Because much of what we treasure is that which has lasted (preferably for centuries, if not thousands of years) the last “Hierarchy” I will deal with, and perhaps the most important one, has to do with MEDIUM, or permanence of materials.

WHAT I MEAN BY PERMANENCE

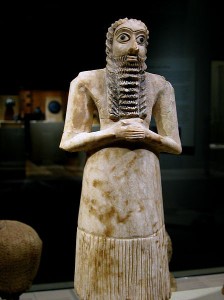

Approximately 39,000 years before we celebrated the very first “New Year’s Day”—a tradition which is reckoned as beginning in 45 B.C., when the Julian calendar first took effect in the Roman Empire—humans were already creating art. The earliest paintings were cave paintings, created during prehistoric/paleolithic (early stone age) times. We don’t know the exact purpose of them, or exactly who painted them, or if men/women/children were responsible for them, or if they were prompted by religion/social or hunting rituals or purely for decoration. What we DO know is that they were the first watercolor paintings made by human hands, out of raw pigments like ochre (iron oxide; yellow to dark orange to brown) hematite (reddish), manganese oxide (sienna brown) and charcoal . . . and that they have lasted for 40,000 years. Similarly long-lasting have been what we call “Venus figurines,” prehistoric statuettes of women dating from the Upper Paleolithic, about 35,000 ago, carved from soft stone, bone or ivory. In a relatively short time there was pottery and ceramics (Neolithic, or New Stone Age) and by the time Ancient Egyptians were carving sarcophagi, they were painting them in tempera (pigments with a binder, like egg yolks, hence “egg tempera”). The earliest existing intact painting brush was found in a Chinese tomb dating from the Warring States period (475-221 BCE)—used for paintings and calligraphy done in black ink made from pine soot and animal glue (nowadays called India Ink) on silk or paper, and these works have lasted for millennia. Oil paintings were first used for Buddhist paintings by Indian and Chinese artists starting 500 CE and became the principal medium for Western artists by the 15th Century.

The point of this history lesson? Cave paintings still exist in over 340 caves; we still have 900 panel “mummy portraits” painted in tempera from the Coptic Period in Egypt, 2000 years ago; we have bronze sculptures from the Greeks and parchments from Biblical times; painted pots from China and brush-painted manuscripts from China from 500 BCE; we have hundreds of examples of oil paintings dating from the Renaissance, most remarkably (according to many) the Mona Lisa (1503). And what do they have in common? The relative permanence of the materials used.

What don’t we have? Good, long-term solutions for documenting and preserving artworks created with computer-based, digital technologies, such as: digital art, computer graphics, computer animation, internet art, virtual art, video games, and more. And, New Media artists, by definition, are no help in this regard; they are concerned with contemporary production, not longevity. As a result, archival collections must now deal with a wide array of media and cultural objects, many of which suffer from a very short life expectancy. These mediums face serious preservation issues as the technologies used to deliver them become obsolete, and the time between creation and that obsolescence becomes increasingly shorter.

Lack of worry about longevity is not limited to “new media” artists. While the jury is still out on other mediums invented in the last 100-150 years or so, such as photographs, acrylics, and polymer clays (Sculpey and FIMO)—perhaps unsurprisingly—permanence hasn’t been high on the list for many artists for some time. This may be because, and unlike those carving in stone 2000 years ago, artists are not being driven by the desire to make lasting testaments to our occupation of the earth. Surely Frazetta wasn’t thinking of posterity when he used water-based ‘magic markers’ to color in his reproductions of line drawings! Animation cels from the 1920s-1950s made from cellulose nitrate have shriveled, pulp paper has crumbled, and even the paper used in paperback books from the 1960s has started to brown and brittle—when books from the 1700s are still bright and supple.

But it’s the general attitude that “permanence is irrelevant” that most defines and separates New Media artists from the so-called Traditionalists. The artist Eva Hesse, Aware of the instability of materials like fiberglass, which discolors and deteriorates over time, said, “Life doesn’t last; art doesn’t last. It doesn’t matter.”

THE HIERARCHY AS WE KNOW IT

Rightly or wrongly, therefore: Traditional “fine” artists, as well as many collectors, are of the opinion that works in pastels are better than those in colored pencil, that watercolors are better than pastels, that acrylics are better than watercolors, and that oil paintings are better than paintings in acrylics. For the same reasons, works on paper are lesser than works on art board (still paper), which are lesser than works on canvas. By the same reasoning, sculptures cast in bronze out-rank those in stone, which outranks wood, which beats out just about any other material, like resin, clay etc. What do these ranking orderings have in common? The relative permanence of the materials. And in general, these rankings affect the prices of art.

This hierarchy can be—and has been—extended with each introduction of a tool or process. “Hand-brush” is better than “air-brush” and “any easel work” is better than any “digital work.” Based on the ideas, respectively, that (1) hand-brushed works are intrinsically more “permanent” because restorers can usually emulate the paint strokes and color values with viewers not being the wiser, while fixes to airbrushing can’t be camouflaged, and are virtually impossible to hide and (2) with digital art, there is no tangible record of the art at its inception. The fear is: here today, and gone tomorrow. As in “404 Server Error.”

For collectors comfortable with traditional media there is something worse than the fading of watercolors, or the non-light-fastness of dyes and inks (the impermanence of certain paint media) and that is . . . the ephemeral nature of digital art. Oh, they know that—like oil paints on canvas 500 years ago, photography 100 years ago, and acrylics about 60 years ago—”digital” is the new kid on the art block, the new medium that makes new visions possible. But for hierarchists who revere permanence, there remains one BIG problem: Unlike all these media, there is nothing physical to hang onto, that one can call “the one and only.” And the same relative ease with which changes can be made, the very efficiency of the medium, is what scares collectors who cherish the concept of art “lasting through the ages.” With traditional media some work is required to destroy it: fire, breakage, knives, earthquakes. With digital art, just press “delete.”

What do you think? Do you subscribe to the idea of hierarchies? Can you think of more? Remember, the stature of what you collect, expressed in the relative $$$ value of what you collected, is being affected by these concepts every day. Will these influence what you buy? To review:

1. “arts” are better than “crafts”

2. “fine art” is better than “illustration”

3. art done “for love” is better than art done “for money”

4. “one-of-a-kinds”are better than “multiples” which are better than “reproductions”

5. art that is signed are better than art that is unsigned

6. art by someone “famous” is better than art by someone unknown

7. art that costs a lot is better than art that costs a little

8. art that is created by hand is better than art created by machine.

9. art that is permanent is better than art that is “fleeting”

10? Your input here.