I always said I wouldn’t write reviews here–that’s not the purpose of this blog–but a glowing recommendation seems like it fits right in.

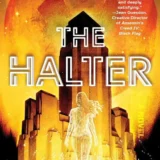

I was a huge fan of The Divine Cities trilogy, so I was really looking forward to Foundryside by Robert Jackson Bennett (August 2018, Crown), and it did not disappoint. Foundryside  is the first book in a The Founders Trilogy and does what a first book is supposed to do–define the world and its rules, tell a self-contained story, while setting up the next book in the trilogy and the larger battle to come.

is the first book in a The Founders Trilogy and does what a first book is supposed to do–define the world and its rules, tell a self-contained story, while setting up the next book in the trilogy and the larger battle to come.

The Divine Cities books were all quite political, but if I had to pick, I’d say their focus was religion and its interaction with societies and politics more than politics itself. Foundryside is about economics and politics, which might make it sound dry, but instead it’s anything but, layered and fascinating, with a heist plot driving the action along.

The main character, Sancia, is a thief with a “scribed” plate in her head that lets her understand inanimate objects in a way that is painfully intimate. She lives in Tevanne, a capitalist society taken to its logical endpoint where the haves have everything, and the have-nots next to nothing. Like all good heist stories, this one begins when Sancia steals something far more valuable than she bargained for, a key that can unlock any door, and has a bit of a personality of its own.

This book is populated with fascinating characters, each with their own motivations and backstories, which sometimes converge and sometimes conflict. Morality is a bit out of fashion in this world of pure commerce.

An aspect I was concerned about when I started reading was how claustrophobic the world felt–we are in one city with commercial ties to the rest of the world, but little interest in them. But that claustrophobia is very important to what Bennett seems to be trying to do in this novel. A society based entirely on commerce is small and stifling, no matter how cosmopolitan it seems. Viewing every relationship as transactional diminishes all relationships, and when justice is for sale, it is not justice at all.

Sancia gained her skill with objects because of a horrific experiment that was performed upon her, and gives her what the reviewer at Tor.com called a chronic illness–and it’s a metaphor that makes sense. Sancia is saving up for an operation that might make her “normal” again, and whenever she uses her skill it takes a toll on her, using up her spoons. It is vital to the functioning of the book’s plot, so much so that I ended up wanting Sancia relieved of her pain, but wishing it didn’t have to come at the cost of her remarkable abilities.

The magic system in Foundryside is very well imagined too, a sort of magical computer programming, where the words of the programming language control the mechanisms of the universe. Sometimes books that get too into the rules of the magic can be tiresome, but even though the magic in this book is both literally and metaphorically cumbersome, it plays into the theme that Bennett is developing here. You could see Tevanne as a Silicon Valley gone even more too far than ours. Slavery is an aspect of this world that is mostly kept off-screen, and that too works with the Silicon Valley metaphor.

Even with the density of heavy themes and weighty magic, this book has a wry, dark humor to it. Every character is capable of looking foolish from time to time. And the heist-driven plot keeps everything exciting. I can’t wait to read the next book in the series: Heirophant, likely out next summer.

Read Linnea’s profile