Abraham Merritt (1884-1943) was once amongst the most popular fantasy and horror writers in the English language. During his lifetime, his works topped readers’ polls held by the magazines Argosy and Wonder Stories, and he maintained enough posthumous name recognition for a publication entitled A. Merritt’s Fantasy Magazine to launch six years after he died.

Abraham Merritt (1884-1943) was once amongst the most popular fantasy and horror writers in the English language. During his lifetime, his works topped readers’ polls held by the magazines Argosy and Wonder Stories, and he maintained enough posthumous name recognition for a publication entitled A. Merritt’s Fantasy Magazine to launch six years after he died.

And yet, today, A. Merritt has long since drifted from the public imagination.

One possible reason for this is the lack of films based on his stories. Edgar Rice Burroughs, Johnston McCulley and Dennis Wheatley are no longer the household names they once were, but their characters — Tarzan, Zorro, Mocata — live on in celluloid. A. Merritt, on the other hand, had only two of his novels adapted for the screen: Seven Footprints to Satan (1927) and Burn, Witch, Burn! (1932). In neither case did the films leave a discernible mark on horror cinema.

Perhaps it is time to take a closer look at how the works of this great fantasist fared in the world of motion pictures, and shine a light on a long-forgotten intersection between literary and cinematic horror fiction……

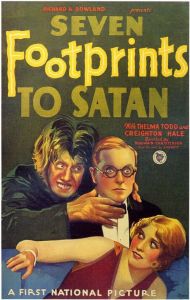

Seven Footprints to Satan was originally serialised in Argosy in 1927 before being collected as a novel in 1928, and later printed by Argosy once more in 1939. The film version, meanwhile, was a late-period silent movie directed by Benjamin Christensen for First National Pictures and released in 1929. A sound version came out the same year, but only the silent film survives.

Seven Footprints to Satan was originally serialised in Argosy in 1927 before being collected as a novel in 1928, and later printed by Argosy once more in 1939. The film version, meanwhile, was a late-period silent movie directed by Benjamin Christensen for First National Pictures and released in 1929. A sound version came out the same year, but only the silent film survives.

The main character in Merritt’s story is explorer James Kirkham; when he is not globe-trotting, Kirkham spends his time at the Discoverers’ Club in New York. But one night he is kidnapped and taken to the mansion of an individual who purports to be Satan himself; here, he must endure a series of trials as Satan’s captive.

In the film, James Kirkham is played by Creighton Hale. This actor had previously played a comedic character in Universal’s haunted house mystery The Cat and the Canary (1927), and his knock-kneed portrayal of Kirkham is essentially a reprisal of his earlier role. This is a significant departure from Merritt’s story: unlike the experienced traveller of the novel, the film’s James Kirkham is a naïve young man who merely dreams of becoming an explorer. His introductory scene in the movie has Kirkham locked in a room with a selection of firearms, using lit candles as target practice in preparation for a voyage to darkest Africa; this eccentric behaviour is contrasted with the straight-talking nature of his Uncle Joe, a character invented for the film.

The film depicts the abduction of Kirkham as a simple matter of him being ushered into a car and driven off to Satan’s mansion, but in the novel the scheme is rather more elaborate. The kidnappers cart Kirkham through New York, persuading any curious observers that he is a mentally ill man who merely believes that he is the noted explorer Kirkham; they even hire an imposter to take his place at the club. There is nothing particularly humorous about this sequence, yet it is the closest thing in the novel to the film’s portrayal of Kirkham as comically addle-headed.

In the book, Satan’s mansion is marked by its opulence: “It was as though the choicest treasures of medieval France had been skimmed of their best and that best concentrated here.” While captive, Kirkham is presented with champagne made for the exclusive use of King Alfonso of Spain, poured into a rock crystal goblet that once belonged to Caliph Haroun-al-Raschid. Nearby on the table is a compote made by Benvenuto Cellini.

The butler who serves upon Satan and his prisoner, meanwhile, turns out to be a Chinese prince of the Manchu dynasty. Satan shows a fondness for servants hailing from exotic climes, whose descriptions descend further into grotesque racial caricature as the story unfolds. Kirkham later encounters seven men in Arabian dress, with gaunt skin and pupilless eyes. After that appears “a figure that the devil himself might have summoned from hell… a black man naked except for a loin cloth”, with an “ape-like” jaw and eyes and “the stamp of a ravening cruelty” upon his face. This man is Satan’s executioner, and bears a noose “thin and long and braided as though made of woman’s hair”.

The butler who serves upon Satan and his prisoner, meanwhile, turns out to be a Chinese prince of the Manchu dynasty. Satan shows a fondness for servants hailing from exotic climes, whose descriptions descend further into grotesque racial caricature as the story unfolds. Kirkham later encounters seven men in Arabian dress, with gaunt skin and pupilless eyes. After that appears “a figure that the devil himself might have summoned from hell… a black man naked except for a loin cloth”, with an “ape-like” jaw and eyes and “the stamp of a ravening cruelty” upon his face. This man is Satan’s executioner, and bears a noose “thin and long and braided as though made of woman’s hair”.

It is later established by Barker, a Cockney burglar whom Kirkham befriends, that Satan plies these servants with a drug called kehjt. “You’ve ‘eard of the Old Man of the Mountains who used to send out the assassins”, says Barker. “Satan’s gyme’s the syme.” The drugs, it turns out, are hallucinogens that produce the illusion of the paradise desired by each user.

Some of these servants make it into the film – most notably, Japanese actor Sōjin Kamiyama plays a character presumably based on the Chinese butler – but on the whole, the adaptation is concerned less with exoticism and more with deformity and disfigurement. The denizens of Satan’s mansion seen onscreen include a dwarf, a man with an excessively hairy face, a “Beast of Satan” portrayed by an actor in an ape suit, and a sinister-looking fellow dubbed the Spider, who walks on a pair of crutches. In the novel, Satan’s servants are prone to disappearing into lifts hidden behind wall panels; the film latches onto this concept, with various strange characters popping in and out of the walls to confuse and bewilder Kirkham. This is another similarity to The Cat and the Canary, which likewise made use of a mansion containing hidden passages.

Another major difference between the novel and the film is how they approach the main villain. In the book, Kirkham describes Satan as being “the exact opposite of the long, lank, dark Mephisto of opera, play and story.” He is an imposing figure, seven feet tall and broad-chested. His blue eyes are gem-like in their depth and hardness, lashless and unblinking. His large, bald head has a capacity “almost double that of the average”. He has a statuesque quality, with skin that resembles marble in its smoothness and colour.

“I am a connoisseur of men and women”, he says. “A collection of what, loosely, are called souls. That is why, James Kirkham, you are here!” When Kirkham brings up the legendary contract of blood, Satan dismisses this out of hand. “Obsolete methods… I gave them up after my experiences with the late Dr. Faustus”, he says. “I have become more modern. I still buy souls, it is true. Or take them. But I am not so rigorous in my terms as of old. I now also lease souls for certain periods. I pay well for such leases, James Kirkham.”

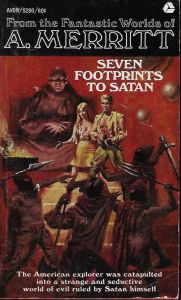

Is this character truly Satan? This matter is initially left ambiguous. The burglar Barker is the first to argue that that the owner of the mansion cannot be Satan, as Satan is confined to Hell (“An’ won’t ‘e just give this bloody swine particular ‘ell for tykin’ ‘is nyme in vyne when ‘e gets ‘im in ‘ell!”) But even if this Satan is not a genuine demon, he comes across as something more than human. In the novel, Merritt creates a quasi-supernatural crime lord in the tradition of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu. He even plays with the same strand of “yellow peril” imagery: Barker concludes that “Satan” is a mixed-race man of Russian and Chinese ancestry, and the villain’s apparent Chinese connections are brought up later on in the novel, even though his exact history is left a mystery. It is possible that Merritt was drawing upon Chinese Buddhist iconography in describing his bald-headed antagonist; certainly, the cover of the 1968 Avon paperback shows a distinctly Buddha-like interpretation of the story’s villain.

Is this character truly Satan? This matter is initially left ambiguous. The burglar Barker is the first to argue that that the owner of the mansion cannot be Satan, as Satan is confined to Hell (“An’ won’t ‘e just give this bloody swine particular ‘ell for tykin’ ‘is nyme in vyne when ‘e gets ‘im in ‘ell!”) But even if this Satan is not a genuine demon, he comes across as something more than human. In the novel, Merritt creates a quasi-supernatural crime lord in the tradition of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu. He even plays with the same strand of “yellow peril” imagery: Barker concludes that “Satan” is a mixed-race man of Russian and Chinese ancestry, and the villain’s apparent Chinese connections are brought up later on in the novel, even though his exact history is left a mystery. It is possible that Merritt was drawing upon Chinese Buddhist iconography in describing his bald-headed antagonist; certainly, the cover of the 1968 Avon paperback shows a distinctly Buddha-like interpretation of the story’s villain.

Almost all of this is lost in the film version. Here, Satan appears only in the climax, and is portrayed as a nondescript-looking man wearing a black sheet over his head. For the rest of the film it is Satan’s various servants and associates who act as his representatives; indeed, the film’s publicity materials played up the devilish-looking Spider (a character not found in the novel) as the main villain.

Another character who was drastically changed in the adaptation is Eve Demerest, the heroine. In the novel she is an ambiguous figure, introduced as one of the people aiding Kirkham’s kidnapping but later revealed to be merely another poor soul forced into Satan’s servitude. Satan later reveals that his ultimate plan is to rape Eve and impregnate her with a son, who will grow to become his heir (Satan has had children previously, he explains, but “They were girl children… They were disappointments. Therefore, they ceased to be.”). Kirkham takes it upon himself to rescue her, and despite their initial adversity, the two become allies – and lovers.

In the film, meanwhile, Kirkham and Eve (played by Thelma Todd) know each other from the start, and are kidnapped together. Eve’s main role is to act as a straight partner to the fearful Kirkham, before becoming a damsel in distress for the climax. The film also introduces another character, a black-haired woman, who appears to be based around the more ambiguous aspects of Merritt’s Eve: at times she appears to be helping the protagonists, at others she serves Satan.

In the film, meanwhile, Kirkham and Eve (played by Thelma Todd) know each other from the start, and are kidnapped together. Eve’s main role is to act as a straight partner to the fearful Kirkham, before becoming a damsel in distress for the climax. The film also introduces another character, a black-haired woman, who appears to be based around the more ambiguous aspects of Merritt’s Eve: at times she appears to be helping the protagonists, at others she serves Satan.

The title itself refers to a game of chance that Satan plays with his victims. Inspired by the legendary footsteps of Buddha, he has placed seven footprints upon a set of stairs leading to a throne. Four are lucky, three unlucky, but all are identical.

The player must choose four steps to tread upon. If they tread on all four lucky footsteps, then Satan must be their servant. But a player who treads on any of the unlucky footsteps will be forced to perform favours for Satan; how many favours depends on how many footsteps. If they stood on all three unlucky prints, then their mind, body and soul will belong to Satan, to kill or to keep as a slave as he wishes.

In the novel, Kirkham is not the only character to play this game. The first, Cartwright, nearly wins; but he then makes the fatal mistake of – like Lot’s wife – looking behind him, whereupon he sees the globe that records his choices. As punishment for this violation of the rules, he is forced to replay the game. This time treads on all three unlucky steps, and so becomes Satan’s latest victim.

In the film, only Kirkham plays the game. In both versions of the story he fails to tread on all four lucky steps, although he also avoids the worst fate, and so is sentenced to a period of servitude to Satan.

In the film, only Kirkham plays the game. In both versions of the story he fails to tread on all four lucky steps, although he also avoids the worst fate, and so is sentenced to a period of servitude to Satan.

It is at this point that the novel and film diverge to the most extreme degree. In the book, Kirkham is forced by Satan to help steal priceless objects for his art collection. All the while, Kirkham, Eve and Barker conspire to overthrow Satan. They eventually expose him as a fraud by revealing that his game of the seven footprints is rigged; his mystique is lost forever, and the self-proclaimed Satan faces a revolt amongst his own servants, who now realise that he is a mere mortal after all. This part of the story takes up the entire second half of the book.

The film ends things in a completely different manner. After Kirkham walks the steps and receives his three-year sentence of servitude, he learns the truth: “Satan” is actually his Uncle Joe, and the entire ordeal was no more than an elaborate prank! Everyone apparently killed or tortured by Satan’s minions turns out to be alive and well, having been in on the gag the whole time, and Kirkham’s three years of servitude are no more than three years as Joe’s employee. Kirkham had yearned for an adventure, after all, so Uncle Joe decided to give him one.

For context, the Hollywood of the silent era was wary of portraying supernatural horror head-on. The apparent hauntings in The Cat and the Canary turn out to the result of trickery, as does the vampire in London After Midnight (1927). Back in his native Scandinavia, director Benjamin Christensen was able to portray all manner of witchcraft and devilry in his 1922 film Häxan, but the American industry favoured the rationalised supernatural.

For context, the Hollywood of the silent era was wary of portraying supernatural horror head-on. The apparent hauntings in The Cat and the Canary turn out to the result of trickery, as does the vampire in London After Midnight (1927). Back in his native Scandinavia, director Benjamin Christensen was able to portray all manner of witchcraft and devilry in his 1922 film Häxan, but the American industry favoured the rationalised supernatural.

It should not come as too much of a surprise, then, that Seven Footprints to Satan ends by removing all ambiguity about the nature of its phony Devil. But not content with merely unmasking Satan as a mortal man, the film takes things a step further by rendering him completely innocuous. While Merritt’s Satan was not a true demon, he was still an intimidating and deadly villain; the same can hardly be said of the well-meaning Uncle Joe.

Between Hale’s comedic performance and the outrageous punchline to the story, the film ends up being less an adaptation of Merritt’s book and more of a parody of it. But then, adapting the novel was clearly not high on the agenda: the main aim of First National’s Seven Footprints to Satan seems to have been to mimic Universal’s The Cat and the Canary. In addition to the similarities mentioned above, the film of Seven Footprints seems designed to work as a loose sequel to the earlier film. The Cat and the Canary has Creighton Hale’s character involved in a squabble over inheritance money; Seven Footprints starts with Hale’s character having already inherited vast wealth.

Between Hale’s comedic performance and the outrageous punchline to the story, the film ends up being less an adaptation of Merritt’s book and more of a parody of it. But then, adapting the novel was clearly not high on the agenda: the main aim of First National’s Seven Footprints to Satan seems to have been to mimic Universal’s The Cat and the Canary. In addition to the similarities mentioned above, the film of Seven Footprints seems designed to work as a loose sequel to the earlier film. The Cat and the Canary has Creighton Hale’s character involved in a squabble over inheritance money; Seven Footprints starts with Hale’s character having already inherited vast wealth.

Taken as a spiritual successor to The Cat and the Canary, Seven Footprints to Satan is not too bad. It captures the general spirit of Universal’s film while also including enough new ingredients (carried over from the novel) to avoid being a mere rehash. That said, it is a shame that First National missed the chance to give filmgoers a full-blooded A. Merritt adaptation.

The following post in this series will look at how Merritt’s later novel Burn, Witch, Burn! fared on screen…