When I was in undergrad, there was a lot of talk about the study of social history replacing political history as the primary means of teaching history. Now it looks like counterfactual history is gaining in popularity, but not everyone is happy with this trend, including noted British historian Richard J. Evans. In his recent article published by The Guardian, he slams counterfactual history as being a “misguided and outdated” method of understanding history.

When I was in undergrad, there was a lot of talk about the study of social history replacing political history as the primary means of teaching history. Now it looks like counterfactual history is gaining in popularity, but not everyone is happy with this trend, including noted British historian Richard J. Evans. In his recent article published by The Guardian, he slams counterfactual history as being a “misguided and outdated” method of understanding history.

(I highly recommend you read the article, or else what I have to say might not make much sense.)

Long-time readers probably don’t need to be reminded that I am a big fan of alternate history. So seeing that article touched off many of my nerd rage buttons, although truth be told, I don’t think Evans was taking potshots at me personally. Alternate history and counterfactual history are certainly related, but they differ on their focus. Alternate history is used by writers to craft fictional settings for their stories, while counterfactual history is used by serious scholars to study history. There is no denying, however, that there is a lot of crossover between the two genres and the term “counterfactual” is often use interchangeably with alternate history, especially in Britain.

So I though a response from me was warranted, even if Evans is unlikely to read it. I have to admit Evans made some good points in his article. Many counterfactuals are poorly done both in the scholarly and speculative worlds. They are often products of the author’s wishful thinking (i.e. the world would be a better place if my guy won) and thus replace solid historical research with the author’s own bias. The over reliance on the Great Man theory of history is a common problem and Evans’ is right in stating that there is no guarantee that had Archduke Franz Ferdinand survived Sarajevo, war would have been avoided. The outcome of specific battles (the Battle of Gettysburg is a big offender in this regard) also hurts the plausibility of timelines because the author narrowly views history instead of paying attention to the larger forces at work (i.e. economic and social factors).

Yet Evans contradicts himself in his own article. He states that counterfactuals are not useful tools for historical research because they can’t be disproved. Nevertheless, he specifically brings up the counterfactuals proposed by historians Niall Ferguson and Max Hastings (specifically the aftermath of a German victory in World War I) and points out the flaws in their arguments, despite the fact he said counterfactuals can’t be disproved. You get the idea from reading the article that Evans does not like these men or their politics, thus allowing his own bias to warp his view on counterfactuals in general. Evans appears to have the making of a great counterfactual historian, if he could just get over his distaste of the genre.

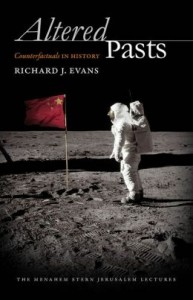

Although I am sure Evans has more examples in his book, Altered Pasts: Counterfactuals in History, he ignores other scholars who have avoided common mistakes made by counterfactual historians. Roger L. Ransom‘s The Confederate States of America: What Might Have Been focused primarily on economic factors as he speculated on an independent Confederacy. Frank P. Harvey’s Explaining the Iraq War: Counterfactual Theory, Logic and Evidence, meanwhile, uses counterfactual history to disprove the Great Man theory by pointing out that had Al Gore won the US Presidential Election in 2000, the United States would still likely be involved in a war with Iraq. These are just a few examples of counterfactuals that take into account the great, impersonal forces at work in our history.

Although I am sure Evans has more examples in his book, Altered Pasts: Counterfactuals in History, he ignores other scholars who have avoided common mistakes made by counterfactual historians. Roger L. Ransom‘s The Confederate States of America: What Might Have Been focused primarily on economic factors as he speculated on an independent Confederacy. Frank P. Harvey’s Explaining the Iraq War: Counterfactual Theory, Logic and Evidence, meanwhile, uses counterfactual history to disprove the Great Man theory by pointing out that had Al Gore won the US Presidential Election in 2000, the United States would still likely be involved in a war with Iraq. These are just a few examples of counterfactuals that take into account the great, impersonal forces at work in our history.

Counterfactuals are also a useful teaching tool in the classroom. For a subject slightly more popular than math, the way history is taught in the modern classroom is often criticized for portraying a biased and distorted view of history that spends too much time on “great men.” Counterfactuals can be used instead as an imaginative way to teach cause and effect in history by showing students that events in one nation or their own can have a direct effect elsewhere (i.e. the debt cause by France’s intervention in the American Revolution was a direct cause of the French Revolution) and that a single individual is unlikely to have as great impact on history as the old books would make you believe. As globalization continues, it is important for future leaders to understand this as we all try to ride safely on the waves of history.

Turning to the fictional side of counterfactuals, alternate history is also an important tool in understanding history. Just as television shows like Star Trek inspired future scientists and engineers, so too can alternate history inspire people to learn more about actual history. If these works tend to focus primarily on the altered actions of a single individual or the different outcome of one battle, they can be forgiven because fiction is meant to tell a story and stories are about people, not impersonal forces. People want to read or watch interesting people solve difficult dilemmas or fight in epic battles. Just because they may not be realistic or present a incomplete picture does not mean they should be thrown out. How many works of speculative fiction would be thrown out just because they didn’t follow the laws of physics? They should instead be recognized as gateways to further learning by those future scholars who pick them up.

There are pros and cons to counterfactual history, just as their are pros and cons to social, economic, political and military history. While many of Evans’ points are valid, he ignores good counterfactual history because he can’t see past the poor counterfactuals is he rallying against. While I am certainly biased myself when it comes to counterfactuals, I don’t feel they are hurting our understanding of the past anymore then other trends to historical research have done. I respect Evans’ opinion and do look forward to reading his book as I find learning about a contrary opinion to your world view is a healthy exercise for the mind, but I am not convinced that counterfactuals are a waste of time.