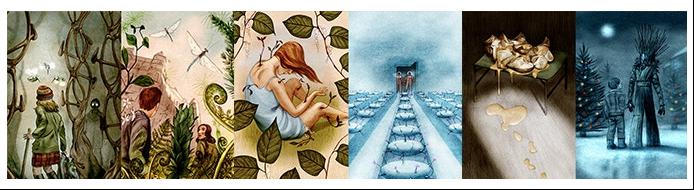

I have recently edited a new anthology of science fiction and fantasy stories about fantastical flora. The book, Improbable Botany, features authors who between them have won the Arthur C Clarke, British Science Fiction Association, John W. Campbell Memorial, Philip K. Dick, Nebula and Prometheus Awards, and been nominated for many more. The writers are: Cherith Baldry (co-author of the New York Times best-selling Warrior Cats series), Eric Brown (The Kings of Eternity, the Langham and Dupré crime novels, the most recent of which is Murder Take Three), James Kennedy (The Order of Odd-Fish), Ken MacLeod (Intrusion, The Corporation Wars), Simon Morden (the Metrozone series, Down Station / The White City), Adam Roberts (The Real-Town Murders, The Thing Itself), James Kennedy (The Order of Odd-Fish), Stephen Palmer (The Factory Girl Trilogy, Memory Seed, Beautiful Intelligence), Justina Robson (The Quantum Gravity series, Natural History, Switch), Tricia Sullivan (Occupy Me, Dreaming in Smoke, Maul), and Lisa Tuttle (The Curious Affair of the Somnambulist and the Psychic Thief, The Mysteries, Windhaven (with George RR Martin)).

I have recently edited a new anthology of science fiction and fantasy stories about fantastical flora. The book, Improbable Botany, features authors who between them have won the Arthur C Clarke, British Science Fiction Association, John W. Campbell Memorial, Philip K. Dick, Nebula and Prometheus Awards, and been nominated for many more. The writers are: Cherith Baldry (co-author of the New York Times best-selling Warrior Cats series), Eric Brown (The Kings of Eternity, the Langham and Dupré crime novels, the most recent of which is Murder Take Three), James Kennedy (The Order of Odd-Fish), Ken MacLeod (Intrusion, The Corporation Wars), Simon Morden (the Metrozone series, Down Station / The White City), Adam Roberts (The Real-Town Murders, The Thing Itself), James Kennedy (The Order of Odd-Fish), Stephen Palmer (The Factory Girl Trilogy, Memory Seed, Beautiful Intelligence), Justina Robson (The Quantum Gravity series, Natural History, Switch), Tricia Sullivan (Occupy Me, Dreaming in Smoke, Maul), and Lisa Tuttle (The Curious Affair of the Somnambulist and the Psychic Thief, The Mysteries, Windhaven (with George RR Martin)).

As part of the project I have interviewed all of the contributing authors, not just about Improbable Botany but about their writing in general and much more besides. Below is my interview with Adam Roberts.

Improbable Botany is being published by Wayward, a London-based landscape, art and architecture practice, and funded via Kickstarter. The book is illustrated by Jonathan Burton (The Folio Society, Penguin Books, Random House). One of the Kickstarter bonuses is a free e-book which will include all the interviews, though they will also be published individually in various places. The only time they will ever appear all together is in the Kickstarter e-book. The Kickstarter also offers the opportunity to acquire A2-sized art prints of all six of Jonathan Burton’s interior illustrations, as well as his breathtaking cover art. Click here to see Amazing Stories’ exclusive preview.

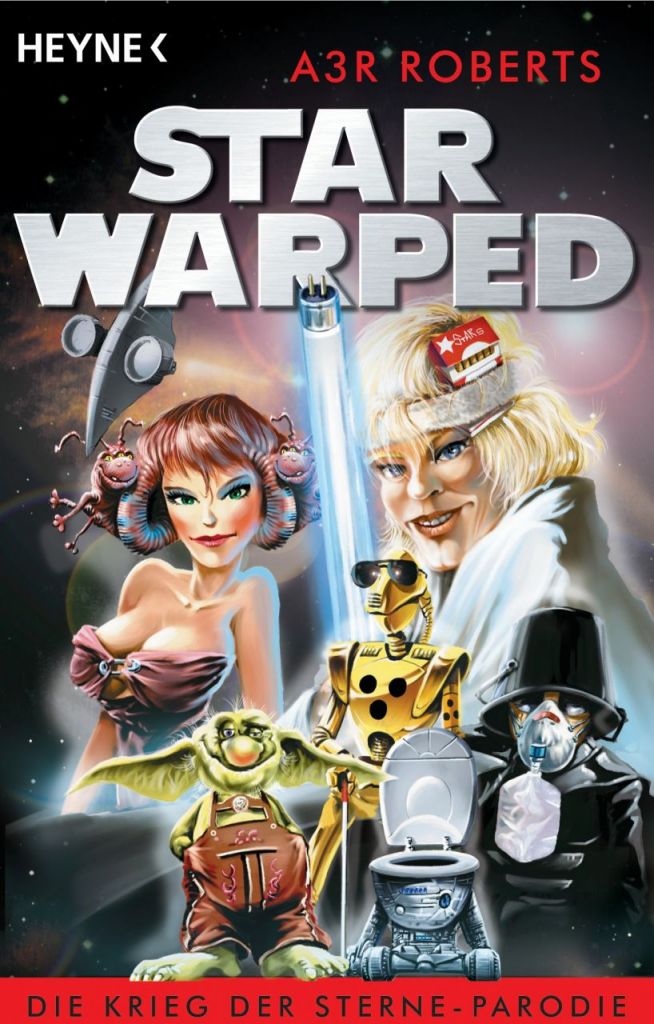

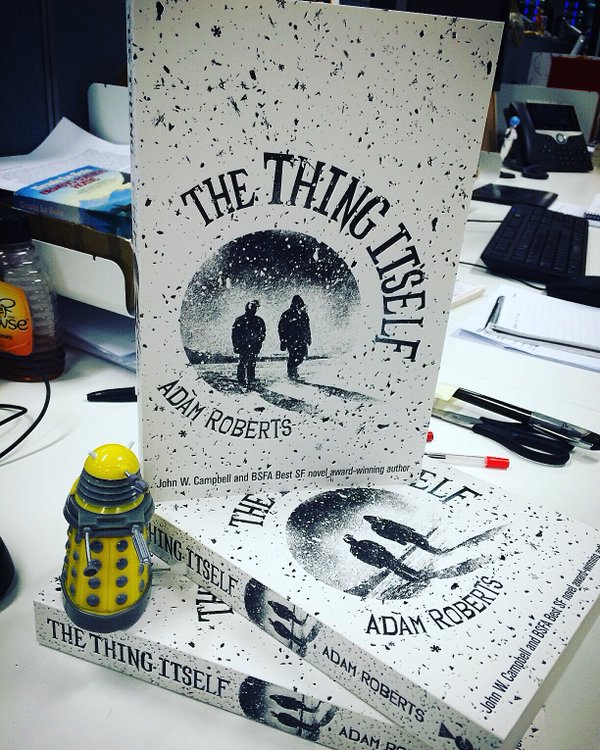

Adam Roberts is the author of 17 novels, 8 parodies, at least as many collections and novellas, and several volumes of non-fiction, including The History of Science Fiction (Palgrave). His novels range from his Arthur C. Clarke Award-nominated debut, Salt (2000) through Jack Glass (2012) to most recently, The Thing Itself (2015). Robert’s latest novel, The Real-Town Murders, is published in August. On top of this exhaustive publishing schedule, Roberts is also Professor of 19th Century Literature at Royal Holloway, University of London.

*

Gary Dalkin for Amazing Stories: ‘Black Phil’, your story in Improbable Botany, packs a huge amount into 20 pages. It combines the scientific, the political and the personal in a way which is ultimately very moving, and does so while gradually revealing to the reader a startlingly imagined near future earth. There is a lot of specific detail in the story and I’m wondering what your approach to writing a piece like this is, how much do you have planned out before you begin writing, and how much comes to you through the writing process? I’m asking this in part because I’m wondering how quickly you write, given you are a prolific author of highly imaginative, intricately constructed novels and have a day job as a professor of literature as well.

Adam Roberts: My approach to writing has changed, I suppose. When I was starting out as a writer I would generally plan things out fairly carefully; now I have more technical fluency, and can trust my hands to produce more of what’s needed if I let them loose on the keyboard. Not entirely though. It’s a balance, as with so much of life. If a writer maps every beat of every chapter in a detailed plan before she ever writes a word, the danger is that the actual writing turns into a chore, merely filling in the blocks in the grid, and if the writer gets bored writing then that tends to communicate itself to the reader. On the other hand, simply diving in with no sense of where you’re going or how the story is going to unfold, in my experience, will result in something too baggy and freeform, understructured and messy. So the praxis for me is threading a path between those extremes: having a sense of the overall shape of the thing, and which spots I definitely want to hit as I go, but working out some of the specifics as I write the first draft, to keep at least elements of it fresh. With short stories the process is a little different to novels: plot is constrained by the shorter space, so there’s a greater need for other things to hold the whole together – a governing metaphor, for instance, that can be unpacked and explored, provided it’s eloquent enough. In ‘Black Phil’ I was working with blackness as a colour and blackness as a mood, which meant that the story needed to make a certain kind of emotional sense, and the other elements were rather subordinated to that.

GD: ‘Black Phil’ was written to commission, the brief being that there had to be some element of strange or speculative botany involved. Without saying too much, the title itself does allude to the botanical heart of the story – that darker chlorophyll is more efficient at processing sunlight – would it be correct to say that was the first element you settled on, and that everything in the story grew around that? Ideas around different aspects of blackness? And beyond that, do you find it easier to write a story with a completely blank canvas, free of an editorial requirements, or does a commission help in providing a nucleus to develop a story around?

AR: The initial idea germs for stories come from all sorts of places. Here, I think it was the media reporting around the star KIC 8462852, which has been strangely dimming. It’s probably not because a Dyson sphere is being constructed around the star, but it’s fun to speculate. So it got me thinking: what other signs might we be able to observe, long-distance, that indicated intelligence was living near a star? And that got me thinking about chlorophyll. Green is on the opposite side of the colour wheel from red. The reason our plants are green is because they evolved the mechanisms of photosynthesis when our sun was a more reddy-orange colour than it now is. It hasn’t changed, even though the light from our star has become whiter over time, because it still does the job; but if we wanted to maximise the efficiency of photosynthesis we might tweak chlorophyll to be much darker, even black. Melanophyll. And if we were to do that, planetwide, it would send a signal to any interested parties who happened to be watching in space that we had evolved, as a species, to quite a technologically sophisticated level.

GD: Science fiction, especially hard science fiction, is sometimes criticised for placing such an emphasis on the ideas and science that character gets overlooked. Yet ‘Black Phil’ is an intensely human story, real personal consequences being intimately entwined with the consequences of scientific development. Is striking this balance between character and idea-based fiction something which comes naturally to you, something you consciously strive for, or somewhere in between? I’m asking because your work is idea driven to a remarkable degree, you seem to have an insatiable appetite to explore through your fiction an endless stream of scientific and fantastical ideas. But on the other hand, you are Professor of Nineteenth Century Literature at Royal Holloway, University of London, an area we think of as being a much more character-driven literary world than science fiction…

GD: Science fiction, especially hard science fiction, is sometimes criticised for placing such an emphasis on the ideas and science that character gets overlooked. Yet ‘Black Phil’ is an intensely human story, real personal consequences being intimately entwined with the consequences of scientific development. Is striking this balance between character and idea-based fiction something which comes naturally to you, something you consciously strive for, or somewhere in between? I’m asking because your work is idea driven to a remarkable degree, you seem to have an insatiable appetite to explore through your fiction an endless stream of scientific and fantastical ideas. But on the other hand, you are Professor of Nineteenth Century Literature at Royal Holloway, University of London, an area we think of as being a much more character-driven literary world than science fiction…

AR: I’d prefer not to have to dichotomise these two things, but you’re probably correct that they’re too often opposed in genre. I’m not sure what can be done about this, beyond noting that I have always taken SF to be a fundamentally metaphorical mode of art, not only in the sense that it very often literalises metaphors, but also in a structural, technical sense (that sense that distinguishes, via (Roman) Jakobson, between the poetic sense-of-wonderful leap of the metaphor on the one hand, and the plodding, one-thing-then-another-thing connectivity of metonomy on the other). The props and toys, the conceits and extrapolated technologies of the genre are almost always metaphorical, and metaphors are what we live by. It seems to me, as a writer, that this provides a way of mapping the novums of SF onto the character-based and formal aspects of what is sometimes called ‘literary’ fiction.

GD: I’m not sure anything much can be done about it, given the very literal, superficial way the genre is often viewed, specially by writers who spend much more time watching it, rather than reading it. A decade or so back you wrote half a dozen genre comedies, spoofing The Lord of the Rings, The Matrix, Doctor Who and others. At the same time you were penning an exhaustive history of the genre – The History of Science Fiction – as part of the Palgrave Histories of Literature series. That’s a rare facility, the ability to both see humour in the genre and spoof its failings, yet still take it seriously. How important is humour to you? Your novels are clearly informed by a deep knowledge of the genre, and of literature in general, but also it often seems, by a rather playful spirit.

AR: Well laughter is important to me, possibly over-important, for reasons that probably don’t bear too much interrogation, to do with the sort of person I am, the (more-or-less repressed, English) culture in which I grew up and so on. But I would answer your question by following-on from what I’ve just said. SF, I think, is the bone thrown into the sky that suddenly, sense-of-wonderfully, somehow *rightly*, turns into a spaceship. That transformation is a metaphorical one, in Jakobson’s terms: something marvellous and unexpected, something that could not be predicted ahead of time (in contrast to metonymic sequences of plot, or association, or logic, of the A to B to C kind … which can always be predicted). And that trajectory, that delightful unexpectedness, is also the structure of a joke. The form of a joke is to follow along a particular extrapolation of a premise and then suddenly to twist in an unexpected direction. A man walks into a library and says: “I’ll have fish and chips please!” And the librarian looks at him, puzzled, and says: “but … but this is a library.” “Oh! I’m sorry!” says the man, and then leans-in and whispers “I’ll have fish and chips please …” It’s that knight’s-move shape, the unanticipated shift in direction, that makes the joke; and that’s the same ‘shape’ that makes SF work.

I really do see SF and laughter as structurally equivalent: not, I should stress, that I think SF needs always to be funny, or to make people laugh, because clearly it doesn’t, but that something in the work needs to include that unexpected release, that joy.

GD: I hadn’t thought of that before, that the sense of joy, what’s sometimes called the ‘sense of wonder’ in science fiction, does come from the unexpected, just like humour. Of course, push it too far, as Hollywood does all the time, and expect the reader or audience to accept too much of the unexpected, and one ends up laughing at, rather than with. It can be a fine line.

GD: I hadn’t thought of that before, that the sense of joy, what’s sometimes called the ‘sense of wonder’ in science fiction, does come from the unexpected, just like humour. Of course, push it too far, as Hollywood does all the time, and expect the reader or audience to accept too much of the unexpected, and one ends up laughing at, rather than with. It can be a fine line.

But building on that, it does seem, looking back through your published novels, that the only thing a reader might expect from you in future is the unexpected. Each book has been so distinctively different from its predecessors, and that fits completely what you’ve just said about “something marvellous and unexpected”. Would you ever really surprise us by writing a series? Could you, temperamentally, write a series, or would you get bored after the first volume and want to move onto something completely different?

AR: Writing a series: hmm. I think an author really does need to beware of becoming trapped, of settling into a rut, even a success-rut. Conan Doyle grew to hate Sherlock Holmes, whom he felt distracted readers from all the other things he was writing (really he wanted to be known as a writer of historical fiction. Mind you, I’ve read some of his historical novels and they’re turgid). But the thing about that is: it’s possible to become trapped by the insistence that one is not going to be trapped, if that doesn’t sound too Zen. I’ve written a whole bunch of different novels less by design, and more because I get bored and restless and generally want to do something new. But it’s certainly possible for the ‘never do a sequel’ thing has become procrustean. So I decided to write a sequel – my latest novel from Gollancz is a near-future whodunit set in Reading, via Hitchcock, called The Real-Town Murders. I’m presently writing a sequel, working title The Punctured Thumb. Now, I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking: “ah, but if Adam’s shtick is doing something different each time, and he’s never before published a sequel to one of his own books, then publishing a sequel to one of his own books is doing something different!” But if you think of it like that, there’s no escape from my saṃsāra.

GD: The Real-Town Murders is out in August. What can you reveal about it now, and specifically, what’s the Hitchcock connection?

AR: The germ of the book was an account I came across of a film Hitchcock never got around to making. He had the idea for a pre-credits sequence, set (this was the early 1970s) in a fully automated, robot-only car factory. He said the camera would follow the whole process of a car being made: you’d see the raw materials being delivered by automated truck; the camera would work its way along the assembly line as robots fitted the body panels together, inserted the engine, put in seats and so on. No people around at all; everything automated. At the end of this sequence the camera would follow the now completely built car out the other end of the factory, down a ramp to join a long line of similarly assembled autos. A man would come along with a clipboard to check the build. He would open the boot of the car (maybe the word Hitchcock used was “trunk”, I’m not sure) and …. inside would be a dead body. “If only I could figure out how that dead body got into that car,” Hitchcock said, “I would make that movie.” But he never did, and so the movie was never made.

AR: The germ of the book was an account I came across of a film Hitchcock never got around to making. He had the idea for a pre-credits sequence, set (this was the early 1970s) in a fully automated, robot-only car factory. He said the camera would follow the whole process of a car being made: you’d see the raw materials being delivered by automated truck; the camera would work its way along the assembly line as robots fitted the body panels together, inserted the engine, put in seats and so on. No people around at all; everything automated. At the end of this sequence the camera would follow the now completely built car out the other end of the factory, down a ramp to join a long line of similarly assembled autos. A man would come along with a clipboard to check the build. He would open the boot of the car (maybe the word Hitchcock used was “trunk”, I’m not sure) and …. inside would be a dead body. “If only I could figure out how that dead body got into that car,” Hitchcock said, “I would make that movie.” But he never did, and so the movie was never made.

So I thought to myself: that’s a good starting place. And it gave me the chance to write a whodunit and thriller with as many Hitchcockian touches as I liked.

The book was originally called The R!-town Murders, because the future Reading in which it is set has rebranded itself to make itself cooler and more attractive to residents (unavailingly, of course): “My town! Your town! R!-TOWN!!” But my editor at Gollancz, Marcus Gipps, told me that bookscan can’t cope with book titles that have exclamation marks in strange places, so we had to rename it. This, though, is better than the title I originally wanted, which Marcus absolutely noped. Just as Hitchcock tried, and failed, to get the studios to release North by Northwest under the title The Man Who Sneezed in Lincoln’s Nose, so I would have loved to call this novel The Woman Who Sneezed in Shakespeare’s Nose. Alas, it was not to be.

…is a freelance editor, writing consultant and story structure expert. To find out more, including hiring me to work on your writing project, read my profile or visit my website, To The Last Word.