The void of space. A who’s-who of celestial bodies can be seen against the dark-blue firmament: the crater-scarred surface of Earth’s moon; the glow of the sun, tucked away in the bottom corner; the ringed planet Saturn; a ruddy-hued orb that may be Mars or Venus. Dominating the scene is a spacecraft. Not all of it is visible, but we can see enough to discern that it resembles a submarine in design, complete with a line of port holes along the side. The inhabitants of the ship are doubtless gazing out upon the scattered planets, just as we are as we look upon the illustration.

The void of space. A who’s-who of celestial bodies can be seen against the dark-blue firmament: the crater-scarred surface of Earth’s moon; the glow of the sun, tucked away in the bottom corner; the ringed planet Saturn; a ruddy-hued orb that may be Mars or Venus. Dominating the scene is a spacecraft. Not all of it is visible, but we can see enough to discern that it resembles a submarine in design, complete with a line of port holes along the side. The inhabitants of the ship are doubtless gazing out upon the scattered planets, just as we are as we look upon the illustration.

The March 1930 issue of Astounding Stories was on the newsstands, marking the third instalment of this pulp fiction pioneer.

Established readers of the series would have recognised the names of two contributors, Captain S. P. Meek and Ray Cummings, each of whom had previously written stories for Astounding. But other than them, the issue was a round-up of new talent for the magazine. Together, the contributors explored new worlds just as surely as the crew of the spacecraft on the cover…

“Cold Light” by Captain S. P. Meek

In what was by now a regular feature in the magazine, Captain S. P. Meek provides another tale about scientific investigator Dr. Bird and his Watson-alike Carnes.

In what was by now a regular feature in the magazine, Captain S. P. Meek provides another tale about scientific investigator Dr. Bird and his Watson-alike Carnes.

The story begins with Carnes calling Dr. Bird over to investigate another mystery. While flying, Carnes witnessed the crash of a plane carrying valuable cargo – the plane breaking to pieces on the ground but strangely failing to burst into flame. Flying to the scene of the disaster, Carnes and his pilot Hughes felt an inexplicable coldness above the crashed plane; then, looking at the wreckage through binoculars, they noticed the weird state of the victims: “the bodies of the crew had broken into pieces, as though they had been made of glass. Arms and legs were detached from the torsos and lying at a distance. There was no sign of blood on the ground.”

Dr. Bird investigates the crash, and attributes the disaster to the plane running into a belt of cold that froze it and its occupants solid. But he acknowledges that this would take an extremely low temperature: “It was no ordinary cold. Carnes; it was cold of the type that infests interstellar space; cold beyond any conception you have of cold, cold near the range of the absolute zero of temperature, nearly four hundred and fifty degrees below zero on the Fahrenheit scale.”

What could have created this cold belt? Given that the plane’s valuable cargo had been taken from the wreckage, Dr. Bird speculates that the coldness was created artificially in a deliberate attempt to bring down the plane. The doctor produces an elaborate device (“Merely a thermocouple attached to a D’Arsonval galvanometer”) and uses it to trace the origin of the cold belt.

Eventually Bird, Carnes and their two guides come to a ramshackle building attached to a vast apparatus – a projector of some sort. As they approach, they are accosted with a ray of deadly cold, which they disable by shooting out the projector. Following a gunfight, the heroes meet the brain of the operation, who divulges the basis of his scientific theories before expiring: “In the course of my experimental work, I had discovered that cold was negative heat and reacted to the laws which governed heat… as heat, positive heat is a concomitant of ordinary light, I have found that cold, negative heat, is a concomitant of cold light.”

“Cold Light” is a solid addition of the subgenre of science fiction detective stories. Its central scientific concept is hard to take too seriously, but the story sticks to its own internal logic closely enough to work.

Brigands of the Moon by Ray Cummings (part 1 of 4)

After an introduction in which author Ray Cummings muses about what George Washington would have made of a novel depicting everyday life in 1930, Astounding’s second novel-length work takes us to the year 2079. Here we meet hero Gregg Haljan, crewmember of a ship called the Planetara that carries passengers and mail between Earth, Mars and Venus

Gregg’s friend Johnny Grantline is in charge of a lunar expedition: although the moon is uninhabited and seldom visited, rumours persist of vast mineral wealth in the form of radium. Grantline’s expedition was supposed to be a secret, but word has somehow gotten out. “Outside, anywhere outside these walls, an eavesdropping ray may be upon us”, the ship’s captain Carter says to Gregg. “You know that? One may never even dare whisper since that accursed ray was developed.”

Carter, as it happens, already has a possible culprit in mind. He warns Gregg about George Prince, a mechanical engineer of the Earth Federated Radium Corporation who is “known now as unusually friendly with several Martians in New York of bad reputation”.

While on board, Gregg and his pal Dan “Snap” Dean find themselves surrounded with intriguing characters. Rance Rankin is an American stage magician – although a Venusian girl named Venza, who works in a theatre, considers him a fraud. Sero Ob Han, another denizen of Venus, is “preaching the religion of the Venus Mystics”, leading to a religious dispute with English traveller Sir Arthur Coniston. With a prowler on board, any one of these people could be a suspect:

I could not help noticing Sir Arthur Coniston’s queer look, and I think I have never seen so keen a glance as Rance Rankin shot at me. Were all these people aware of Grantline’s treasure on the moon? It suddenly seemed so.

Then we have prime suspect George Prince and his sister Anita. Gregg finds himself falling in love with the latter: “The starlight was mirrored in her dark eyes. Misty eyes, with great reaches of unfathomable space in their depths. Yet I felt their tenderness.” Indeed, he even finds himself warming towards her brother, despite the captain’s warning: “And for half an hour I chatted with George Prince. He seemed a gay, pleasant young man. I could almost have fancied I liked him. Or was it because he was Anita’s brother?”

Also on board are two Martian siblings, Set Miko and Setta Moa (“Set” and “Setta” being the Martian equivalents of Mr and Mrs, Cummings explains). Gregg finds Moa appealing (“Her limbs were encased in pseudo-mail. She looked, as all Martians like to look, a very warlike Amazon. But she was a pretty girl. She smiled at me with a keen-eyed, direct gaze”) but Miko soon turns out to be a shady character.

After incidents involving stolen passwords, a near-miss with an asteroid and the magnetic force of the ship’s artificial gravity-controls being tampered with (“Snap was in advance of me. His body suddenly rose in the air. He went like a balloon to the ceiling, struck it gently, and all in a heap came floating down and landed on the floor!”) disaster strikes. Miko – by this point established as the main villain, albeit one working with co-conspirators on board – shoots Anita with a heat ray. Gregg is forced to watch a space funeral for his beloved:

They tied the shroud over her face. I did not see them as they put her body in the tube, sent it through the exhaust chamber, and dropped it. But a moment later I saw it—a small black oblong bundle hovering beside us. It was perhaps a hundred feet away, circling us. Held by the Planetara’s bulk, it had momentarily become our satellite. It swung around us like a moon. Gruesome satellite, by nature’s laws forever to follow use told us before she died.

But the heroes receive unexpected aid from Gregg Prince, who turns out to be something of a double agent, working for Miko but willing to betray the villainous Martian (indeed, the heat ray that hit Anita was actually aimed at George). By eavesdropping on Miko and his collaborators, the heroes are able to learn more about his operations. Eventually a fight breaks out across the ship, Miko and his conspirators against the innocent crew and passengers.

While still an adventure yarn at heart rather than anything cerebral, Brigands of the Moon has so far made considerably better use of its science fictional concepts than Cummings’ first story for Astounding, “Phantoms of Reality”. Early on, the characters use a sort of disc-stored hologram (“The image glowed on the grids before us. His name. George Prince, in letters illumined upon his forehead, showed for a moment and then faded. He stood smiling sourly before us as he repeated the official formula…”). We later see rays being used to detect radioactive ore on the moon: “The receiving shield was glowing a trifle! Gamma rays were bombarding it! It glowed, gleamed phosphorescent, and the audible recorder began sounding its tiny tinkling murmurs.”

Another memorable scene involves the craft’s near encounter with the asteroid, which turns out to have an entire ecosystem on its surface (“There seemed a normal atmosphere. We could see areas where the surface was obscured by clouds. And oceans, and land masses. Polar icecaps. Lush vegetation at its equator. Blackstone had roughly cast its orbital elements. A narrow eclipse. No wonder we had never encountered this fair little world before. It had come from the outer region beyond Neptune.”) The space opera genre was still in its infancy at this point, but so many of its key elements can already be seen in the first quarter of Brigands of the Moon.

Cummings’ fertile imagination carries him into the instalment’s all-action climax, where heroes and villains alike have various gizmos at their disposal. The sinister Miko has an “electronised metallic robe” that makes him invisible and burns those who try to apprehend him; the heroes also have to tangle with a “Martian paralyzing ray” and low-gravity fisticuffs (“Grotesque, abnormal combat! Like fighting in weightless water”). The first instalment ends just as Gregg learns that his beloved Anita may not be as dead as he had been led to believe.

“The Soul Master” by Will Smith and R. J. Robbins

Hard-edged reporter Horace Perry and neophyte photographer Skip Handlon are sent to meet Professor Anton Kell, a reclusive scientist who has been carrying out strange experiments in a rural backwoods. Following the professor’s trail, the pair come across reports that he was involved in an experiment that left a bull barking and eating meat like a dog, and was also questioned by authorities over the disappearance of local man Robert Manion and his daughter.

The reporters come to the professor’s property, and see the fruits of his labours. These include a large wolf-hound that acts like a sheep, and a badly-bruised mule that imitates a parrot:

With something between a curse and a sob, the mule lunged at its crib as if attempting to get bodily into it. But no: it was only trying to perch on its edge. Now it had succeeded. The ungainly beast hung there a second, two, three. From its uplifted throat issued that usually innocuous phrase, a phrase now a thing of delirious horror:

“Pretty Polly!”

Finally, they meet Professor Kell himself, who tries to drive them away with a blunderbuss; only when Perry threatens him with bad press does he invite them into his laboratory. After they take in their surroundings (“The average imagination would instantly pronounce it the abode of a maniac, or the lair of an alchemist”) the professor hands the two newspapermen cigars – which turn out to be drugged. When Perry comes to, he is on board a train heading back to his hometown, with Handlon nowhere to be seen.

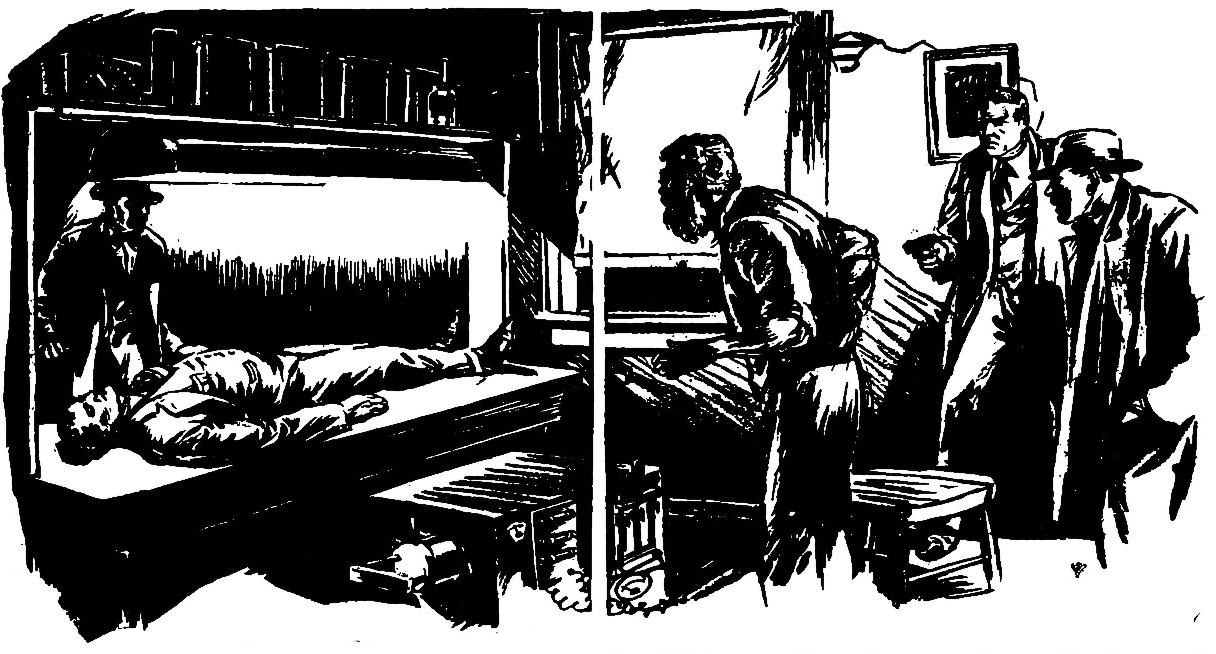

Hearing what happened, Perry’s editor sends another reporter – Jimmie O’Hara – to search for the missing Handlon. O’Hara reaches the residence of Professor Kell, and sees the professor carting around and dismembering a human corpse. The reporter deduces that he is too late to save either Handlon or the other missing man, Robert Manion, but he at least stands a chance of rescuing Manion’s daughter Norma, who is bound and gagged in the building. O’Hara then manages to overpower the professor, just in time for his newspaper colleagues and a team of plainclothes police to turn up.

The group force the professor to reveal the fate of Handlon, and he makes a bizarre confession: Handlon and Perry are sharing the same body. “I have been working for years on my system of deastralization”, he explains. “This last year I at length perfected my electric de-astralizer, which amplifies and exerts the fifth influence of de-cohesion.” He used this to swap the minds of animals, prior to his experiments on the two reporters: “I found it was possible to make two astrals exchange bodies. Bat I also wanted to see if it were possible to cause two astrals to occupy the same body at the same time, and if so what the result would be. I found out.”

Handlon’s body having been destroyed, the professor suggests that Norma be used as the new host for the photographer’s mind. O’Hara, appalled by this idea, instead arranges for Hanlon’s astral to be placed into the professor’s body. This leads to a scene in which the two men’s astral forms take part in a visible fight:

A cry of consternation from the detective aroused Jimmie. Skip Handlon’s astral had appeared within the field of the nebula to fight for possession. There ensued what was perhaps the weirdest encounter ever witnessed. Though he was in poor physical shape, the Professor seemed to have an extremely powerful astral; and for some time the spectators despaired of Handlon’s victory.

But Hanlon’s astral is successful. After some comic-relief encounters with a couple of the professor’s less imposing creations (a parrot with the temperament of a mule and a snake that meows) Hanlon is ready to start a new life in his appropriated frame, while the heroes set fire to the building to destroy all trace of the professor’s villainy.

“The Soul Master” initially feels like a compressed re-write of H. G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau, but turns out to be a body-swap story (a genre already covered by Astounding with M. L. Staley’s “The Stolen Mind”). It does a fairly good job of summing up both the strengths and weaknesses of the burgeoning pulp science fiction field: on the one hand it delivers enough eerie, tense atmosphere and dastardly villainy to provide entertainment value, on the other hand it has little room to explore the implications of its central concepts in the way that a writer like Wells might have done. Author Will Smith had previously penned four stories for Weird Tales, two with his present writing partner R. J. Robbins, but the duo appear to have subsequently vanished from the world of speculative fiction.

“From the Ocean’s Depths” by Sewell Peaslee Wright

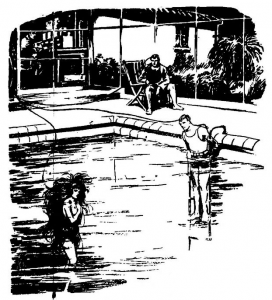

Protagonist Taylor gets an invitation from his inventor friend Warren Mercer, and heads over to Mercer’s home-cum-laboratory. There, at the bottom of a pool, Mercer shows him the “strangely graceful figure of a girl”, “nude save for a great mass of tawny hair that fell about her like a silken mantle”. Taylor initially takes the submerged figure to be a porcelain statue, until he notices her striding through the water towards him “with a grace of movement comparable only with the slow soaring of a gull”.

Protagonist Taylor gets an invitation from his inventor friend Warren Mercer, and heads over to Mercer’s home-cum-laboratory. There, at the bottom of a pool, Mercer shows him the “strangely graceful figure of a girl”, “nude save for a great mass of tawny hair that fell about her like a silken mantle”. Taylor initially takes the submerged figure to be a porcelain statue, until he notices her striding through the water towards him “with a grace of movement comparable only with the slow soaring of a gull”.

Yet all the while she remains below the surface, breathing water. Taylor finds the spectacle unnerving: “There was nothing sinister in the gaze, yet I felt my body shaking as though in the grip of a terrible fear. I tried to look away, and found myself unable to move.”

Mercer explains that he found the girl during a trip to a beach, where he came across her face-down in water. He took her home in an effort to help her, only for her to retreat into his pool – and then to fly into a fury if either Mercer or his assistant Carson enters the water with her. However, the girl takes a liking to Taylor, apparently because his pale complexion and white bathing costume mirror her own skin tone, and so Mercer has chosen him to make communication with her.

Although the girl appears to speak no language, the inventor – fortuity itself! – has a “thought-telegraph” at his disposal, a head-mounted electric gadget that allows the transmission of mental words and images. And so, Taylor gets up close and personal with the huge-eyed, web-fingered girl, using the thought-telegraph to receive pictures of her life beneath the sea. He sees the girl living amongst igloo-like structures of coral with the rest of her kind, venturing out past various shipwrecks, fending off a shark using a knife only to fall and hit her head, causing her to float to the surface where she was found by Mercer.

The visions touch upon an ancestral memory within Taylor’s mind, and the encounter takes a physical turn: “I remembered only that a note had been sounded that awoke an echo of a long-forgotten instinct I think I kissed her.” Taylor pulls away after this incident, but Mercer pressures him to continue. He sees the girl’s memories of her childhood, when an undersea elder told her stories of the surface world. This leads to Taylor seeing the aquatic race’s ancestors as they break apart from the rest of prehistoric humanity to return to the sea. Finally, the girl pleads to be reunited with her family.

After returning the girl to her element, the two men discuss her origins:

“Man came up from, the sea,” he said slowly, “and some men went back to it. They were forced back to the teeming source from whence they cane, for lack of food. You saw that, Taylor—saw her forebears become amphibian, like the now extinct Dipneuste and Ganoideil, or the still existing Neoceratodus, Polypterus and Amia. Then their lungs became, in effect, gills, and they lost their power of breathing atmospheric air, and could use only air dissolved in water.

“A whole people there beneath the waves that land-man never dreamed of—except, perhaps, the sailors of olden days, with their idea of mermaids, which we are accustomed to laugh at in our wisdom!”

“From the Ocean’s Depths” offers two science fiction concepts for the price of one, with the aquatic splinter-race of humanity joined by a thought-transference machine. Sewell Peaslee Wright comes up with a fairly thin narrative for them, the story boiling down to a routine noble-savage-girl fantasy, but it has its share of imaginative touches. A good example is the scene in which Taylor witnesses the aquatic race’s land-dwelling ancestors, not as they existed but as the amphibian girl imagined them existing: their jungle home looking oddly like seaweed, fire rendered only as a flickering red spot. A sequel to the story, “Into the Ocean’s Depths”, was published in the May 1930 issue of Astounding.

“Vandals of the Stars” by A. T. Locke

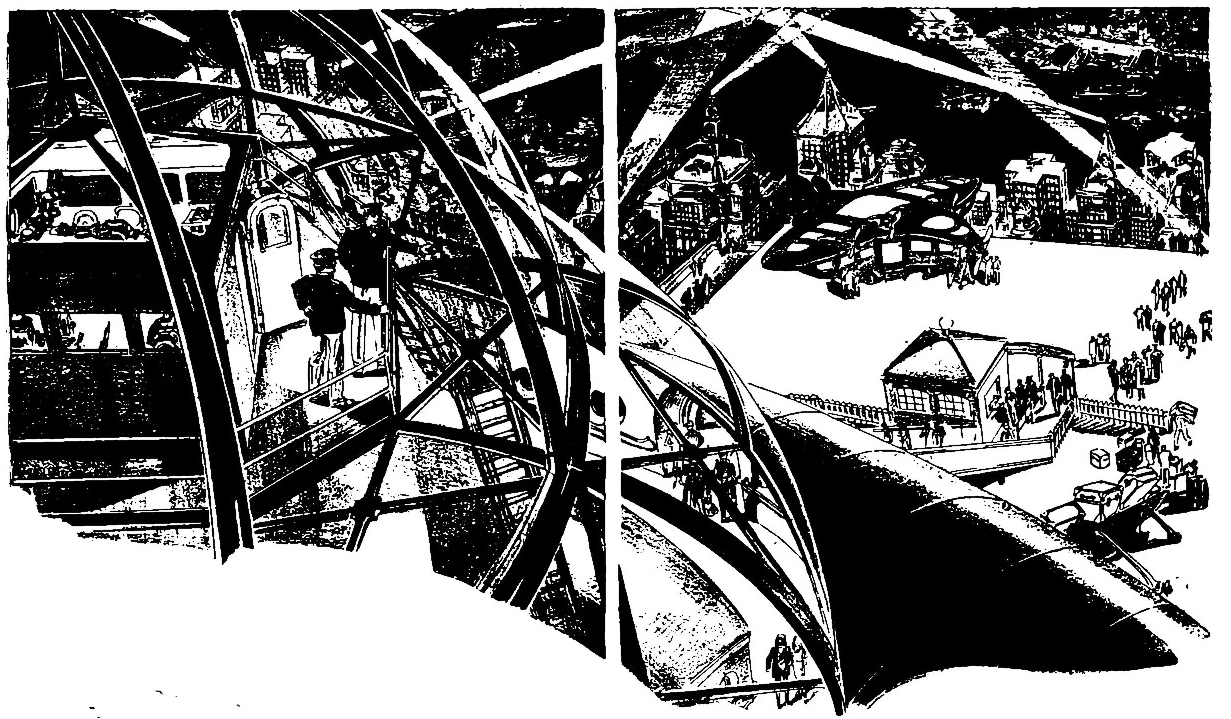

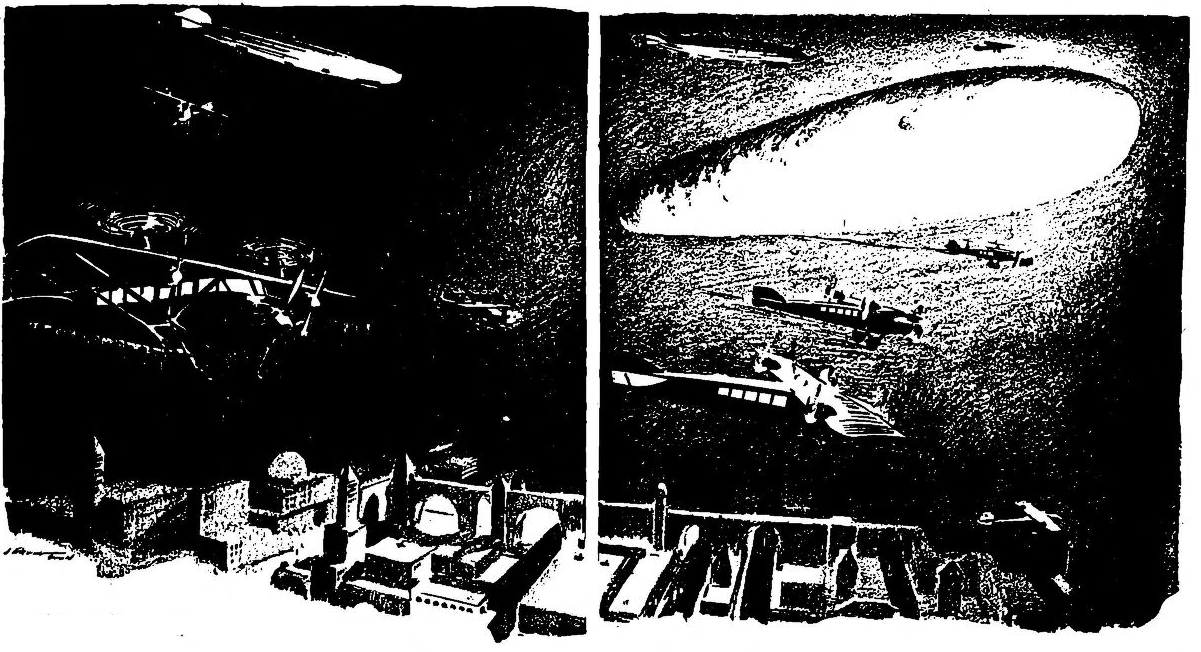

A vast flaming object, shaped like a Zeppelin but much larger in size, descends from the sky and hovers above Manhattan. The sight causes large-scale panic, and mass riots lead to martial law being declared around the world. The object then rises and vanishes, only to reappear in Chicago, this time close enough to the surface for its heat to kill thousands of people. Other cities report similar incidents, before the object returns to the skies of Manhattan.

A council of five men discuss the crisis. Together, they form a group of oligarchs who have controlled global affairs since 1975, ushering in an era of world peace: “A confederation of the countries of the world was brought about by industrial kings who had learned, in one devastating war, that militarism, while it might bring riches to a few, was, in the final analysis, destructive and wasteful.”

The five magnates offer different theories as to the object’s origin. Some speculate that it is a craft driven by life from another planet; but one of the five – Stanton, who has flown close enough to get a clear look at the object – insists that it is itself a form of life, a metal being with a metal brain.

Led by the bold Dirk Vanderpool, who controls the world’s transport industries, the oligarchs take a plane and land upon the vast body once it has sufficiently cooled. Finding an entrance, they soon encounter the craft’s crew: “piercing-eyed beings, who had all the characteristics of humans… clad in tight-fitting attire of thin and pliant metal”.

Orlando Fragoni, the most influential member of the council, meets the leader of the space-travellers, who turns out to speak English (“Life grows out of the substance of the universe and language comes out of life… I have heard your English, as you call it, spoken among those who dwell in many, many worlds”). He introduces himself as Teuxical, vassal of his Supreme Highness, Malfero of Lodore.

The earthmen are mostly persuaded that the Lodorians mean no harm and take them to visit the surface; Stanton, however, remains suspicious. Conflict breaks out when Teuxical’s insolent son Zitlan invites Inga, daughter of Orlando Fragoni, to join his harem, prompting Dirk to punch him on the jaw. Teuxical ends the argument by shooting both parties with a disabling ray.

When Dirk eventually regains consciousness, he learns that the situation has worsened. The other council members have found that the Lodorians’ emperor, Malfero, has the brutal practice of abducting inhabitants of other worlds and altering their minds to make them obedient slaves – and earth is lined up to be the empire’s latest tributary. The noble Teuxical insists that he will ensure a peaceful rule; but the council fears that it will be only a matter of time before the ruthless Zitlan takes the throne in his place. And so, Dirk declares that humanity’s only option is to completely wipe out the Lodorian visitors.

The heroes secretly weld a destructive device to the side of the Lodorian craft. Before it is due to activate, they learn that Zitlan has murdered his noble father – neatly eliminating the protagonists’ ethical concerns about having to do so themselves – and abducted Inga. The story ends with the heroes fighting off the Lodorians (along with Stanton, who has defected) and rescuing the girl, escaping just in time for the Lodorian craft to be destroyed by bolts of artificial lightning emanating from Orlando Fragoni’s palace, the device welded to the ship being a targeting mechanism. Aside from the ship killing a few thousand unfortunate bystanders as it crashes, peace is restored.

“Vandals of the Stars” is a case study in how the alien invasion genre had developed in the decades following H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. Already we see an emphasis on spectacle – particularly with the initial arrival of the alien ship and its eventual destruction – that would be a key element of the genre once it became a popular film subject in the fifties. We can also see how futuristic settings, with the surrounding technological advances that come with them, had become so common in science fiction that they could serve as background trappings, rather than integral aspects of the main premise.

In “Vandals of the Stars” the characters have a wide range of gadgets at their disposal. Aside from the artificial lightning that destroys the ship in the finale we are introduced to a “luciscope” (a combination of telescope and spotlight), a television-based communication device, “morphite gas” (used by the police to quash riots), helicopters (which have apparently replaced cars) and weapons that project something called a Z-ray, whatever that might be.

The future backdrop also allows author A. T. Locke to imagine a forthcoming form of government – with less than convincing results, it has to be said. The story explicitly states that, although the public are led to believe that they have democratic representatives, the world is ruled by a secret cabal of oligarchs. The rulers, side from the traitorous Stanton, are portrayed as being sufficently capable and benevolent to have achieved world peace so stable that only an alien invasion stands to threaten it. This recalls H. G. Wells’ ideal for government by an elite caste of scientists (described in A Modern Utopia and elsewhere) as filtered through an American faith in free-market capitalism.

As unconvincing as this part of the worldbuilding may be, the story’s weakest link is the uninspired portrayal of the alien invaders. The Lodorians are simply spacefaring Aztecs, bearing pseudo-Mesoamerican names and performing human sacrifice (Inga learns that the Lodorians have a rite in which they “tear out the hearts of living victims… and burn them on their high and mammoth pyramids.”) Here we see the common practice of building alien worlds out of stock character types from more earthbound adventure fiction – in this case adding distinctly unpleasant context to the scene in which the dashing Dirk, playing conquistador, demands the death of every last Lodorian visitor.

Despite a knack for spectacle, author A. T. Locke appears to have contributed only one further story to Astounding: “The Machine that Knew Too Much”, published in the December 1933 issue.