Images have power. Nothing has shown that more clearly than the sudden turn of the tide in the current refugee crisis, after the image of the little boy found drowned on a Turkish holiday beach made the rounds of the social networks and the media.

To be sure, for many people it must have been the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. The outpouring of sympathy and practical help we’ve been witnessing this last week, particularly in Germany and Austria, but also, finally, in the UK where several grassroots initiatives have sprung up to provide for the people stuck in Calais, has made one thing clear: the politicians who believe they pander to popular feeling when they talk about building fences and turning back boats, the media people who try to sell their stories by stoking up dark age fears of wild hungry hordes besieging Europe, are utterly out of touch with how their readership, how the population they are supposed to represent, actually feels. People want to help. They really, really do.

Speaking for myself, I have been low level aware of the situation for quite a long time – many years, in fact. I’ve been taking in the news of people stuck in refugee camps for indefinite periods, of people drowning in droves in the Mediterranean, or slowly dying on boats unable to land anywhere, while the media called them “hordes” and “swarms” and even, apparently, “cockroaches”, while governments spent their money building fences and detention camps instead of providing help, with a growing sense of dismay and frustration.

Was Europe, and the rest of the western world, so far gone to the far right these days, that we think we have the right to divide the world into those who may live (and in prosperity, at that) – and those whose lives are not valuable enough? How could it be that politicians could hope they would not have to deal with the problem if they simply did nothing, and let people drown? How is that better than putting them in a gas chamber right away?

Isn’t our sense of moral superiority based precisely on the fact that we have created documents like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights? Had people forgotten that this document explicitly states that refugees have rights? We’re not talking charity here: we’re talking legal obligation.

If I’ve been holding those news at arm’s length so far, it is because they hit a little too close to home: I come from a family of refugees myself.

To me, these are not abstract items on the news. They are my mother’s nightmares, and her ongoing panic attacks. Her childhood ended very abruptly one day when she was eight years old, and her mother put her and her sister on a train to join family in what is now the Czech Republic, to keep them safe. She is pushing eighty now.

A couple of months later the war had caught up with them, and my grandmother bundled up her two girls and whatever belongings she could fit on her trusty bike. They became part of the flood of ethnic German refugees from Eastern Europe who made their way, largely on foot, to reach a Germany in ruins.

The numbers? Circa 14 million, of which about 2 million lost their lives due to allied bombings, murder by the advancing Russian troups, or to deprivation. And those were just the ethnic Germans: other nationalities such as Poles, Ukrainians, and Baltic people, as well as the Eastern European Jews, were also displaced en masse due to Stalin’s “russification” policies and ongoing antisemitism after the war.

Somehow, they got taken in and provided for, just barely: there wasn’t nearly enough food those first couple of years after the war, and my mother tells stories of foraging for edible weeds among the railway tracks, of cooking the potato peels more fortunate people had thrown away. Of being permanently cold and hungry. They were allocated a room that had a hole in the floor from bomb damage. But somehow they pulled through. My grandma worked as a Trümmerfrau – the women who cleared up the rubble of bombed buildings, very physically demanding work but it entitled her to more food coupons to feed her daughters.

Ten years later, Germany was back on its feet and experiencing one of the greatest economic booms in history — while my hardworking grandmother was unemployed for three years. She died before I was born, of lung cancer brought on by inhaling the asbestos from the bombed buildings she had helped clear up. She was by all accounts an unusually clever, brave, and very resourceful woman. I would have liked to have met her.

If Europe could manage it in 1945, when it was in smithereens and licking its wounds from the war, what’s the excuse for not managing it now?

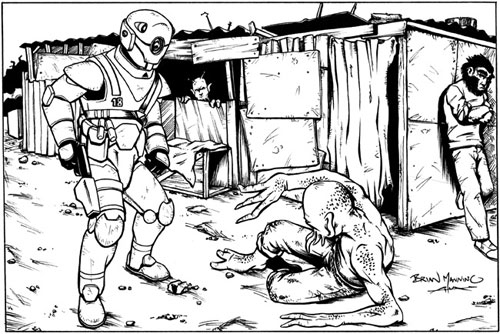

This is an art blog, and I have tried to find art that would fit the topic. It has been an extremely disappointing quest. Refugees clearly are “them”, not “us”. The unease artists feel with this topic is palpable. There are images of men and women in various tormented poses, there is an abundance of photographs of cute children with haunted eyes, there is games art showing all manner of squalor and greedy desperation. Apparently there are video games where the gamer can gain points by killing off refugees – like, well, cockroaches. It is not the kind of art I want to give a forum on this blog.

I have picked a small selection of images which approach the topic from a more unusual angle: the alien and the fairy tale creature, stuck in a hostile world. A historical painting which points out the fact that the problem is by no means new. Photographs of an Afghan refugee spending the night at a bus stop holding a baby on his lap, and of a makeshift settlement in Syria. Images that don’t subscribe either to sensationalism or to cutification – both attitudes of people looking on from the outside – but capture some aspect of the actual experience of being a refugee.

But to me, the most powerful images are the historical photographs I culled from the internet last week to post on my Facebook account: those are the stories my mother tells me. I would like to share them here, even if it is somewhat off topic for this blog.

Images are copyright the respective artists and photographers and may not be reproduced without their permission. This does not include the historical photographs of the post-WWII refugee crisis.

1 Comment