publishing by Arley Sorg. And cartoons by Arthur Masear, Nick Downes, Bill Long, Kendra Allenby, and Mark Heath. A full issue indeed!

I know this sounds weird, but whenever I write “XXX is a story by xxx,” I always want to say “It’s a dirty story of a dirty man and his clinging wife doesn’t understand…” Just one of my little foibles, I guess. (In case you haven’t guessed, that line is from The Beatles’ “Paperback Writer.”)

I was given a review from a newspaper (I think the Skagit Valley Herald), by my brother- and sister-in-law for the 2020 film Freaky, with Vince Vaughn. They thought it was worth watching.

It’s a riff on the 1976 film Freaky Friday, with Jodie Foster, where she switches bodies with her mother. The latter was successful enough that it was remade several times; lastly with Jamie Lee Curtis and Lindsay “Can’t Stay Out of Rehab” Lohan. It was an okay concept and, if you’re short of concepts, probably due for a reimagining. Christopher Landon, who has written some halfway decent scripts, including several Paranormal Activity sequels and Happy Death Day and Happy Death Day 2U, decided he was the one to reimagine it. He apparently decided to make it a comedy-horror riff on slasher movies like Friday the 13th. (And in case you didn’t get it, the movie opens with the title “Wednesday the 11th”… subtle, eh?)

Anyway, the review, from Katie Walsh of the Tribune News Service, raves about Vaughn’s performance as a large, older male body inhabited by a bullied teen-age girl (although Walsh only gave the movie three stars out of a possible five). Quick précis of the plot: Millie (Kathryn Newton, mostly known for TV roles) is a bullied teen who’s got eyes for one of the Blissfield Beavers football players. Her dad is dead; her mom drinks herself into a stupor every day; and her best friends are also school outcasts: a black girl (Nyla, played by Celeste O’Connor) and a gay young man (Josh, nicely understated by Misha Osherovich). The McGuffin here is an Aztec dagger called “La Dola” which, when stabbed into Millie by the Blissfield Butcher (Vince Vaughn) at night, causes them to switch bodies. Hilarity ensues when an Aztec pyramid appears and they both get bloody shoulders. (Well, no, it doesn’t. Much of the comedy in this movie is kind of lame, IMO. An example is when Millie—in Butcher’s body—is sitting in a washroom stall reading the rather explicit graffiti on the wall and sees a line that says “Millie Kessler gobbles cock,” with a crude drawing of a girl’s face and a set of large male genitalia approaching it. Whoa, hilarious!) Another is when she disposes of the shop teacher who’s been bullying her all year (Alan Ruck, who you may remember as Ferris Bueller’s best friend) in a very graphic death scene.

The best thing about this movie is the various understated performances, like Vaughn as Millie; at his best, he’s very good at channeling someone he’s not (like his wannabe black pimp in Be Cool); Osherovich’s Josh, as mentioned before; and Newton playing both a bullied petite blonde teen and a deranged killer trapped in a bullied blonde teen. If it weren’t for those three, the movie wouldn’t deserve more than three out of ten stars. I, personally, would give it five, based on those actors.

The reason Vaughn’s performance is the highlight of the movie is, frankly, that the movie is a very uneven homage to teen slashers like the aforementioned Friday films plus a couple of nods to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and others of the genre. The problem is that where it’s “horror” it’s over-the-top slasher horror (graphically speaking, with lots of gore); where it’s comedy, it’s somewhat weak comedy. And some of the comedy is of the “new norm” type with overt bathroom and sexual imagery and jokes that frankly, to an older viewer, fall extremely flat. Hey, I get it: to the intended audience it’s all very new and funny. I think the difference is that older people prefer subtle to overt; when I was a kid I really, really wanted to see explicit death and destruction (and yes, sexuality) in the movies. So there you go; it’s experience that makes the “overt” less desirable. The movie will be enjoyed more by the younger, I think.

A side note here: I’m not a football fan; in fact I never heard of Aaron Rodgers until he became the Jeopardy guest host for this week and next week. But at one point in this movie, Vaughn is asked to disguise himself with a rubber mask of… you guessed it: Aaron Rodgers. Some coincidence!

Please remember that when I write a film (or even a book or TV) review, what I’m expressing is only my opinion. I don’t claim to be a critic in the usual sense; I’m not expressing a universal truth about anything—I’m not qualified to dispense universal truths. You may have an entirely different opinion of that thing I review, and you are certainly allowed to do so. I’m no kind of arbiter of what’s good and what’s bad. I’m just very opinionated.

If you liked my column—or even if you disliked it—comments are welcome. All your comments, good or bad, positive or negative, will be read and thought about. (Be polite, though. I may not agree with your comment, but I will try to respond.) My opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owner, editor, publisher or other columnists. See you next time!

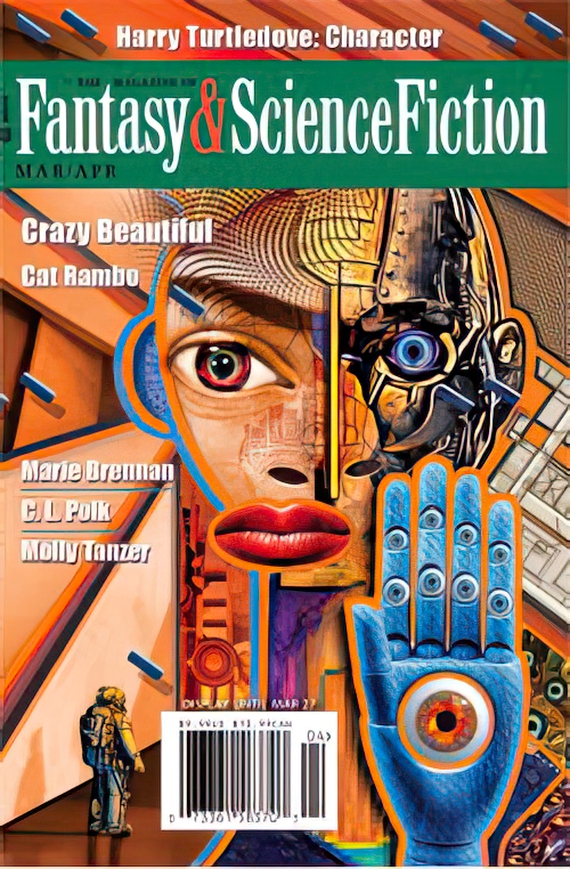

Seems like a bonus issue, with some really good stories in it. I liked the Picasso-like cover.

John, it’s amazing (no pun intended) that F&SF has managed to maintain a high rate of excellent stories over the years.