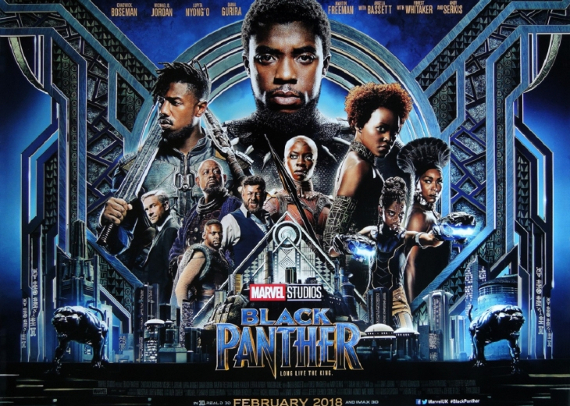

Rating: 8 out of 10

Cast:

Chadwick Boseman as T’Challa / Black Panther

Michael B. Jordan as N’Jadaka / Erik “Killmonger” Stevens

Lupita Nyong’o as Nakia

Danai Gurira as Okoye

Martin Freeman as Everett K. Ross

Daniel Kaluuya as W’Kabi

Letitia Wright as Shuri

Winston Duke as M’Baku

Angela Bassett as Ramonda

Forest Whitaker as Zuri

Andy Serkis as Ulysses Klaue

Directed by Ryan Coogler

By equal turns specifically relevant and universally relatable Black Panther – the newest entrant in the Marvel Cinematic Universe – is as good anything the studio has ever produced (and better than most) boosted by fantastic visuals and one of the best villains in the superhero film lexicon in the form of Michael B. Jordan’s Erik Killmonger.

Picking up a week or so after the end of Captain America: Civil War (and thus relatively simultaneous to Spider-Man: Homecoming and likely a year or so prior to the upcoming Avengers: Infinity War) Black Panther follows the formal ascension of crown prince T’Challa (Boseman) to the throne of Wakanda after the death of his father. Though he’s been training for his entire life to become the Black Panther, the protector of Wakanda and the potentially world-changing technology it has developed from the fantastic space metal vibranium it controls, nothing could prepare him for the nature of actually being king which means both dealing with the sins of his country’s (and the world’s) past and his responsibility to its future.

Black Panther as a character has always been an enigma, which is a nice way of saying most of his writer’s haven’t had a good idea about what makes him tick and have not bothered coming up with an answer. With a few very celebrated examples he has been more reactive than active, a hero who deals with plot elements because that is his role but not much more. Even Christopher Priests’ much-admired early 2000s run on the character took the short-cut of introducing liaison officer Everett Ross (here played by Sherlock’s Martin Freeman) to handle things like dialogue and plot elocution because T’Challa internalized EVERYTHING.

Co-writer/director Ryan Coogler’s (Creed) take on the character doesn’t quite have that problem (mainly because it can’t, this is a movie after all) but it does spend quite a bit of time struggling to figure out who he is and what he should be doing, leaving him reacting to the world around him now that he has more than a simple revenge quest to focus on. But at least this version of T’Challa talks about this struggle, reveals how much he is specifically aware of it and how much it is troubling him which creates depth the character has traditionally lacked. It’s not a space he can remain in forever, there is a supreme difference between raising a question and answering it and it becomes very clear when there is no answer, but for now it’s good enough.

And that’s because for all intents and purposes T’Challa is not the main character of Black Panther (he’s certainly not where its heart is); Michael B. Jordan’s Erik Killmonger is.

The problem with superhero films, which most fantasy can avoid, is that it is set in the present day in order to enhance the personal fantasy that ‘this could happen to me.’ But this means ultimately coming with rationalizations about how real world status quo remains in place while people like Superman or Mr. Fantastic are running around. They exist in the real world but ignore. The Marvel films have not entirely done that – they are still dealing with the after effects of the alien invasion in the first Avengers film, not to mention the fallout from Avengers 2 several years later – but many of the problems it deals with are of the superhero making, leaving societal issues on a backburner. Black Panther wants to do away with that paradigm. It seeks out to face these issues head-on, dealing with the long-term consequences of colonialism and the African slave-trade and how it is has impacted the world of today, specifically the United States.

Killmonger is a walking, talking indictment of the modern African-American experience. Raised in the slums of Los Angeles he’s lived his life as a man forced to the margins because of his race and he is determined to do something about it. Seeing in Wakanda and its technology the power to do something about this not just for the country he grew up in but for his brothers all around the world, Killmonger is determined and willing to do whatever it takes to make things right. It’s a message which resonates not just for the audience but for the people around Killmonger, forcing them to ask ‘why have we allowed this to go on for so long?’

It’s a fantastic role, one which could have been merely a proxy for a societal point of view but which is clearly and sharply characterized both by Jordan’s performance (charismatic without ever being over-the-top — that job is left to Andy Serkis’ Ulysses Klaue) and Coogler’s decision to tie his needs so sharply to Killmonger’s specific past, the loss of his father and what that meant to him. It also makes Killmonger not so much an opposite as a brother (or sorts) to T’Challa, so close in history and mindset that it’s easy to see the hero going down a similar path if things had turned out differently. More importantly nothing Killmonger wants is specifically for himself, his larger goals have more to do than mere power, and it’s not entirely clear his opponents are in the right even if his methods are too extreme.

Not that Black Panther isn’t also an impeccably crafted bit of pulp entertainment. Panther’s armor and various gadgets, plus Wakanda’s mixture of high-tech and tribal culture, offer up a smorgasbord of options for set pieces and Coogler plays them for all their worth. An early visit to a Korean gambling den (and ensuing car chase) plays like a giant, fantastic Bond sequence and the third act finale takes advantage of the multi-sequence cross-cut adventure style George Lucas once honed in his Star Wars films as the various tribes of Wakanda fight each other over the country’s future while T’Challa and Killmonger fight it out on top of an underground train.

Panther’s supporting cast is also excellent, particularly the triumvirate of Lupita N’yongo, Danai Gurira and Letitia Wright as his ex-girlfriend, captain of his personal guard and genius sister who push and prod him to action even as they try to figure out where they exist in relation to him. Besides being excellent in their own right (Wright in particular is a scene stealer) they also give Coogler and Boseman some breathing room on what to do with T’Challa (who actually vanishes from his own film for nearly an entire act). The design of the film, especially Wakanda itself, is also strong – imagining a fully developed African nation which never dealt with colonization – creating a fully believable world while also filled with the artisan touches that tell fantasy apart from reality.

While none of this completely deals with the long term problem of Black Panther himself it does provide a potential new archetype for how superhero films can be and particularly how they can react to and reflect the real world. At some point, and by some point I mean the next film, Marvel and its filmmakers are going to need to come up with more of a raison d’être than just protecting Wakanda or he’ll never reach the potential Coogler and company have set up for him. But that’s a worry for the future; for now Black Panther is as good a superhero film as has been made and is worth reveling in.