If you’ve been a collector (or dealer) for a long time, it’s easy to get cynical about the stuff you buy and sell. Especially when artists, or other collectors, tell you “It’s not for sale.” Really? Isn’t everything for sale, “at a price“? Sometimes yes, and sometimes no. It took us years to figure that out.

Collectors will look you straight in the eye and declare “over my dead body” and a few months later you see it online, on some popular site like www.comicartfans.com, and oh no! it’s in the collection of “X” 🙂 So sometimes a “no” ends up being no, but sometimes not! It depends, right?But depends on what??? Telling the difference between those times when “no” is really a no and those times when the right offer by the right person at the right time in the right place to the right owner can result in “prying it loose” can be hard, even for seasoned collectors.

Artists are just as guilty of this as collectors. They will tell you flat out “it’s not for sale” (the dreaded “NFS” on the bid sheet at conventions!!) and the next time you see them, guess what? It’s been sold. And all too often, and incredibly frustrating for you, at a price LOWER than you would have been willing to pay. Or that you even offered—before they said NFS.

You’ll Never Know Unless You Ask . . . right?

Right. And if the answer to the question “Is that one for sale?” is “yes” then (per standard practice and tradition) the person doing the selling is responsible for setting a price. Because Things For Sale are expected to have prices attached to them.

This holds true whether you are buying shoes, tomatoes, or art. If the owner of the goods has no idea what they’re worth . . . then it behooves them to do a little research, or whatever it takes, in order to come up with a price. If you find yourself in a situation where you have something to sell and know nothing about WHAT it is you are selling, well . . . there is a cure for that. It’s called EDUCATION. And if you find yourself in a situation where someone else has something to sell, but is unwilling, or unable, to set a price on it, then I say WATCH OUT. It’s a negotiation that is bound to go badly.

But what if you ask, and the answer to that question is not “yes” but “no”? What do you do with that? What does that mean? Well, for one thing, it means you have either asked the wrong question, or (more accurately) asked the right question in the wrong way. 🙂

For starters, and unlike PRICED objects, you can assume that anything that does NOT have a price attached to it, MAY or MAY NOT be for sale. Put another way: If it turns out to be available, the price is not fixed and/or is not going to be sold without negotiation. If it’s a person sitting behind a stack of shoes or tomatoes, or a piece of furniture in an antique shop, then the proper question is something on the order of “What do you need for those?” or “What are you asking for those?” This provides the flexibility and leeway the seller is looking for, because they are NOT COMMITTED TO THEIR PRICE. You know they want to sell, and they know you are interested in buying, but the price is negotiable. You will know when you are in the same situation (“May be for sale”) even when the answer is “No” when it is quickly followed by “but. . . could be,” or some variety of the well-worn “make me an offer that I can’t refuse.”

Then what? Then (per standard practice and tradition) the person doing the buying is expected to make an offer. This holds true whether you are buying shoes, tomatoes, or art. If the person wanting to buy has no idea what to offer . . . then it behooves them to do a little research ahead of time, or whatever it takes, in order to be ready with an offer, should the occasion arise. If you find yourself in a situation where you want to buy something and don’t know the market value of WHAT it is that you want to buy, well . . . there is a cure for that. It’s called EDUCATION. But BE CAREFUL. Don’t make offers frivolously, lest the seller accept! And if the response is not a counter-offer, but rather a “let me think about it” be sure to set a time limit on your offer. You don’t want to be an unwitting participant in a fishing expedition or private auction.

Motivations and Psychology

Timing, incentive, emotions . . . all of these play an important role in acquiring and parting with collectibles. Original Artwork is not your ordinary shoe, tomato, or even antique 🙂 Sometimes objects are for sale, but just not “now.” Or “here.” Or “to you.” Or at the price you’re willing to pay. Or even for money! (For example, some things you can acquire only through ‘trade.’) Just like a good salesperson prepares for “meeting objections” from reluctant buyers, a person wanting to purchase art that is, technically, “not for sale” must have a good grasp of human behavior—and prepare for the responses of reluctant sellers.

Ask the artist who has “NFS” next to the artwork, “what does that really mean?” We found out, over the years, that many times all that meant was “I want to keep showing this work in public for a while, because it’s one of my best” or “I can’t decide what to ask for it” or “I haven’t taken a good photo/scan/transparency of that one yet, and I can’t sell it until I do.” Overcome those challenges to selling, and the work can be yours!

Ask the owner of the art who says “no,” “why not?” What is the real reason preventing them from selling? Sometimes how payment is made, makes all the difference (cash, not check; check not payment plan) Sometimes it’s really just a matter of how high you are willing to go. Because at SOME point, whatever that point is, only a fool would not sell. RIGHT? WRONG.

When Art is Really Not for Sale

There really are situations where the owner’s emotional attachment to the art will override any buyer’s desire to own it. Where the gap between what a buyer is able to pay (however reasonable, or however much), and what a seller considers “enough,” given the actual street value of the art, is so wide that no offer is going to be persuasive.

This is one of the most common ways that art gets to be “really not for sale.” And this especially applies to art that is modestly priced to begin with—but which (later) turns out to have special meaning or attraction to those who own it, and those who desire to own it.

Turning down offers that are double, triple, or more than the owner paid seems totally nonsensical, and illogical. But eventual profit taking is probably among the least important aspects of collecting, for us. We’re not in it for the money. And I’m sure that other collectors feel the same way.

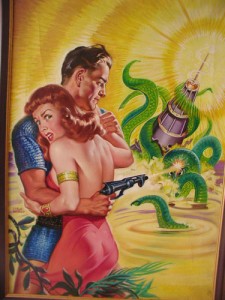

The artworks I’ve shown in this posting are examples of what I mean and are all pieces in our collection. There are stories behind each of them. The Bergey was our “first baby,” the very first painting in the SF genre that we ever bought. We bought it from (the late) Gerry de la Ree, circa 1975, for $75.00. Which was very kind of Gerry, because at the time we knew a fair price for the painting should actually have been about $150. It doesn’t matter that we could probably sell it for at least $35,000 today. It’s not for sale.

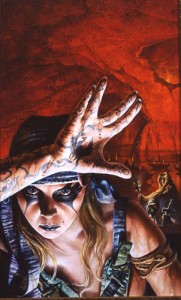

The Ruddell I originally sold (as the artist’s agent, via Worlds of Wonder) to a fellow collector, Richard Kelly, in the mid-1990s. I didn’t want people to think I was “cherry picking” art before I offered it, so I grudgingly sold it, even though I loved it. When Kelly changed his collecting focus to American illustrators, and began liquidating his genre art post-1937, I bought it back at the same price he paid for it, in 2000. I’ve had offers to sell it, since then. But I don’t make the same mistake twice. 🙂 It can’t be replaced for what it’s worth, so what’s the point? It’s not for sale.

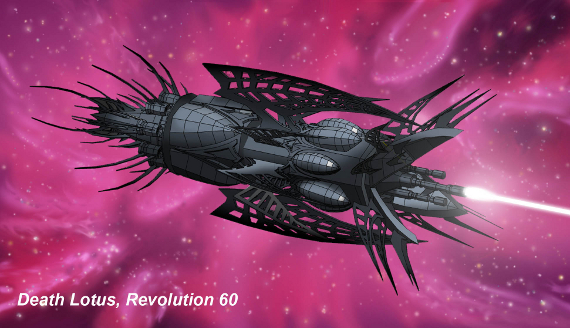

The Stanley we paid too much for to begin with, and we knew we were over-paying for it, even while writing the check. 🙂 The day may come when we will decide to sell it. Meanwhile, we don’t need to accept any offers that are “fair”, even if that would mean we’d break even, plus a little. We don’t need to prove a point, we don’t need the money. So, it’s not for sale.

I daresay many of you have stories on this subject, or own works that you would not part with, either. If you’d like to share those works and reasons with me, I would be happy to create a “part 2” on this topic!

Recent Comments