Main Cast: Billy Bob Thornton (Samson Young), Amber Heard (Nicola Six), Jim Sturgess (Keith Talent), Theo James (Guy Clinch), Jason Isaacs (Mark Asprey), Cara Delevingne (Kath Talent), Gemma Chan (Petronella), Jaimie Alexander (Hope Clinch), Johnny Depp (Chick Purchase – uncredited), Lily Cole (Trish Shirt)

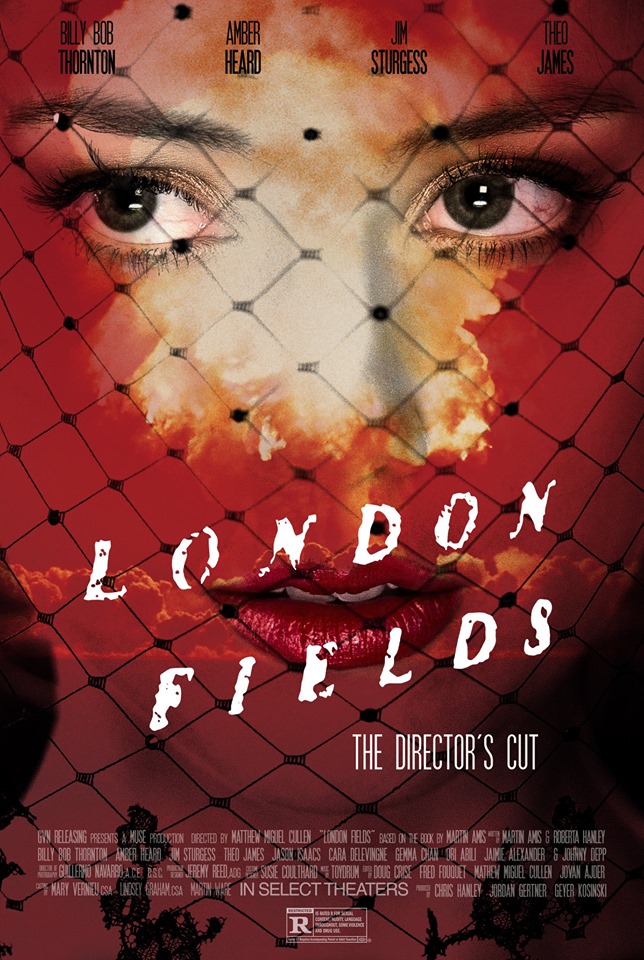

London Fields is a film adaptation of the 1989 novel of the same name by Martin Amis. It was shot, the début film of director Mathew Cullen, in 2013 and was intended to be released in 2015, but then fell subject to various complex legal disputes (these have been chronicled in depth at the Hollywood Reporter) resulting in at least one ‘producer’s cut’ of the film which eventually played in the US last November. Somewhat confusingly, there are reports on-line that other ‘producer’s cuts’ have played in other countries – the Internet Movie Database lists the film as having 38 producers of various stripes. All of which led to Cullen eventually spending his own money to prepare his director’s cut, and which played in a handful of theatres at the same time as the producer’s cut gained a wide release.

London Fields is a film adaptation of the 1989 novel of the same name by Martin Amis. It was shot, the début film of director Mathew Cullen, in 2013 and was intended to be released in 2015, but then fell subject to various complex legal disputes (these have been chronicled in depth at the Hollywood Reporter) resulting in at least one ‘producer’s cut’ of the film which eventually played in the US last November. Somewhat confusingly, there are reports on-line that other ‘producer’s cuts’ have played in other countries – the Internet Movie Database lists the film as having 38 producers of various stripes. All of which led to Cullen eventually spending his own money to prepare his director’s cut, and which played in a handful of theatres at the same time as the producer’s cut gained a wide release.

If you have heard of the film at all it is probably because it has gone down in box-office history, when adjusted for inflation, as the fifth lowest-grossing film ever to have a major release in the US. According to Box Office Mojo, London Fields grossed $252,676 from 613 theatres. The reviews were bad to terrible. All of which begs the question, why are you spending your time reading about it? Well, that would be because the director’s cut is a much more interesting piece of work than what those few who did go to the theatre saw last year. (There is an extensive list of the differences between the US theatrical version and the director’s cut on the Internet Movie Database, though obviously this list contains spoilers, including for the end of the film.)

But first to backtrack a little to say a something about the source material. London Fields, the book, is Amis’ sixth novel, and generally considered to be one of his best, coming in that period between Money (1984) and The Information (1995) when everything he wrote was both an instant bestseller – in the UK at least – and beloved of the literary critical mainstream. London Fields, it should be noted has science fictional underpinnings, (as does the novel Amis wrote immediately afterwards, Time’s Arrow), in that the novel is set ten years into the future from when it was published, in a London on the verge of societal collapse, environmental catastrophe and possible nuclear attack, and features a heroine who possibly has the ability to foresee the time of a person’s death, including her own. Amis is co-credited with the screenplay for London Fields – reportedly he wrote the first draft, which was then reworked by Roberta Hanley. Previously he had penned the screenplay for the 1980 science fiction thriller, Saturn 3.

The producer’s and the director’s versions of London Fields tell the same story, but there are very important differences. Cullen’s version is approximately 12 minutes longer than the theatrical cut, the pacing is slower, and due to the fact that much of the music is different, Cullen’s edition has a very different feel to the producer’s film (Cullen is an acclaimed director of music videos), while the director’s incorporation of stock footage evoking the history of the nuclear age gives his version a much wider context, placing the tale in a city hovering on the very edge of Armageddon – one of the first things we learn is that two nuclear warheads are pointing at London from an orbital platform, and that everyone with the means to do so is getting out of the city. The way Cullen’s cut is assembled is more cerebral, makes the audience work harder to follow the story. It is also less sensational – anyone looking for the soft porn raunchiness promised by the trailer for the theatrical version, which tries to sell the film as a sleazy neo noir erotic thriller, is likely to be disappointed.

London Fields, in whatever version, is about a down on his luck American writer, Samson Young (Billy Bob Thornton) who has done an apartment swap for a few months with a far more successful British author. The decaying London apartment he finds himself in is far from desirable. However, the ageing Young is looking for inspiration for a new book which will revive his flagging career, and his London apartment building does have one plus point – it is home to Nicola Six (Amber Heard), who agrees to allow Young to write her story after he discovers that she knows both when she will die and that one of three particular men will be her murderer. So much, so high concept.

The film has a starry cast, with roles for Cara Delevingne, Jason Isaacs, Theo James, Jim Sturgess, Lily Cole and an uncredited Johnny Depp, has top notch production values and is gorgeously shot by Guillermo Navarro (Pan’s Labyrinth, From Dusk Till Dawn, Twilight: Breaking Dawn, Pacific Rim). The score by Toydrum (Adam Barber & Benson Taylor), with additional music by Andrew Pearce, spans elegant Herrmannesque menace and ethereal wonderment to highly atmospheric affect. The screenplay retains key lines and dialogue from the novel, and while a film is not a book – what would be the point in essentially a multi-million-dollar photocopy job? – Cullen strives to find fitting cinematic devices to match the spirit of the text.

London Fields, the novel, is a highly stylised piece of work, on one level a metafiction about the process of writing a novel, on another a book about how people manipulate and control one another through the stories they tell and the images they present to the world. Amis’ trick is to embody sufficient fresh life into stereotypes – the has-been grizzled old hard-drinking writer, the man-eating femme fatale, that the reader willingly goes along with the manipulations, those by Amis’s himself as well as those perpetrated by his characters. He makes the fabrications so entertaining that even if we don’t particularly care about the characters, we become invested in the outcome of their story. The film ups this anti with a whole other level of artifice, in that now we have not just two writers with their word-processors (one real, one imaginary), but a whole team of film-makers bringing the characters to life, and then rival teams of editors crafting different versions of the material in the hope that audiences will want to see their cut of the story.

And I should note, we have been here many times before. No one makes them do it, but for some reason film producers regularly decide to finance films based on complex, intellectually provocative material, then seem surprised when someone takes their money and makes a complex, intellectually provocative film with it, and so they try and turn that film into something it isn’t and can’t be, pleasing no one. Not all books appeal to the same readers, but somehow film producers so often take niche material and convince themselves that it can somehow be transformed into a film with wide, popular box office appeal. They are always wrong, and they never learn. Instead, rather than releasing a film of high quality which will appeal to a small audience, get good reviews and make some money, they panic and release a butchered, compromised version of the material which satisfies no one. And so it goes on, year after year, because too many film producers only seem to understand investment and deals and consider film just another product to sell, not an art to nurture, which if done successfully just might make them some money.

But back to the film itself. Little needs to be said about Billy Bob Thornton, because he is, of course, marvellous. A subtle, understated performance as a man living on borrowed time, trying to find some sort of redemption through creating a work which might actually mean something, or at least connect with an audience. Johnny Depp is excellent as the darts player and loan shark Chick Purchase, and while he isn’t in the film a great deal, he shines in every scene in which he is featured.

There are two other key performances which are much more controversial and require more discussion. Jim Sturgess plays Keith Talent, a low life gambler and darts player who acts as a sort of fixer, kicking the plot along, getting things done, and he plays the part with such crazed energy, such gonzo vulgarity, enthusiasm and lack of inhibition, is so deranged and comically OTT, that he might well be in a different film to everyone else. It’s a love it or hate it performance that at first jars with the more sombre, serious tone of much of the film, but eventually comes to make sense and work in its own bizarre way.

Finally, there was much critical derision poured on Amber Heard for her performance, including a nomination for a Razzie Award as worst actress of the year. This seems largely due to the way the theatrical release version of the film was edited, but also misses the point that Heard had the very difficult job of playing a character who, even in the scenes in which she is ‘objectively real’ is essentially a caricature – knowing she is going to die soon, minutes after midnight on her rapidly approaching birthday, which is also the night of an eclipse and Guy Fawkes’ Night, Nicola Six has given up on conventional life and fashioned herself as a femme fatale, entertaining herself by adopting various erotic personas with the different men in her life. Yet who in many more scenes she isn’t even really a person at all, but is a fantasy of Samson Young’s imagination as he attempts to transmute what he sees of her life into some sort of significant fiction. In fact, throughout the film there is an ambiguity over how much of what we see is ‘real’, and how much stems from Young’s mind. Given all this, Heard does a fine job of playing, not a real woman, but a literal embodiment of male fantasy – hence her often downcast or closed eyes or far away glances into which any desire might be read.

None the metafictional games the film plays are original, thought it must all have seemed fresher 30 years ago when the novel was first published – and it must be said that the novel is much funnier than the film. But even then it was over a decade on from Alain Resnais’ brilliant 1977 film Providence, in which a dying writer (John Gielgud) based his final novel on his distorted perceptions of his family – and that film had an incredible cast including Dirk Bogarde, Ellen Burstyn, David Warner, Elaine Stritch, Denis Lawson and Kathryn Leigh Scott. Since then we’ve had metafictions a plenty, and if none of it actually adds up to anything truly profound, then Cullen puts it together with great verve and style with the result that the film is tremendously engrossing and enjoyable.

The approach of Guy Fawkes’ Night means London is awash with fireworks and flame, adding to the sense of impending apocalypse, though this aspect of the story may well be lost on international audiences unaware of how the British go a little mad in the autumn, igniting fireworks seemingly at random and burning bonfires in celebration/commemoration (no one is quite sure which) of the man who failed to blow up Parliament at the beginning of the 17th century. The film would make a wonderful double-feature with the 2016 British film High-Rise, wherein the collapse of society is enacted in microcosm in a single tower block. Like London Fields, High-Rise was also based on a decades-old novel by one of Britain’s literary elite – though JG Ballard has stronger groundings in the science fiction world.

Another aspect of London Fields which may have passed American critics by, is how brilliantly Cullen finds metaphors for Amis’ metafictional tale by ironically evoking images from the glorious Technicolor past of British cinema. British cinema is often unfairly defined either by its kitchen sink realism or its heritage industry costume dramas. But there is another side to British cinema, that of the fantastic flights of fantasy embodied in the work of such geniuses as Powell & Pressburger, Ken Russell, Nic Roeg, John Boorman, as well as Anglophile Americans such as Stanley Kubrick and Terry Gilliam (who both made much of their best work in Britain).

Thus in London Fields you may spot homages equally to the visual poetry of Powell & Pressburger – some scenes, particularly those in which Nicola Six romances the upper class Guy Clinch (Theo James) are so beautifully and elegantly shot they might come from a 1950s British CinemaScope melodrama – and the extreme shock tactics of Ken Russell (one sequence is essentially a reworking of the bit with the nightstick from Russell’s Crimes of Passion that got cut from the US R-rated version of that film but happily graced the silver screens of the UK.)

Cullen also plays with time and montage in a way which invokes Nic Roeg, for time is out of joint here just as it is in Don’t Look Now, a great British film in which a premonition of death is famously misinterpreted. There is even a shot of Theo James, who often seems to be channelling a young Roger Moore, sitting at the wheel of his car which may or may not be a deliberate call back to the wonderful British exploration of fractured identity, The Man Who Haunted Himself. Guy Clinch is certainly haunted by Nicola Six and would be a shoo in for the role of Simon Templar in any new version of The Saint.

Last but not least, there is the Kubrickianness of the piece. Jim Sturgess’ Keith Talent comes across like a droog from A Clockwork Orange, but one who has grown up and settled down to an unsatisfactory married life on an inner London council estate while occasionally competing as a professional darts player. His nemesis, bowler hat wearing Chick Purchase, proves himself up for a bit of the old ultra-violence. This entire aspect of the story, from costumes to locations mainlines a pure Clockwork Orange vibe. That is perhaps, apart from one decidedly unerotic daylight sex scene, which plays like a moment from a very different sort of British cinema – Rita, Sue and Bob Too.

Which, given the way London Fields has been sold, inevitably brings me to the sex. The two sex scenes I’ve referred to already are not remotely titillating, while the other two sexual encounters in the film are, by contemporary standards, extremely discreet in their presentation. While there is a lot of sensuality – the camera adores the astonishingly beautiful Amber Heard – there is almost no nudity, and very little that is really graphic. Even the nod to Crimes of Passion is much tamer visually than the original. Nevertheless Nicola Six remains a fantasy figure who to all intents and purposes is only valued for her physical beauty and sexuality in relation to the men in the film, and who is doomed to die at the hands of one of them – though appropriately for a film about fantasy almost everything is left to the imagination. Ultimately London Fields lives or dies in the eye of the beholder.

As for the science fictional elements of the story, in the end they amount to something of a MacGuffin, as while the city forever hovers of the edge of destruction, the apocalypse which finally visits the central characters is purely personal. Other than an inciting device, nothing is developed from Nicola Six’s supposed prophetic powers. This is not that kind of story. I can do no better than to quote the opening lines of the novel, which find themselves reworked in the film:

This is a true story but I can’t believe it it’s really happening.

It’s a murder story too. I can’t believe my luck.

And a love story

Whatever its merits, and as a piece of filmmaking they are considerable, London Fields will divide opinion. It will certainly find more favour among serious film fans in this director’s cut. Mainstream audiences are likely to remain confused, or simply uninterested. London Fields isn’t perfect, but it is hugely ambitious and shows great talent (no pun intended). It could be the beginning of something remarkable – it’s obviously far too early to tell, but perhaps one day we might consider Mathew Cullen a worthy successor to Roeg, Scott, Kubrick – that is if the notoriety surrounding the film and its commercial failure does not kill his career as prematurely as London Field’s tragic heroine meets her untimely demise.

*

With thanks to Nick Clement for the opportunity to see the director’s cut of London Fields

…is a freelance editor, writing consultant and story structure expert. To find out more, including hiring me to work on your writing project, read my profile or visit my website, To The Last Word.

Recent Comments