Do you remember where you were when you first read Ringworld?

In my personal case, I was in a Walden’s Books Store at my local mall, having biked over with allowance, birthday money or saved lunch money to make my (near daily) purchases in the newly branded Science Fiction and Fantasy section. It was 1971 or 1972 and Ringworld had just won the Hugo Award for Best Novel.

I got this edition -(though sadly,not a first printing: we would eventually come to learn that the Earth rotated in the wrong direction in that edition, but was quickly corrected for the next printing).

And a heck of a Best Novel it was, too.

Firmly ensconced within the “Big Dumb Object” trope, the Ringworld was a technological construct, a world built as a ring around its star, approximately 1 AU in radius, spinning so that gravity on the inner surface is approximately 1 G, a series of gigantic rectangles orbiting closer to the sun creating an artificial day and night cycle.

Ringworld also introduced me to Niven’s “Known Space” background and, eventually, a comprehensive history of the future, similar to (and in many respects more detailed than) Robert Heinlein’s “Future History”.

Niven’s future, a Hard Science Fiction construct, has had a tremendous influence on the field; he peopled it with unique societies within Sol system: Belters – the quintessential Space Libertarians (miners flying individual singleships through the asteroid belt, seeking metals and monopoles, risking lonely death in pursuit of great riches), Goldskins – UN Space Police, far flung stellar colonies often established on less than ideal worlds (long range space probes were programmed less discriminately than they should have been); a pantheon of unique and deeply complex alien species, from ancient Slaver races preserved by stasis fields to the master genetic manipulators, the Pierson’s Puppeteers; Kzinti, a fierce cat like warrior species that would find its way into Star Trek; Kdatylno, sculptors who see via radar, dolphins and all manner of human sub-species.

Niven’s future, a Hard Science Fiction construct, has had a tremendous influence on the field; he peopled it with unique societies within Sol system: Belters – the quintessential Space Libertarians (miners flying individual singleships through the asteroid belt, seeking metals and monopoles, risking lonely death in pursuit of great riches), Goldskins – UN Space Police, far flung stellar colonies often established on less than ideal worlds (long range space probes were programmed less discriminately than they should have been); a pantheon of unique and deeply complex alien species, from ancient Slaver races preserved by stasis fields to the master genetic manipulators, the Pierson’s Puppeteers; Kzinti, a fierce cat like warrior species that would find its way into Star Trek; Kdatylno, sculptors who see via radar, dolphins and all manner of human sub-species.

Niven equipped this future with an equally astonishing array of technologies, from Bussard Ramjets (magnetic fields  compress interstellar hydrogen and burn it as fuel for a fusion reactor) to Autodocs, Communications lasers that can serve as weapons, Stage Trees (biological solid rocket boosters), flycycles (can anyone say “I saw those in Star Wars”?), organbanks and organ replacement technology, drug addiction via direct stimulation of the brain’s pleasure center, spaceships constructed as a single molecule, instant transfer booths (and later, stepping discs)…

compress interstellar hydrogen and burn it as fuel for a fusion reactor) to Autodocs, Communications lasers that can serve as weapons, Stage Trees (biological solid rocket boosters), flycycles (can anyone say “I saw those in Star Wars”?), organbanks and organ replacement technology, drug addiction via direct stimulation of the brain’s pleasure center, spaceships constructed as a single molecule, instant transfer booths (and later, stepping discs)…

And he created numerous unique characters, both human and alien – Teela Brown, the luckiest girl in the universe, Beowulf Schaeffer who survived a trip to the center of the galaxy; Nessus, the “Mad” Puppeteer, quasi ambassador to human space, qualified for that duty owing to mental illness; Speaker-to-Animals, the Kzinti Warrior who earns the right to his name on a trip to the Ringworld (“animals” referring to other sentient species); Gil, “the Arm” Hamilton, a cop with “something extra”.

Larry also wrote non-canon stories, frequently with other authors. A favorite was Jerry Pournelle, with whom he wrote a number of best sellers – Lucifer’s Hammer (one of, if not ‘the’ best tales of a near extinction-level encounter with a comet); Footfall (a somewhat fraught alien invasion novel: the aliens look like nothing so much as baby elephants with two trunks and wearing platform shoes…it helps to know that there had supposedly been a falling out between the authors and their publisher over completing contract work) and, of course, the novel that Robert Heinlein would write was “…possibly the best contact-with-aliens story ever written…” – The Mote in God’s Eye.

Larry also wrote non-canon stories, frequently with other authors. A favorite was Jerry Pournelle, with whom he wrote a number of best sellers – Lucifer’s Hammer (one of, if not ‘the’ best tales of a near extinction-level encounter with a comet); Footfall (a somewhat fraught alien invasion novel: the aliens look like nothing so much as baby elephants with two trunks and wearing platform shoes…it helps to know that there had supposedly been a falling out between the authors and their publisher over completing contract work) and, of course, the novel that Robert Heinlein would write was “…possibly the best contact-with-aliens story ever written…” – The Mote in God’s Eye.

He dabbled in “magic”, co-authoring one of my favorite quasi-SF comedies with David Gerrold – The Flying Sorcerers – which, like Footfall, featured numerous other science fiction authors as characters; with Steven Barnes he wrote the  Dreampark series (an RPGer’s dream amusement park) and dabbled in fantasy with numerous stories based on the concept that “magic” is a technology subject to the laws of thermodynamics, helping to introduce a more rigid world-building conceptualization to epic fantasy. His Man-Kzin Wars shared universe series created an outlet for military science fiction featuring the antics of a species that were fierce, honorable warriors, flawed only by their tendency to attack before being truly ready to do so. (How do you issue a challenge to a Kzin? You scream, and then you leap.)

Dreampark series (an RPGer’s dream amusement park) and dabbled in fantasy with numerous stories based on the concept that “magic” is a technology subject to the laws of thermodynamics, helping to introduce a more rigid world-building conceptualization to epic fantasy. His Man-Kzin Wars shared universe series created an outlet for military science fiction featuring the antics of a species that were fierce, honorable warriors, flawed only by their tendency to attack before being truly ready to do so. (How do you issue a challenge to a Kzin? You scream, and then you leap.)

Niven’s DNA can be found throughout the field of science fiction, often so deeply embedded that new generations of readers sometimes find his work seemingly derivative, believing, for example, that he got the idea for Ringworld from the HALO series of games, when, in fact, the exact opposite is true. (Ringworld, published 1970; HALO produced 2001.)

You can see his influence in television series like The Expanse, The Outer Limits episodes, Star Trek, the Animated Series (introduction of the Kzinti to the Star Trek canon); in games, like the aforementioned HALO; earlier RPGs based on Ringworld and Known Space, and

You can see his influence in television series like The Expanse, The Outer Limits episodes, Star Trek, the Animated Series (introduction of the Kzinti to the Star Trek canon); in games, like the aforementioned HALO; earlier RPGs based on Ringworld and Known Space, and

on fellow authors and fans: Niven championed getting the science right and often led discussions among fans and fellow authors that would work out various technologies later to be incorporated into various stories; The Ringworld Engineers sequel is based on the research of fans who determined that without some stabilizing mechanism, the Ringworld would wobble and eventually impact its sun. (That right there is a near-perfect example of one of the things that makes Science Fiction Fandom unique.)

Several years ago (2012) saw the publication of the last of the Fleet of Worlds series, a series written with author Edward  Lerner, essentially a prequel series to Ringworld. Ringworld itself takes place within the Known Space continuum. Essentially, humanity has moved into space, established several extra-solar colonies, enjoys long life owing to drugs and organ-replacement technology and has benefited by trading for advanced technologies with Pierson’s Puppeteers, a far more advanced, yet seemingly benevolent, species, who suddenly disappear from all of known space. Except for Nessus, former representative to humanity, who seeks out an oddball crew to investigate an anomaly in deep space – the Ringworld.

Lerner, essentially a prequel series to Ringworld. Ringworld itself takes place within the Known Space continuum. Essentially, humanity has moved into space, established several extra-solar colonies, enjoys long life owing to drugs and organ-replacement technology and has benefited by trading for advanced technologies with Pierson’s Puppeteers, a far more advanced, yet seemingly benevolent, species, who suddenly disappear from all of known space. Except for Nessus, former representative to humanity, who seeks out an oddball crew to investigate an anomaly in deep space – the Ringworld.

The initial series:

Ringworld (1970)

The Ringworld Engineers (1979)

The Ringworld Throne (1996)

Ringworld’s Children (2004)

Fate of Worlds (2012) (with Edward M Lerner)*

The “Prequel” series:

The “Prequel” series:

Fleet of Worlds (2007)

Juggler of Worlds (2008)

Destroyer of Worlds (2009)

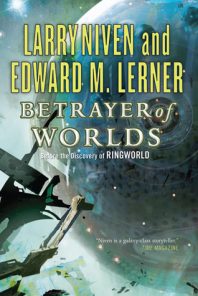

Betrayer of Worlds (2010)

*Fate of Worlds is considered to be the conclusion of both series)

Niven’s latest work, written with Gregory Benford, The Bowl of Heaven series, introduces another BDO; some have described it as a revisiting of Ringworld.

Niven seems to have fallen out of favor so far as popular discussion goes these days; this I attribute to his having run afoul of the culture wars within the science fiction field, but be that as it may, we’re discussing the works and his influence on the field here, not his supposed politics. You practically can’t touch a Hard SF work without stumbling across  something that is probably Niven-inspired.

something that is probably Niven-inspired.

You can find out more about Known Space, its future history, the author himself, at the following links:

History Timeline (and more, including an article by yours truly)

Science Fiction Encyclopedia entry

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.