Everything I know about writing science fiction, reading it, and understanding it, I learned from Edgar Allan Poe, specifically his one story, “The Fall of the House of Usher”. This goes for all of world literature as well. It’s all in that one story: how stories work, what they’re about, and why they have had the impact on us that they’ve had. Here’s how stories work.

Professors of literature (and, admittedly I am one) will often teach the short story (or the novel) as mysterious objects that often defy comprehension or understanding. Professors seemingly do this because the Great Authors are “deep” and their works impenetrable and, of course, Objects of Great and Sacred Art. This is a useful conceit that allows some people (I’ve known a few) to take on the mantle of authority even though they’re really masking their lack of understanding over how stories truly work. They won’t admit that they don’t understand a story (or a poem or a novel) and many graduate students–I was one–are left wondering why certain works in literature are considered great. Well, I’m here to turn you on to a little secret, a secret that you probably knew, but I’m going to put it into a different kind of language and use a single graphic illustration.

It starts with Poe. Why is “The Fall of the House of Usher” so effective? True, it’s a horror story. It might also be a ghost story (because it’s possible that the speaker of the tale only imagines that Madeline might be standing in the doorway to the crypt she was buried in). And the dramatic collapse of the house into the earth in the last paragraph might be real or it might be part of the speaker’s hypochondria . . . for we know he’s sensitive and we’ve already seen how much he’s absorbed Roderick Usher’s own hypersensitivity. We get a clue to this in the opening paragraph. In fact, everything we need to know about the story is in the first paragraph.

During the whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country ; and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher.

Like all good stories, it begins in medias res, that is to say in the middle of the action. But who’s action? Is it the ride on horseback to see a friend in autumn? Or is it in the middle of the speaker’s life? It’s the latter. And this is the secret: this incident is the most important occurrence in this man’s life ever. Nothing else will ever matter to this character ever again. He’s telling us something important about an incident in his life, but he’s also telling us something important about his mental state. He’s a chronic depressive. Look at the words in the opening lines quoted above. “Dull, dark, and soundless day” where “the clouds” hang “oppressively low”. He has been traveling alone along a “singularly dreary” tract of country lane and when he sees the House of Usher, he describes it as dreary. These aren’t throwaway words. Poe has chosen them carefully. The narrator, intentionally or not, is telling us something about himself that might explain what he sees at the end of the story.

Remember also that this is a first-person narrative. It’s being written down after the incident has taken place, perhaps as an act of mulling-through what’s just happened, trying to figure it out. But remember I said earlier that this was happening in medias res. This concept comes to us from Aristotle who wanted to understand why The Iliad worked so powerfully on the imagination. He concluded that the story was told in the middle of the action (and quite close to the end of the narrative). Poe is doing the same here. Stories are what they are because they are immediate. They don’t begin with the birth of the hero, his (or her) life, then his (or her) death. And stories aren’t about any old moment in a protagonist’s life. It’s about the moment. The moment when everything changed for them, or when they themselves were changed forever.

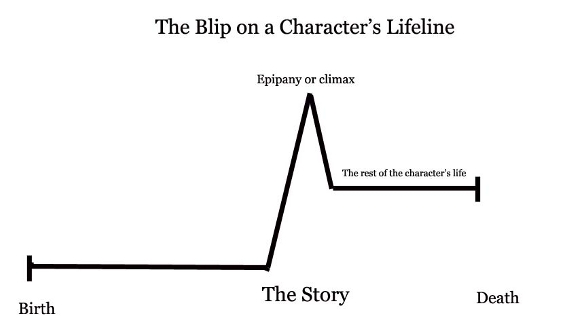

So here’s the secret to understanding stories. I call the moment of the short story as a “Blip on the Lifeline”. Picture a person’s life as a long line interrupted by a crucial event. This “blip” is the story. The elevated line extending toward the character’s death is the elevated nature of his or her life (unless they die).

Here’s what I have in mind

The lower elevated line is the character’s life before the moment of conflict when some drastic action needs to take place to resolve the situation. After it, the character (or characters) are changed forever. A story where the line after the blip comes down to the original baseline is a failure. Few stories do this, but there are some.

In the old days before franchises, serialization, sequels and trilogies and quartets and share-universe stories, science fiction writers often told one-of stories. A.E. Van Vogt’s story “The Weapon Shop” is a one-of. As is Harlan Ellison’s “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ said the Ticktockman’. Think of the great science fiction stories such as Jerome Bixby’s “It’s a Good Life”. The “blip” is really the collective experiences of the village trapped by the evil mind of the mutant boy. Think of Heinlein’s novel, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress or Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle. These are stories where the “blips” belong to all of the characters (as it is in Tolstoy’s War and Peace or Thomas Pynchon’s great semi-science fiction novel, Gravity’s Rainbow).

This is why I’ve written so harshly in my blog entries about novels in series. They tell us in ontological terms that the story being told is not a “blip” because we know that there are other adventures to come. They’re fun to read, true. And the movies are fun to watch as well. But the emotional impact of these stories is far less than the singular moment in the life of a character who experiences enormous change. This is why Philip K. Dick is my favorite author. He never wrote a sequel or a multiple of stories around a single character. Nowadays that’s all writers in our field do . . . and they do it for money only. This is why I’ve always believed that a story worth telling, is worth telling only once. Are we interested in Huck Finn’s life after The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn? Not really. Are we interested in what happens to Frederic Henry after he loses Catherine at the end of A Farewell to Arms? No. What happens to Jason Compson after The Sound and the Fury? Who cares? It’s the moment (or the collective “blip”) that is the novel The Sound and the Fury that only concerns us. We come to know Jason as well as the other members of the Compson family completely. There are no other blips.

This is why I never read sequels (unless they’re extremely well written and make sense in their totality, such as the tale of a family as in the Dune Trilogy or the rise and fall of an empire as in David Wingrove’s incredible Chung Kuo series). Batman, yes. Yes to Wolverine and John McClane. But I don’t care about characters beyond their single moment in time. The other moments are just about publishers removing money from your savings account. That’s all.You want to read all four (and now five) of the Ender’s Game sequels? Go for it. Do you learn anything more about Ender beyond the first book. Not really. Do you give Orson Scott Card and Tor Books more of your hard-earned money. You bet. I won’t, but you have my permission to squander both your time and your money on endless sequels. But I heartily recommend the one-ofs in literature. Try Thomas Pynchon. Try Salmon Rushdie. Try Philip K. Dick if you haven’t already.

–Paul Cook