Photo by Shawn McConnell

Today we are joined by award-winning author, editor, and critic Gary K. Wolfe. Gary writes science fiction book reviews for Locus Magazine. After more than twenty years of writing reviews, he has placed himself on the top shelf of historic science fiction critics alongside such legends as Damon Knight and James Blish. His deep insight into the nature of literature and his intimate knowledge of science fiction history allow Gary to tug at the strings that weave the genre together. The collection of books he has published reveals a fabric that stretches across the entire breadth of fantastic literature, while highlighting the genius of a few giants within the industry.

Gary is Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University’s Evelyn T. Stone College of Professional Studies, where he works on expanding young minds. Digging through the stacks of books in his office, you may run across one of his many awards. Gary has been awarded the Pilgrim Award, the Distinguished Scholarship Award, the Eaton Award, a British Science Fiction Association Award, a World Fantasy Award, and a Locus Award. When not rappelling down the mountain of unread books in his home, Gary works on developing an awareness replicator that will allow him to read fifty novels at once.

R. K. TROUGHTON FOR AMAZING STORIES: Welcome to Amazing Stories, Gary. You began your tenure at Locus Magazine in 1992, when you published your first science fiction book review. During that time, you have reviewed well over two hundred novels and have published countless essays. Please tell us how you got started with Locus Magazine and what keeps you going back for more.

GARY K. WOLFE: I had actually been writing reviews for more than a decade before Charles invited me to join Locus, first in various scholarly journals about SF and then in a magazine called Fantasy Review. That was where I started to review more fiction, and I think that’s where Charles saw the reviews that led him to invite me aboard.

I keep an index of the Locus reviews, and I’ve actually written 265 columns as of this month, which adds up to more than 1300 books reviewed. Why do I keep going back? I think when you start as a reviewer, you’re just thrilled to get the free books and to get paid for what you write. That wears off pretty quickly, but by then, if you’re lucky, you realize people are actually reading the reviews, and then you’re part of what Charles called the “great conversation” about science fiction that’s been going on for many decades. And while it’s easy to get annoyed at how repetitive and formulaic SF and fantasy can be, they’re also capable of showing you something completely new with surprising regularity.

ASM: What was it like working with the legendary Charles N. Brown?

GKW: I suspect almost anyone you’d ask would have the same answer: enormously rewarding and totally maddening. Charles was strongly opinionated and had such an encyclopedic knowledge of SF that at first it was hard to argue with him. But I eventually realized that you could win some arguments with him, and it seemed a great compliment when he’d occasionally tell me that a review I’d written had caused him to change his opinion about a book or a writer. For someone who was as passionate about classic SF as anyone I’ve met, he also had surprisingly eclectic tastes. He loved historical fiction, good mysteries, and sea stories, and late in his life developed a deep appreciation for genre-bending writers as diverse as Graham Joyce or Kelly Link. So he was not as fusty a member of the Old Guard as many people think.

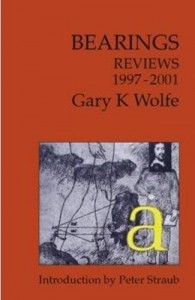

ASM: You have published three collections of reviews that you call Soundings: Reviews 1992-1996, Bearings: Reviews 1997-2001, and Sightings: Reviews 2002-2006. Please explain the distinction between each grouping and what readers can expect to find inside.

ASM: You have published three collections of reviews that you call Soundings: Reviews 1992-1996, Bearings: Reviews 1997-2001, and Sightings: Reviews 2002-2006. Please explain the distinction between each grouping and what readers can expect to find inside.

GKW: People had been asking me to collect reviews for some time, and when Roger Robinson of Beccon Press—which had published collections of my good friend John Clute—invited me to put a volume together, it turned out to be harder than I’d expected. At first I’d planned to do a smaller selection organized maybe by themes or authors, but John encouraged me to simply arrange them chronologically, to create a kind of chronicle of the last couple of decades. And since Roger was willing to do multiple volumes, I ended up including most of what I’d written for Locus during those 14 years—although there are quite a few reviews omitted, mostly of nonfiction titles or annual anthologies. Of course, I also missed reviewing some major titles during this period, and I regret that they aren’t covered in the collections.

ASM: How have you developed as a critic from your first review to the one you are writing this month?

GKW: That’s a good question, but I’m not sure I’m the best one to answer it. Of course those early thrills I mentioned are long gone—I get a lot more books than I can possibly review—but I think I have a better sense of what reviews can and cannot do, and of who the Locus readers are. I’ve been doing a few reviews for the Chicago Tribune the last few months, and it’s interesting how you need to approach a book differently for a general audience than an SF audience, and which books you choose to review.

I used to want to review big names and big titles, but these days I think the most important thing a reviewer can do is to call attention to a good book that readers might overlook because it comes from a small press or doesn’t get much publicity or is by an author they’ve never heard of.

ASM: Your collection of essays Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature earned you the 2012 Locus Award for nonfiction. For those who have not read the book, tell us what we can expect to find when we pick up a copy.

ASM: Your collection of essays Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature earned you the 2012 Locus Award for nonfiction. For those who have not read the book, tell us what we can expect to find when we pick up a copy.

GKW: Since the beginning, I’ve had a kind of dual career in SF—the reviews on the one hand, and academic books and essays on the other. Evaporating Genres is a collection of academic essays written over many years, with the old ones updated and corrected a bit, but all reflecting the idea that genres are changing and blending into each other in various ways. Of course, a lot of the book is about SF, but there’s also stuff about fantasy, horror, and historical fiction, and even about SF criticism.

ASM: Many readers who are new to science fiction are not familiar with the classic novels of the Golden Age. Last year you published the book American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s, and you helped create the companion website. The list of amazing novels written in the 1950s is staggering. Your collection includes such great authors as Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth, Theodore Sturgeon, Leigh Brackett, Richard Matheson, Robert A. Heinlein, Alfred Bester, James Blish, Algis Budrys, and Fritz Leiber. With so many great novels to choose from, how did you settle on these nine?

GKW: I’m actually surprised that I haven’t been asked this more often. There were a lot of considerations in arriving at those novels. One is simply length—the Library of America wanted to get four or five novels in each volume, which made it hard to look at very long novels. Another rule, which I made up myself, is that the novels should be actual novels of the 1950s, and not fix-ups of 1940s stories, which eliminated a lot of classic books. I wanted to make the argument that the modern SF novel was essentially an invention of the 1950s, if only because that was the first time there was a major commercial market for it. That’s part of what I argue on the website, with crucial support from Barry Malzberg and Robert Silverberg. Finally, there was an effort to reflect the 50s as a period, so we included a Cold War novel (Budrys) and a novel reflecting nuclear anxiety (Brackett). I also wanted to get a sense of the variety of 50s SF novels, so we have a satirical classic (Pohl & Kornbluth), a Heinlein classic, a kind of proto-cyberpunk novel (Bester), a treatment of religion (Blish), etc.

GKW: I’m actually surprised that I haven’t been asked this more often. There were a lot of considerations in arriving at those novels. One is simply length—the Library of America wanted to get four or five novels in each volume, which made it hard to look at very long novels. Another rule, which I made up myself, is that the novels should be actual novels of the 1950s, and not fix-ups of 1940s stories, which eliminated a lot of classic books. I wanted to make the argument that the modern SF novel was essentially an invention of the 1950s, if only because that was the first time there was a major commercial market for it. That’s part of what I argue on the website, with crucial support from Barry Malzberg and Robert Silverberg. Finally, there was an effort to reflect the 50s as a period, so we included a Cold War novel (Budrys) and a novel reflecting nuclear anxiety (Brackett). I also wanted to get a sense of the variety of 50s SF novels, so we have a satirical classic (Pohl & Kornbluth), a Heinlein classic, a kind of proto-cyberpunk novel (Bester), a treatment of religion (Blish), etc.

ASM: My personal journey into science fiction is forever shaped by the stories of Harlan Ellison. In my mind, he stands at the summit of the genre. Along with your late wife Ellen R. Weil, you wrote a critical study of Ellison in the book Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever. Many consider the book to be essential reading for any fan of Ellison or student of the genre. Please tell us about the creation of this book and how your understanding of Harlan Ellison changed during the writing.

GKW: We had the obvious misgivings about writing a book about an author who was already a friend before we began, but Harlan and others encouraged it, and there had been remarkably little critical work about him. The main thing we learned was his versatility—everyone knew about the SF, but the pulp crime stories, the TV and movie scripts and criticism, the “juvenile delinquent” stories and books, and the mainstream stories were a revelation—he was a broadly ambitious writer who just happened to find his greatest success in SF. With something like 1200 stories to read, there were obviously a lot of clunkers, and I think Harlan was initially disappointed in our pointing this out. But we’ve talked several times since, and he seems to understand what we were doing and why. His classic works still hold up as SF classics, and there are a number of brilliant stories that aren’t as widely read.

ASM: Many science fiction fans can point to a single book, movie, or television show that sparked their interest in the genre. What hooked you on science fiction, and how old were you?

ASM: Many science fiction fans can point to a single book, movie, or television show that sparked their interest in the genre. What hooked you on science fiction, and how old were you?

GKW: I’m not sure why I started picking up SF in the local public library when I was 8 or 10, but two titles I remember were Andre Norton’s Star Man’s Son and a novel called Star Ship on Saddle Mountain, by an author with the unlikely but apparently real name Atlantis Hallam, who wrote only a handful of minor SF stories besides the novel. When I started buying paperbacks with my allowance, the first one I remember paying for was Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man, so I really started out as a rather heavy Bradbury fan. His was the first name I knew to look for, and Ballantine was the first publisher I came to feel I could depend on. Sturgeon and Clarke followed, and I came a little late to Heinlein and Asimov.

ASM: Your depth of reading goes beyond fantastic fiction into other genres and literary classics. Which authors have most influenced your tastes while setting the bar for everyone else you read?

GKW: I don’t think you can set the same bar for every author, since authors set out to do different things. But I suppose if someone sets out to do hardboiled noir with a distinct sense of place, I’ll be at least unconsciously wondering how well they stand up to Raymond Chandler, and if someone goes for a kind of mystical psychological realism, I’ll wonder how they hold up to Flannery O’Connor. Macho writers who like short sentences have Hemingway to contend with, while regional writers who want to imbue their settings with a sense of deep time have Faulkner to deal with. For a well-crafted short story that can reveal a great deal through subtle character interactions, I suppose my model is Katherine Mansfield. What does surprise me is that some SF or fantasy writers have been able to take on these challenges, and meet them honorably.

ASM: Many consider you, along with your one-time mentor James Gunn, to be one of the foremost historians of science fiction. Science fiction has had notable periods such as the Golden Age and the New Wave. If you had to label or categorize the current era of science fiction, how would you describe it?

ASM: Many consider you, along with your one-time mentor James Gunn, to be one of the foremost historians of science fiction. Science fiction has had notable periods such as the Golden Age and the New Wave. If you had to label or categorize the current era of science fiction, how would you describe it?

GKW: I wouldn’t begin to claim to be an SF historian in the sense of James Gunn or Brian Aldiss or others, but a word that comes to mind for the current era is “diaspora.” I like it for a couple of reasons. For one thing, SF is spreading out to other areas—time travel shows up in bestsellers by Lauren Beukes or Audrey Niffenegger, while writers as varied as Margaret Atwood and Michael Chabon write novels that are clearly SF. The other meaning of diaspora is that SF seems to be opening up to other cultures—we’re seeing SF from Africa, China, Japan, the Caribbean, India, the Middle East, and of course Europe. I think SF has been an international literature for a long time—think of Verne, or Metropolis—but we’re starting to see more of it in the US, and I hope it’s energizing the whole field.

ASM: Part of your insight when reading a book comes from your ability to free your mind from the boundaries of genres and sub-genres to judge each book on its own merits. Please describe to us your approach when evaluating a book and what elements you believe make up the anatomy of a good novel.

GKW: I really don’t have any rules for what makes a good novel, because I’ve discovered that as soon as I think of some, I read a novel that violates them all and is still terrific. What I try to do is figure out what the author is trying to do, and then read the novel in that spirit. If someone just wants to write an old-fashioned slam-bang space opera, you read it in that spirit and don’t expect a lot of psychological depth or Faulknerian prose. But if the author is trying to write a space opera with a lot of psychological depth and complexity, you go with that and see if they’ve succeeded. You often seen writers who are actually better than the material they’re working with, and occasionally authors who are not quite up to their ambitions, but you have to go with what their apparent intentions are—which, I might point out, are not necessarily the same things that the marketing people are trying to promote.

ASM: You seem to share my lack of patience for bad fiction. While many readers will plow ahead until they reach the last page or tell me it gets good after one hundred pages, I find myself discarding the book in favor of something that grabs me from the start. What are some of the biggest mistakes that authors make that cause you to move on to the next book in your endless stack?

GKW: Locus in general has sometimes been accused of writing only positive reviews (though I could give you from personal experience the names of a lot of authors who don’t think that), but in fact the editors—first Charles, and now Liza—leave it up to the reviewers as to what they actually end up reviewing. This means, for me at least, that I don’t review a book unless it’s interesting enough to finish. There are lots of ways a book can pull you through it—an interesting plot, a fascinating setting, or just gorgeous prose—but there is always the question of whether this book is more interesting or important than the next one in the stack. I suppose one of the things I keep an eye out for is whether the author shows a decent respect for the reader, neither pandering to expectations (in which case you often know where the book is going by the end of the second chapter) nor trying to show so many pyrotechnics that the reader feels condescended to or manipulated. Just tell an honest story.

GKW: Locus in general has sometimes been accused of writing only positive reviews (though I could give you from personal experience the names of a lot of authors who don’t think that), but in fact the editors—first Charles, and now Liza—leave it up to the reviewers as to what they actually end up reviewing. This means, for me at least, that I don’t review a book unless it’s interesting enough to finish. There are lots of ways a book can pull you through it—an interesting plot, a fascinating setting, or just gorgeous prose—but there is always the question of whether this book is more interesting or important than the next one in the stack. I suppose one of the things I keep an eye out for is whether the author shows a decent respect for the reader, neither pandering to expectations (in which case you often know where the book is going by the end of the second chapter) nor trying to show so many pyrotechnics that the reader feels condescended to or manipulated. Just tell an honest story.

ASM: At this point in your career as a critic for Locus, the free books keep crawling into your home like an army of ants after a long rain. Since 1992, how many ARCs (Advanced Reading Copies) would you estimate you’ve received?

GKW: I have no idea, and it would be depressing to try to tot them all up. Liza Groen Trombi, the editor of Locus, and Jonathan Strahan, the reviews editor, know my interests well enough that ARCs which arrive from the magazine are usually interesting, but I also get a lot from publishers or even authors who often seem to have no sense of what I’m likely to review, or what Locus is likely to review.

ASM: Since you completed your honors thesis at the University of Kansas in 1968, how have science fiction and the publishing industry changed?

ASM: Since you completed your honors thesis at the University of Kansas in 1968, how have science fiction and the publishing industry changed?

GKW: I’m surprised that you tracked down that honors thesis, which I did for Jim Gunn on Bradbury. But this is a long period to cover, so I can only give impressions. I do think that around 1968 SF began a process of diversification which in various ways has been going on since. You had the New Wave, the Dangerous Visions anthologies, the growth of feminist SF, the rise of a new generation of more experimental writers, and the sort of boys’ club that had dominated SF since the beginning began to lose its hold. It’s also when SF started going mainstream with films like 2001 and writers like Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein showing up on national bestseller lists.

Today, only a handful of writers can do that—George R.R. Martin, Neil Gaiman, Orson Scott Card—and the days when a fan could pretty much read everything faded away. The publishing industry seemed to fall more and more into the hands of accountants, and SF became more and more of a smallish niche; today even major writers have to turn to small presses to do short story collections. But from a literary point of view, you no longer get laughed at when you claim that the best SF holds up to the best literary fiction, or that literary fiction increasingly borrows SF tropes. SF may have lost a lot of its clubbiness, but from a literary point of view it’s as good as it’s ever been.

ASM: The foundation of science fiction is fandom. Some might suggest that over the years fans have indirectly influenced the path science fiction has taken. How do you see this relationship between fans, authors, and the publishing industry?

GKW: A good question, and one that’s often overlooked in historical discussions of SF. From my own perspective as a critic and scholar, the only real models I had starting out were critical essays and reviews published in fanzines or even pulps—those by Damon Knight, James Blish, Algis Budrys, Joanna Russ, and of course Jim Gunn. Most of the major early bibliographies and reference works of SF and fantasy came from fans—academics back then just weren’t very interested—and even though most of that sort of thing has migrated to the Web, it’s still a crucial resource. Many of the important early publishers were essentially fan presses, and the whole con culture is still the work of fans. So there’s no doubt of the importance of fans to the whole social structure of SF, but at the same time certain groups of fans can exert pressure on an author to keep doing the same thing that they loved earlier, and sometimes authors give in to this. Most fans strike me as being pretty decent people, however.

ASM: Looking back at the timeline of science fiction, how has fandom changed from those early years until today?

GKW: As I said, most fan activity has long since migrated to the web, and since I was never really involved in fandom as a kid, I can’t speak personally about what it was like back then. Today, everyone has a platform, and I think fans have become more balkanized—pulp fans, heroic fantasy fans, space opera fans, media and gaming fans, etc. But when people complain about bad online behavior and flame wars, I think of the sort of petty rivalries and zine wars that apparently were just as common back in the beginning of fandom in the 1930s.

ASM: Famously, you have developed your Theory of Science Fiction as it relates to how we perceive the genre. For those not familiar with your theory, please explain it.

ASM: Famously, you have developed your Theory of Science Fiction as it relates to how we perceive the genre. For those not familiar with your theory, please explain it.

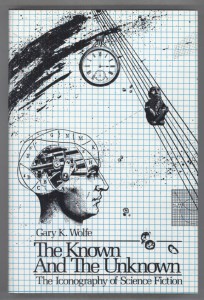

GKW: I don’t think I’ve ever labeled anything I’ve written as a “theory of SF,” so I’m not sure how to answer this. My first book on SF was called The Known and the Unknown, and it argued that a lot of SF takes place in the tension between those two things, developing specific iconographies involving settings (wastelands, cities) or beings (robots, monsters, aliens) that seemed to embed this tension. I think there’s still something to that; SF hasn’t generally been driven mostly by plots (like mysteries) or settings (like Westerns), though it borrows freely from those and other genres. But SF has become so diversified in the last several decades that I don’t think any one theoretical approach can account for what it does in all its varieties.

ASM: What are you working on now that we can look forward to reading?

GKW: Well, I hope to do some further work with the Library of America, I’ve more or less promised to write a couple of single-author studies, and another publisher has approached me about a large reference work, but there’s nothing in the works at the moment other than reviews and essays. The most recent essay is in Parabolas of Science Fiction, edited by Brian Attebery and Veronica Hollinger, which came out last year. It’s a piece on alternate cosmologies, as opposed to just alternate histories.

ASM: Thank you for joining us today. We greatly appreciate the critical eye and deep insights you have brought to the industry. Our understanding and appreciation of fantastic fiction is made more complete by your work. Before you go, is there anything else you would like to share with the readers of Amazing Stories?

GKW: Only to congratulate you on this latest incarnation of Amazing Stories and to wish you the best of luck. As you’re well aware, this is one of the iconic titles in SF history, and I hope you can keep it going until well after its 90th anniversary in a couple of years.