March is here, and that means it is time to move into a new Crossroads series. For some reason, March always brings to mind melting snow, spring’s inexorable creep across the plains, cold mountains withstanding the coming warmth. In other words, March puts me in a western frame of mind. Which is why this month, I’m going to be exploring the relationship between westerns and speculative fiction.

As always, I am indebted to many other scholars and writers, who have done painstaking research from which I have benefited greatly. I’d like to particularly thank Mary Lea Bandy and Kevin Stoehr for their Ride, Boldly Ride: The Evolution of the American Western, JoEllen Shively for her viewer response research on Western cinema, Paul K. Alkon for Science Fiction Before 1900

and Brooks Landon for Science Fiction After 1900

. If I’ve made any big missteps in my analysis, they are entirely my own.

Shared Roots of Popularity

As you can probably tell, I love books. I love reading. And I love reading in all kinds of genres, although my heart is firmly wedded to speculative fiction. But to really explore the relationship between the western genre and speculative fiction, I’m afraid books are only part of the story. Film and television – and the immense popularity of the western on the big and small screens – has had as much or more influence on speculative fiction as western print has.

The western has always been a multimedia genre: back in the late 19th century, dime novels took off featuring the adventures of Buffalo Bill Cody, Wild Bill Hickock, Jesse James, Wyatt Earp, and other colorful – historical! – personages of the frontier. At the same time, some of these individuals (notably, Buffalo Bill Cody and to a lesser degree Wild Bill Hickock) tried to capitalize on their new-found notoriety by taking to the stage.

Why were western stories – whether on paper, or on the stage, or later in silent movies – so popular? Yes, they were entertaining, accessible, and (most importantly) cheap, yet even three such powerful reasons cannot fully explain the degree of the genre’s popularity. I think the real reason is because the metaphors, symbols, and plot structures of the genre enabled an audience traumatized by the Civil War to construct a new mythology, a new framework for personal values divorced from the ethical debates that had gripped the nation so violently for so long. By tapping into the manifest destiny ethos, the western genre enabled both southerners and northerners to share a common set of values, to identify with the same heroes, and to regain a sense of optimism however tinged by shadow and blood.

The same yearning for optimism, the same manifest destiny ethos, lies at the heart of much speculative fiction (science fiction in particular). Exploration, the taming of a foreign and dangerous environment, is a common theme in both the western and speculative fiction. What, after all, are Ray Bradbury’s Mars (The Martian Chronicles), James Blish’s Lithia (A Case of Conscience

), or Robert A. Heinlein’s alternate future (Farnham’s Freehold

) if not frontiers to

conquer subjugate explore?

Western DNA in Speculative Fiction

The western hero – the loner separated from family, friendship, and community yet possessing an unswerving moral code independent and superseding any civil law – stands (or rides) at the heart of the western’s appeal, whether in print (e.g. Ned Buntline’s Buffalo Bill, the King of the Border Men, Owen Wister’s The Virginian, Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage

, Max Brand’s Destry Rides Again

, Jack Schaefer’s Shane

, Larry McMurty’s Lonesome Dove

, etc.), on film (e.g. Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery

, John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

, Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars

, or Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained

), or on television (e.g. The Lone Ranger

, Lonesome Dove

, Bonanza

, etc.).

This heroic archetype translates seamlessly to speculative fiction, and has throughout that genre’s history. We can see juvenile versions of the western hero wedded to the science fictional scientist-hero in the dime novel Edisonades of Harry Cohen and Luis Senarens (i.e. the Frank Reade and Frank Reade Jr. stories), more mature versions transplanted out of the western environment in the pulp fantasies of Robert E. Howard (particularly in the Conan and Solomon Kane

stories), or futuristic versions on screen (e.g. Han Solo in Star Wars

, Rick Deckard in Blade Runner

, Malcolm Reynolds in Firefly

, etc.). Next week, we’ll take an in-depth look at this archetype, and the ways that both science fiction and fantasy explore it.

Yet the western hero and the good guy/bad guy plot conventions that accompany him are not the only feature shared by the western and speculative fiction: world-building and the Other are just as important.

Most western readers never set foot in the frontier, even when it still existed. As a result, the environment and the social mores/conventions that applied there were and remain as foreign as those of an alien planet. This creates an analogous challenge for the western author as for the speculative fiction author: to communicate an environment that is believable, palpable, and evocative. Westerns need just as much world-building as speculative fiction, however their approach to this challenge is often very different. As I’ll get into two weeks from now, I think speculative fiction writers can learn something from the evocative way in which western writers construct their environments.

Of course, a big part of those environments are the people we meet there. Westerns explore the Other to the same degree as speculative fiction does, however rather than present the Other as aliens/fairies/other species, they instead portray them as American Indians (e.g. in Michael Blake’s Dances with Wolves), as Mormons (e.g. in Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage

), as Mexicans (e.g. in Two Mules For Sister Sara

), etc. In still other cases, westerns explore the other by contrasting different generations of frontiersmen (e.g. the conflict between homesteaders and earlier pioneers in Shane

).

Westerns as a Commercial Model for Speculative Fiction?

Yet the creative similarities between westerns and speculative fiction may ultimately be less important than their commercial similarities. As film technology improved, early directors were able to bring the western genre to life on the silver screen. It was far easier to do so with cowboys than with contemporary steam-powered automatons.

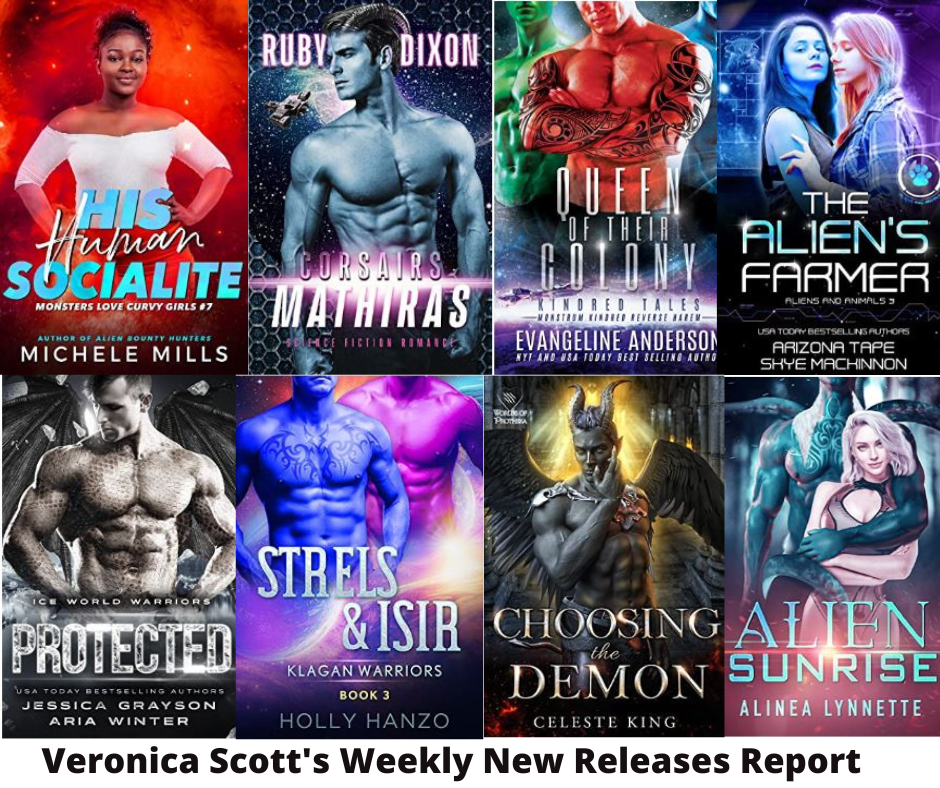

The commercial path of the western genre saw film and television eclipse the printed form, and ultimately lead to an over-saturation in the marketplace which damaged sales of western genre novels. Today, the western section in our local bookstores are either tiny or nonexistent. Yet a hundred years ago, the western was the largest genre in print.

As we look at our multimedia landscape today, we find it saturated with speculative fiction. Whether we’re talking about films, video games, or television, our media consumption is saturated with speculative themes and devices. Will this one day lead to the type of over-saturation that preceded the western’s decline? Or is speculative fiction protected against this by its thematic breadth?

I don’t know if we’ll find an answer in the coming weeks, but I’m looking forward to exploring it with you. Next week, we’ll be diving into that core of the western genre: the western hero. ‘Til then, what are your favorite westerns and how do they relate to your favorite SFnal stories?

Hi-yo, Silver! Away!

The following comment was originally posted over on my blog by calmgrove, who granted me permission to cross-post it hear:

And here is my response:

Zane Grey wrote my favorite westerns. The Lone Star Ranger sticks out most in my head. The details he had in his stories captured the old west.

I think Science Fiction and Fantasy will not experience the same waning interest because of their breadth. Westerns are after all westerns. They are limited in setting and scope. Science fiction and fantasy are limitless.

Mike Resnick is one of my favorite science fiction authors. Many of his novels are taken right out of the old west set in the distant future: gunfights, frontier towns, heroic figures, bounty hunters.

I look forward to your next post.

Thanks,

RKT

RKT – Thanks! You're absolutely right about Zane Grey's "capturing" of the Old West – the way he describes the environment and ties the imagery back into his characters' emotional arc is very impressive (and I'll be talking a lot about two weeks from now when I dive into western world-building!).

Mike Resnick has definitely written a lot of great western-themed stories. Recently, he's also waded into the western-tinged world of steampunk with his Weird West tales from Pyr (The Buntline Special, The Doctor and the Kid, and The Doctor and the Rough Rider), which have all been great fun.

Wellll, since you asked. My favorite western film is "Comanche Station." This is a film directed by Budd Boetticher starring Randolph Scott. One of a series of films they shot out at Lone Pine Calif, in the late fifties, early sixties, near the Sierra Nevada Mountains. They have a sort of cult following. Most were written by Burt Kennedy. I was so inspried by Comanche Station I decided to rewrite it as a space opera short story. It eventually became the first chapter of my spacewestern novel, "Jack Brand." I was intrigued to see how many western tropes I could translate into space opera. I used the novel to "pay homage" to films and stories written by Sam Peckinpah, Sergio Leone, and others for the 12 chapters of the book. I think it turned out to be a fairly successful genre mashup. The cross pollination of science fiction and the western can really yield some interesting hybrid results.

Absolutely! Comanche Station is a really fascinating little film. Maybe not as classic as Ford's The Searchers, but still offers lots of interesting discussion. I'll actually be coming back to both it, and The Searchers in a couple of weeks when I talk about westerns and science fiction's relationship to the Other.

Interesting parallels. I think a lot of this applies to storytelling in general, going way back. As for the staying power of science fiction, I think it will thrive as long as it continues to embrace new frontiers. A good example of SF accepting new frontiers is cyberspace. If science fiction stops being open to the new, it will no longer be science fiction, which is one way for it to die – a semantic death. Of course the future has a will of its own and may rendering my opinion as nothing more than a whim of ignorance.

Westerns, I think, hew quite closely to very old school mythic hero structures. There's a lot of the "knight of doleful countenance" to them. I think in some ways, this may have been the genre's overarching problem: such a focus on such a hero can only support so many variations on the story, and when they're all published/filmed/released in such close proximity it can naturally lead to over-saturation. But I think SF/F has more hero archetypes available to it, which gives it that greater depth. At least, that's what I hope. 😉