Websites, newspapers and broadcasters had a lot of fun last October 21 – the date by which, according to Back to the Future Part II, the world might have flying cars, self-lacing shoes and Jaws 19.

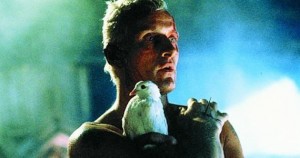

Of slightly more esoteric interest was January 8 this year, which was the birth (or “incept”) date of Roy Batty, the rebel replicant, or robot, from Blade Runner.

Batty, you’ll remember, was, by 2019, a desperate and angry replicant, determined to find the creator who seemed so indifferent to his existence and his cruelly limited life span. (Welcome to that club, robot.)

Science fiction movies set in the relatively near future tend to court some valuable interest at the time of their release, at the expense of inviting derision when that future date arrives.

Blade Runner imagined an Earth where the atmosphere had been ruined and the affluent had mostly left the planet. It also, to the delight of many observers, speculated that the brand names of Atari and Pan-Am would be highly visible in the 21st century. 2001: A Space Odyssey similarly foregrounded the Pan-Am name, but it also took a pretty serious stab at anticipating what technology might look like when the new millennium arrived.

Many commentators like to check off the things that SF movies and television got “right” and “wrong” about the near future, but I think that does the genre an injustice.

I’m focusing on films here, because similar discussion of SF literature hardly ever reaches mainstream forums. The only novel I can remember being widely talked about in the same way is Nineteen Eighty-Four, which prompted endless discussion in late 1983 about whether Orwell’s visions had “come true”.

Inevitably, almost everything “predicted” in movies set in the near future doesn’t happen.

Things To Come in 1936 is a rare example of a film that came pretty close on some points, depicting a Second World War starting at Christmas 1940. That was probably not a very wild guess in 1936, although the film also predicted the war lasting until the 1970s, when an organisation called Wings Over the World would come out of Iraq to rescue the remains of civilisation.

But 1972 came and went without the US attempting the first interstellar flight as in Planet of the Apes. NASA did not launch “the last of America’s deep space probes” in May 1987, as per TV’s Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, and a nuclear war did not start that November 22, as that series imagined, or on any of the other dates referred to in SF.

Manhattan was not turned into a high security prison in time for Air Force One to crash land there in 1997 as in Escape From New York. And there was no explosion of nuclear waste to send our moon hurtling through space with a human colony on it in 1999, as seen on television in Space: 1999.

A couple of the works mentioned above are pretty weak, but not because of their inability to read the future. It’s amusing, and sometimes enlightening, to compare the world envisaged in such stories with the real world as it turned out, but we shouldn’t make too much of it.

In some cases, the authors of such stories chose a date in the near future as an easy way of engaging our interest, on the basis that “this could all happen very soon”. In other instances, such as 2001 and Blade Runner, the authors were seriously imagining the kind of world that might result if certain trends continued. It’s speculative fiction, not predictive fiction, and it tells us something about the eras in which these works were conceived.

Prediction of anything important is almost impossible. After all, hardly anyone predicted the near-collapse of the world’s financial system in 2008, despite quite a few people being well paid to watch for signs of exactly that.

George Lucas opted out of all this “Could it really happen?” discussion by setting Star Wars “a long time ago”. Others have escaped it by setting their stories in the far-flung future, when none of us will be around to quibble the accuracy of their visions, unless we are catapulted centuries into the future like Charlton Heston’s Taylor or Captain William ‘Buck’ Rogers.

But those who are brave enough to set their stories in the near future should see them discussed in more interesting terms than just “Did it come true?” In the end, the key thing these creators may really have failed to predict was that we would still be interested in their work decades later.