by Foz Meadows

This article originally appeared on the Blackgate magazine website. For a full explanation of its journey, please see the notes below.

The Axis trilogy (published in the US as the first three novels of The Wayfarer Redemption)

Owing to recent political developments, I’ve been thinking a lot recently about politics in SFF, not just as a general concept, but in relation to my own history with the genre. So often when we talk about politics in SFF, it’s in the context of authors – rightly or wrongly, consciously or unconsciously, skilfully or unskilfully – conveying their personal views and biases through the text, the whens and hows of doing so and why it matters, depending on the context. As a corollary conversation, we also talk a great deal in personal terms about the importance to readers, and particularly young readers, of representation; the power of seeing yourself, or someone like you, in multiple sorts of narrative. These are all vital conversations to have, and to continue having as both culture and genre evolve. Yet for all its similar importance, I haven’t often seen discussions about the ways that SFF informs our concept of politics in the more institutional sense: the presentation of different systems of government, cultures and social systems within narratives, and the lessons we take from them.

Which is, to me, surprising, because as far back as I can remember, I was always aware of the role of politics in genre stories, even if I couldn’t always articulate that knowledge at the time. At the very start of high school, Sara Douglass’s Axis trilogy became my entry point to the world of adult (as opposed to YA or middle grade) fantasy. In hindsight, there’s a great deal in that series – and in the sequel trilogy, The Wayfarer Redemption – that I now find deeply unsettling, but which, as a tween, I absorbed uncritically. But at the same time, I also recognised the predatory, insular monotheism of Artor the Ploughman as a deliberate analogue to certain toxic expressions of Christianity, its displacement of and propagandising about the Icarii and the Avar reminiscent of lies told about various native populations by white invaders. I wasn’t yet literate enough to identify the racial stereotypes underpinning the Avar in particular – a dark-skinned race who claimed to “abhor” violence, yet were externally said to “exude” it – but something in that description still unsettled me; I remember feeling strongly that it was an unfair characterisation in a way that went beyond the story, but couldn’t explain it any more than that.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

A few years later, I started reading Raymond E. Feist at the recommendation of my then-group of geeky friends, all of whom were fans. I was still years away from coming to any sort of cogent understanding about tropes and their place in genre; nonetheless, while reading A Darkness at Sethanon, I was struck by one of the most important realizations about narrative of my young life. In the book, the heroes had just encountered a powerful dark army and were rushing to tell their allies of the unprecedented danger – yet when they reached the nearest stronghold, the commander in charge didn’t believe their claims that an ancient evil, long-prophesied and rooted in magic, was on his doorstep. My first reaction to his doubt was a surge of outrage: having just “seen” the army myself through the eyes of the protagonists, I knew the threat – to say nothing of magic itself – was very real. How could anyone doubt them? I thought to myself. It’s so obviously true!

Raymond E. Feist’s Riftwar Saga, including A Darkness at Sethanon

And this is when the epiphany struck. Thoughts churning, I realized in the very next breath that, from the commander’s perspective, the truth wasn’t obvious at all, and that if someone in real life ever approached me with a similarly outlandish claim, I’d likely dismiss them, too. I was – and still am – an atheist: I didn’t believe in gods and magic, just like the doubting commander; the only difference between us was that I had an omniscient perspective on the truth of his world that he, as an individual, lacked. I’d started reading the story in large part because I wanted to suspend disbelief in the non-existence of magic, but until that moment, I hadn’t considered that doing so involved a non-superficial shift in my perspective, not just of what was possible, but of people. For the first time, I realized the power of stories to make the reader sympathize with attitudes beyond their own, and the specific ability of SFF as a genre to accomplish this by retelling familiar dilemmas in unfamiliar settings.

Looking back, that moment was when I first started to become a critical reader, and to wonder at the relationship between stories and politics. My conclusions were often flawed or incomplete, and I regularly missed parallels which stand out to me now, but everyone starts that particular lesson somewhere, and for me, it was Raymond E. Feist.

Not long afterwards, on the recommendation of the same, predominantly male group of friends, I started reading Terry Goodkind’s Sword of Truth series. Up until that point, most of the fantasy I’d read was female-authored, in large part because I grew up in Australia, and the Australian fantasy market has long been female-dominated in a way that the American and UK markets aren’t. That being so, and unlike many other readers from different traditions, I wasn’t used to SFF stories where women routinely experienced sexism and gender-based violence, not as something clearly rejected by both the narrative and the characters, but for shock value. Even now, I find this a difficult distinction to articulate, and I want to be clear that, in addition to being a choice made by writers of all genders, it’s also frequently a Your Mileage May Vary Issue. Certainly, I’d read stories which featured the rape or sexual assault or women – Anne McCaffrey’s Acorna series springs prominently to mind, while the amount of rape present in some of Sara Douglass’s work appalls me in hindsight – but Goodkind’s was the first series I read where the repeated motif of rape and abuse made me feel alienated by the narrative.

The number of times that Kahlan was almost raped, with frequently graphic nearness, while other women suffered her intended fate without rescue, made me acutely aware of the way that a story could strongly convey a specific idea without ever stating it plainly – in this case, the idea that rape was the single worst, most horrific thing that could ever happen to a woman. The books made me uncomfortable in other ways, too – not just narratively, but politically. Where reading Feist sparked my critical awareness of narrative empathy and the power of stories to show the reader perspectives beyond their own, reading Goodkind taught me that it was possible to question or disagree with ideas that the story – and, by proxy, the author – portrayed as being morally correct.

The first novels in Terry Goodkind’s 17-volume Sword of Truth series

In Goodkind’s setting, a POV character was horrified by the idea that women in a town whose primary institution was devoted to magical study were deliberately falling pregnant to the male mages, so that the institution would, as per long-standing custom, pay them a generous stipend to help raise the subsequent magically-gifted children. This character, on coming to a position of power in the institution, therefore made it his first order of business to cancel the stipend forever: that way, it was argued, the women who’d been mooching financially off the magical institution would have no further incentive to do so, and the cynical practice of breeding for magic would stop. In text, it was presented as a sensible, moral reform for the (sympathetically-portrayed) character to make – a portrayal helped by its pairing with a clearly necessary shift in magical practice, one that changed the yardstick used to prove a mage’s readiness to advance away from “how much pain this person can endure” and towards “how much have they grown as an individual.”

I agreed with the latter decision – the traditional test was clearly horrific – but thought the former decision was deeply flawed. However cynically the stipend system was being abused both the townswomen and the mages alike (though only the women seemed to be censured for it), removing it wholesale meant that the existing children would suffer as their mothers were plunged into poverty. Though the townsfolk protested the change, the character considered this consequence unimportant – and as their opposition was portrayed as being just as backwards as the mages’ rejection of the magical reform, it was clear that the narrative itself endorsed the character’s decision.

Even as a teenager, I recognized the similarity of the argument put forward by Goodkind’s character to that of real-world politicians angry at the supposed abuse of benefits systems by unwed mothers, a claim to which I was actively opposed. Though I’d noticed plenty of similarities between SFF stories and real historical events before then, such as the religious and colonial aspects of Sara Douglass’s work, Goodkind was first time I’d recognized such a direct paralleling of modern politics. Reading Feist, I’d sympathized with the faith of religious characters despite being an atheist: I’d done it before in other books, but Feist was the first time I’d noticed. Realizing this not only helped me rethink some of the preconceptions I’d had about real-world religious beliefs, but gave me a fuller, more nuanced appreciation for a character I’d initially despised. Reading Goodkind, however, was a different experience: yes, the story was still asking me to be sympathetic to a perspective other than my own, but it was doing so in a way that required me to disregard my existing empathy for another group, while casting aspersions about the inherent morality of a group to which I belonged.

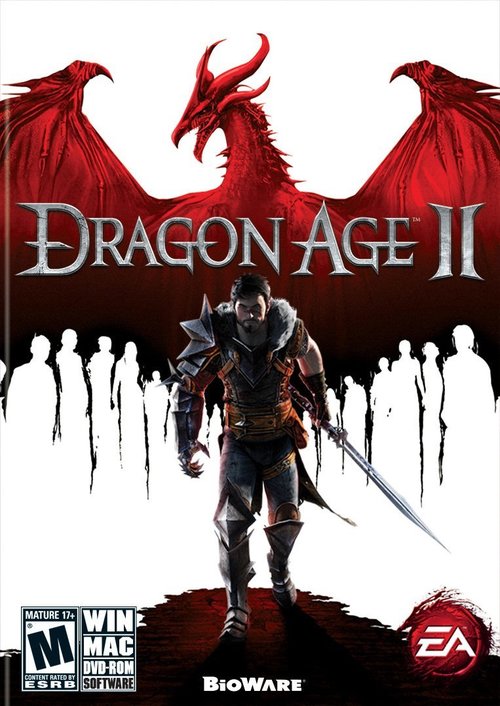

Earlier this year, in the course of sharing my love for Dragon Age 2 on Twitter, I ended up in conversation with a UKIP supporter who, to my complete astonishment, was also a fan of the game. I say astonishment, because UKIP, for those unfamiliar with that party’s policies, is avowedly anti-refugee and frequently homophobic, while DA2 is, rather undeniably, a game about a queer refugee who works hard to improve their new city. When I pointed this out, the UKIP supporter suggested I was naïve for seeing any similarity between the politics of the game and those which existed in the real world: to him, Hawke’s flight from Ferelden in the wake of the Blight and subsequent residence in Kirkwall was wholly understandable, while the plight of Syrian refugees fleeing war and turmoil and wanting residence in the UK was not.

We didn’t talk for long, but I’ve often thought about that exchange since, wondering at the sort of cognitive dissonance necessary to enforce that sort of narrative compartmentalization; to fail to even acknowledge the similarities between the real and the fictional. Perhaps he considered Hawke an obviously “good” immigrant, one who made a clear effort to benefit his new home, and therefore felt the character an exception to the rule. Perhaps he thought that Hawke’s blood-ties to Kirkwall nobility meant they weren’t really a refugee or immigrant at all, but a rightful citizen forced into unfair struggle to reclaim their birthright, and was therefore exempt from criticism. Perhaps he felt that the demonic Blight, an unambiguously evil, nation-killing horror, justified fleeing one’s country in a way that unmagical civil war does not. Perhaps it was simply that the default Hawke is a conventionally attractive white man who speaks fluent English, and therefore was not subject to the same automatic censure as foreign brown people with accents. Perhaps it was none of these things, or a combination of all of them; or perhaps he’d simply accepted the game as fiction without considering what that fiction meant. But either way, his lack of awareness of politics in narrative is not unique – and that, to me, is both fascinating and frightening.

Dark lords, demons, genocidal invading aliens and other such unambiguous evils are a narrative staple of SFF: indeed, they’re fundamental to many of our favorite renditions of the hero’s journey. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t still political complexity to be found in such stories, to say nothing of ordinary political systems. Even in worlds where an ultimate, inherent morality is exemplified by a struggle between Dark and Light, Good and Bad, the actions of people are seldom cast in such a binary mould – and yet, I suspect, it’s easy to trick ourselves into thinking otherwise, because if the good guys are clearly on the side of the (demonstrably real) angels, then who are we to question their methods? As readers, we’re omniscient: we know, in a way the characters seldom do, exactly why their actions matter, what the outcome is going to be and how few paths there really are to achieving it. From that perspective, it’s comparatively easier to accept that the end justifies the means, because we’re in the best, most objective position possible to weigh motive against execution, intention against consequence, and to view the whole chain of events at a remove. We know the characters better than they know themselves, and that makes us judge them differently than if we were there beside them, working through the same problems with the same set of limitations.

The way we’re otherwise forced to do in life.

Since the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency, there’s a particular social media status I’ve seen circulating in various places, though I think this tweet is the original:

It’s something I’ve seen treated with eyerolls and irritation by people I know to ultimately support the sentiment – i.e. that dictatorships, imperialism and fascism are worth fighting against – on the basis that it’s somehow a dumbing down of the current political situation; if people can only understand that what’s happening now is bad by relating it to stories, this logic says, then they probably don’t understand it at all. And in one sense, I understand that perspective. For those born with social privilege, reading about oppression and oppressive systems in stories is the only way to “experience” that sort of prejudice. That being so, if your first reaction to the jarring post-election spike in hate crimes (for instance) is to relate it to a story rather than to fear for yourself or others, then you likely don’t belong to an at-risk group. In a perfect world, we wouldn’t need stories to act as emotional dry-runs for caring about different types of people, because our empathy would already natively extend to everyone. But we don’t live in that world; because if we did, somewhat paradoxically, we’d have less urgent need of its empathy, as its unequivocal presence would make it much harder for us to discriminate in the first place.

Which is precisely why stories matter; why they’ve always mattered, and will continue to matter for as long as our species exists. Stories can teach us the empathy we otherwise lack, or whose development is railroaded by context, and yeah, it’s frustrating to think that another person can’t just look at you, accept what you are, and think, human, different to me in some respects but fundamentally as whole and as worthy of love, protection and basic rights as I am, but you’ve got to understand: we’re a bunch of bipedal mammals with delusions of morality, a concept we invented and which we perpetuate through culture and manners, faith and history and memory – which is to say, through stories, which change as we change (though we don’t always like to admit that part), and in that context, the value of the impossible – of SFF as a genre – is that it gives us those things in imaginary settings, takes us far enough out of the present that we can view them at a more objective remove than real life ever allows, and so get a better handle on them than our immediate biases might otherwise permit.

Stories reflect us, and we reflect them back at themselves, like one of Terry Pratchett’s witches standing at the heart of a room of mirrors: humanity all the way down. In the midst of real-world politics and their ever-evolving consequences, our narrow individual perspective is that of a character denied the author’s omniscience: we don’t know what to make of the pattern of things – if there even is a pattern – or where events are headed, and yet we still have to choose what to do in the moment. And so we look outside ourselves, to stories where we do really know what’s happening, to characters in whose hopes and fears we recognise our own. We might make jokes and memes about it, buy little rubber bracelets stamped with WWBD (What Would Buffy Do?) and laugh at our preoccupation with people who don’t really exist, but when the hammer falls and our own words fail us, theirs remain.

I must not tell lies.

We are not things.

If we burn, you burn with us.

Right now, we don’t need a Jedi Master to tell us that fear leads to anger, anger to hate, and hate to suffering: that’s not an abstract mystical tenet, but the bedrock of our current political reality. For the past few years, the Sad and Rabid Puppies – guided by an actual neo-Nazi – have campaigned against what they perceive as the recent politicization of SFF as a genre, as though it’s humanly possible to write a story involving people that doesn’t have a political dimension; as though “political narrative” means “I disagreed with the premise or content, which makes it Wrong” and not “a narrative which contains and was written by people.”

Right now, we don’t need a Jedi Master to tell us that fear leads to anger, anger to hate, and hate to suffering: that’s not an abstract mystical tenet, but the bedrock of our current political reality. For the past few years, the Sad and Rabid Puppies – guided by an actual neo-Nazi – have campaigned against what they perceive as the recent politicization of SFF as a genre, as though it’s humanly possible to write a story involving people that doesn’t have a political dimension; as though “political narrative” means “I disagreed with the premise or content, which makes it Wrong” and not “a narrative which contains and was written by people.”

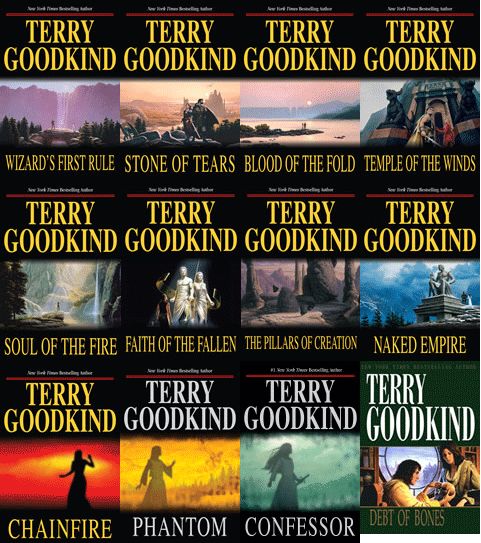

And so I think about the UKIP supporter who empathized with a fictional refugee but voted to dehumanize real ones; about the millions of people who grew up on stories about the evils of Nazism, but now turn a blind eye to swastikas being graffitied in the wake of Trump’s election; of Puppies both Sad and Rabid who contend that the presence of politics in genre is a leftist conspiracy while blatantly pushing what even they call a political agenda; about fake news creators and the Ministry of Truth; about every f***ing dystopian novel whose evocation by name feels simultaneously on the nose and frighteningly apropos right now, because we shouldn’t have to cite The Handmaid’s Tale to explain why Mike Pence and Steve Bannon (to say nothing of Trump’s infamous comments) are collectively terrifying, and yet see above re: unempathic bipeds of failure, forever and always; and yet –

Terry Pratchett once wrote: “Humans needs fantasy to be human. To be the place where the falling angel meets the rising ape.” That line has always felt powerful to me, but moreso now than ever before. I keep finding myself with quotes and fragments stuck in my head, pieces of other people’s writing that remind me of a political reality whose depth and breadth of awfulness I’m struggling to process. Sometimes those fragments fill me with despair, but in others I find strength, and heart, and hope. From their oldest mythological underpinnings to their newest CGI iterations, tales of science fiction and fantasy have always reminded us of our empathy in times when we need it most; have always helped us understand our single solid world through airy worlds adjacent, separated from us only by the tip of Will Parry’s subtle knife or Nakor’s bag of oranges.

In these times, may stories be a light in dark places, when all other lights go out.

***

Editorial Comment and Addenda

The History of This Article

The article was originally proposed by Ms. Meadows to the editor of BlackGate magazine, John O’Neill. He accepted, Foz wrote, the article was published on 12/7/2016. I read it on the 9th of December, commented positively and was shortly contacted by Mr. O’Neill via email, asking if I would be interested in giving a home to the article, owing to Mr. Beale’s objections. Mr. Beale had previously been a contributor to Blackgate and objected strenuously to Ms. Meadows’ use of the term “neo-Nazi”. Mr. O’Neill offered to ask Ms. Meadows to re-write a portion of the piece or, if she chose not to, to take the article down. Ms. Meadows initially contemplated doing so (her proposed changes are included below) but ultimately decided not to change the wording because, as she stated in an email reprinted on File 770 –

“…he (John O’Neill) asked if I’d consider changing my wording as a personal favour to him. I didn’t want to do that for a number of reasons, not least because we’re at a point in history where refusing to acknowledge the neo-Nazism of the alt-right, with which VD is openly affiliated, is a major contributing factor to its normalisation. To me, this was a statement worth defending.

Owing to Ms. Meadows’ being domiciled in Australia and Amazing Stories being headquartered in the northeastern US, as much as 12 hours transpires before communications back and forth are responded to. I requested a day or so to do some research and failed to contact Mr. O’Neill when Ms. Meadows agreed to the short delay. As a result, Mr. O’Neill truncated the article and placed a link to Amazing Stories, which continues to go “nowhere” until the article is actually published here.

A decent bit of research regarding the Alt-Right, neo-Nazism, definitions and ideologies was conducted over the weekend. That research turned up the following (in summary form):

1. Mr. Beale’s personal definition of Nazism, and by way of derivation, neo-Nazism is strictly limited to the political ideology professed by the National Socialist German Worker’s Party that rose to power in Germany prior to World War II. Since he is not German, not a member of the NSDAP, his claim is that he can not be referred to as a neo-Nazi. Note that Nazism was not limited geographically to Germany and its ideology not limited to one political party in one country at one point in time.

2. Mr.Beale has self-identified as “Alt-West”, owing to his Native American and Mexican heritage.

3. The Alt-Right movement has been identified as being associated with nationalism and white supremacy, of which neo-Nazism is a strain. (At a recent rally in Washington DC, one of the leading proponents of the Alt-Right movement, Richard B. Spencer, referenced Nazi propaganda; reportedly, neo-Nazis and white supremacists have provided security at some of his appearances.)

4. The Alt-Right “movement” professes to have no leaders, no formal philosophies and no formal identification. This is designed as a tactic to shield them from being more closely identified with marginalized political movements, such as white supremacy and neo-nazism. An examination of the movement’s positions on a wide variety of issues find that they are in close alignment with such groups. Changing the name does not change the philosophy. The Alt-Right wants its opponents to have to play whack-a-mole and waste its time arguing over names instead of ideologies.

5. Numerous articles in both the mainstream press and on-line draw a connection between the alt-right and neo-nazism, and the alt-right and white supremacy, sufficient for any reader to come to the conclusion that they they are all one and the same, or nearly so. At best, different branches of the same over-riding philosophy.

6. “Neo” is used to suggest both “new” and “like”: a “neo-conservative” is a person holding modified conservative views. A “neo-fan” is a newly minted fan. It is our understanding that the term “neo-Nazi” refers to both the “new Nazi” movement and to belief’s that are greatly similar to Nazi philosophies; a “neo-Nazi” is an individual professing Nazi-like beliefs.

***

I have asked Ms. Meadows for permission to publish her modified version here as well. Owing to differences in time zones, we have not heard back at the time this piece was published. If permission is granted, we will publish it here.

Based on wikipedia’s definition: “The term neo-Nazism can also refer to the ideology of these movements.[2]

Neo-Nazism borrows elements from Nazi doctrine, including ultranationalism, racism, ableism, xenophobia, homophobia, antiziganism, antisemitism, and initiating the Fourth Reich.”

using “neo-Nazi” is not incorrect.

ChoTime: that’s what we’re finding all over the place. Hundreds, if not thousands of instances, both casual and professional, using the term in exactly the same way Foz did.

It’s like the word “fascist” or even “racist.” There’s an ideological fight over the meaning of the word, essentially over how circumscribed it should be. And there has to be, because once the definitions are accepted, the arguments follow clearly. You know?

Thanks for hosting this article, by the way. Bookmarked!

yes, but the alt-right is trying to define all of these buzz words in a manner that points away from them…and it won’t work because word – meaning broaden over time, they don’t narrow.

What I’ve found is that the fight over the definitions means no dialogue between groups is possible. So no one ever gets the chance to argue things logically.

yes, but, on the other hand, use of that technique – deflection by way of definition – clues one in immediately to the fact that they are dealing with an asshole who is not interested in dialogue

Now that is a great point!

I’m getting ready to close this discussion thread….

Alright, enough.

If you want to discuss male bottoms, or any bottoms belonging to an animated species, why not go visit Chuck Tingle’s Amazon review page…

Well, I see that there’s been a lot of violation of our general comment policies going on during my absence.

I’ll not take anything down or ban anyone over it, but I will remind you ALL that our policy requests that one address the ISSUE not the INDIVIDUAL.

By way of near-perfect example, please read Astrid’s post.

And for the edification for all having this discussion, here’s a bit of interesting info:

The Associated Press issued guidelines for how to treat the subject of “Alt-right” in their articles.

“Usage

“Alt-right” (quotation marks, hyphen and lower case) may be used in quotes or modified as in the “self-described” or “so-called alt-right” in stories discussing what the movement says about itself.

Avoid using the term generically and without definition, however, because it is not well known and the term may exist primarily as a public-relations device to make its supporters’ actual beliefs less clear and more acceptable to a broader audience. In the past we have called such beliefs racist, neo-Nazi or white supremacist.”

Note that last line: the AP has, in the past, treated the term “neo-Nazi” in exactly the same way Ms. Meadows did in her article – as an interchangeable term for racist, white supremacist beliefs.

The terms “Nazi” and neo-Nazi have come to be used in the same manner as we used to throw around “commie”, a term of derision for beliefs one considers ill-informed at best and nauseating at worst.

From what I understood neo-nazis were associated with skinheads, bikers, and prison gangs. At least in the US. None of them would let a person with poc blood join. Anyway, calling opponents to immigration racists and neo-nazis did not help remainers and democrats.

Finally, there’s obviously a huge difference between one fictional refugee in a game and tens of millions of refugees and economic migrants moving to Europe. The later is causing a lot of backlash that will only get worse.

I’m genuinely surprised Blogspot continues to give him a voice even after all the doxing and stalking.

Thank you, Foz. I am so glad that Beale has not silenced the edge in your voice.

I said on twitter the other day that “Man is the animal that tells stories to make sense of the world.” I think your essay suggests we have some agreement on that topic.

Still a very good article, so I’m very glad to see it here. How about people respond to the whole thing, and not just the 5 words that upset some guy in Italy?

Stellar “research” there, sparky.

1. “If some mainstream Fake News sites call them Nazis, it must be so! And it must be true that Trump is an insane genocidal bigot worse than Hitler, too!”

2. “White nationalism is the same as white supremacy is the same as Nazism!”

One doesn’t even have to be white to be supportive of white nationalism. Personally, I’m Jewish, as are many of Vox’s readers. In fact, being a Russian Jew, I have many ancestors that fought actual Nazis.

Anywho, your shoddy, dishonest “research” won’t save you from a lawsuit, which you have now incurred. Good luck finding a lawyer around Christmas!

I’m a mallard, damn you! Not a duck!

If Mr. Beale does file suit against Foz, I will *happily* contribute to her legal fund.

And I don’t understand Beale’s anger. The dark authoritarian white supremacist President Elect of his dreams is going to be elected President. He should be a happy man. He shouldn’t be upset when his Neo-Nazi nature is described accurately.

You’re free to waste your money supporting observable lies.

After all, think of the $1.2 billion Crooked Hillary wasted on her campaign, many of it extracted from mindless rubes like yourself. I read your pathetic screeds insulting the wonderful John C Wright on the subject.

Well, I’m honored to have you as a reader, Slayer

Slayer of Bottoms? That’s…not at all suggestive.

Not my username or the reference. And I’m shocked, absolutely shocked, that you would be fixated on male ass, especially where it doesn’t appear.

Male ass? You were the one that brought that up, dude.

Stay strong, BottomSlayer.

A wonderful example of the second rule of SJWs; when caught claiming something wrong, in this case insisting that “Bodom” is really “Bottom”, the SJW doubles down.

Whether this is due to dishonesty, idiocy, or an unhealthy fixation on male posteriors is an open question.

Overly pedantic and stilted writing style? Check. Strict adherence to his Dark Lord’s writings? Check. Gay panic when forced to confront the fact that he’s the one who brought up dude booty? Check.

You’re well on your way to VFM status, BottomSlayer! Has VD assigned you a number yet?

SJW? Meh. I just hate Nazis.

It’s truly breath-taking that you continue to lie and double and triple-down when anyone can simply scroll up and read who first brought up “bottoms”.

It’s even funnier that you think you’ve provoked “gay panic”, as opposed to mockery of you being a juvenile idiot with an infantile fixation on male ass.

I read Vox’s blog (some of which I disagree with), but I’ve never been a VFM.

I hate Nazis, too. They were socialists who hated Jews and loved the “Mohammadean faith”.

Ergo why I hate SJWs, who share those three characteristics.

Russian Jews aren’t white? You lied to me, Jessica and Alex! Lied with your appearance!

Most white nationalists, let alone any white supremacist, would make a severe distinction between Europeans who are white versus those that are Jewish.

But you are fooling yourself if you think the only people that support white nationalism are “white supremacists”, “neo-Nazis”, or necessarily even “white”.

Most white nationalists and their supporters are idiots and I don’t know why I should acknowledge their opinion of whether or not Jews are white with anything but dismissal.

One thing the Neofascist alt-Right does extremely well is spend endless amounts of time shutting people – especially female people – up on the internet. Shame, shame and shame on anyone who plays their game. This is a very important article.

Wow. Just wow.