Brian Aldiss identified Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as the first science fiction novel in his seminal history The Billion Year Spree. Although the genre often looks back on this work as its starting point, it was published more than a century before Hugo Gernsback named the field. When thinking of early twentieth century science fiction, men were the predominant authors, whether Edgar Rice Burroughs, A. Merritt, or Murray Leinster. However, women were writing tales of the occult during this period and eventually, one of them would also begin to write science fiction.

The July 1926 issue of Weird Tales included a short story entitled “A Runaway World,” by Clare Winger Harris. Although the issue also contained a story by Elizabeth Adt Wenzler and earlier issues had also included supernatural tales written by women, Harris’s story was different because it was a tale of science fiction rather than the occult.

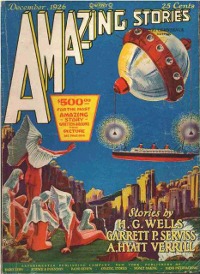

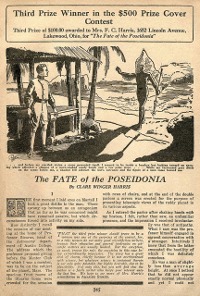

In December of 1926, Hugo Gernsback ran a contest in his new science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, asking his readers to provide a story that explained the cover of that month’s issue. The cover depicted several nearly naked figure on a cliff watching an ocean liner floating over a strange city. Gernsback was surprised to receive an entry from an author with a woman’s name. Although her story, “The Fate of the Poseidonia” only took third prize in the contest, when Harris’s name appeared next to it in the June 1927 issue, hers was the only female name in the table of contents and, in fact was the first female name to have a story appear in Amazing Stories. In fact, in breaking the gender barrier, she caused Gernsback to write, “That the third prize winner should prove to be a woman was one of the surprises of the contest, for, as a rule, women do not make good scientification writers, because their education and general tendencies on scientific matters are usually limited. But the exception, as usual, proves the rule, the exception in this case being extraordinarily impressive.”

In December of 1926, Hugo Gernsback ran a contest in his new science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, asking his readers to provide a story that explained the cover of that month’s issue. The cover depicted several nearly naked figure on a cliff watching an ocean liner floating over a strange city. Gernsback was surprised to receive an entry from an author with a woman’s name. Although her story, “The Fate of the Poseidonia” only took third prize in the contest, when Harris’s name appeared next to it in the June 1927 issue, hers was the only female name in the table of contents and, in fact was the first female name to have a story appear in Amazing Stories. In fact, in breaking the gender barrier, she caused Gernsback to write, “That the third prize winner should prove to be a woman was one of the surprises of the contest, for, as a rule, women do not make good scientification writers, because their education and general tendencies on scientific matters are usually limited. But the exception, as usual, proves the rule, the exception in this case being extraordinarily impressive.”

Harris’s career was relatively short. Between the appearance of “A Runaway World” in 1927 and her final story, “The Ape Cycle,” in early 1930, she only published eleven stories, including one in conjunction with Miles J. Breuer, a reasonably prolific author who debuted in the pages of Amazing Stories six months after Harris’s first story was published. Her stories appeared not only in Amazing and Weird Tales, but also in Wonder Stories Quarterly and Amazing Stories Quarterly. In 1947, Harris collected all eleven of her stories and published them through a vanity publisher as Away from the Here and Now, a book which was brought back into print by Richard Lupoff’s Surinam Turtle Press in 2011.

For the most part, Harris’s prose is serviceable in that it allows her to express her innovative and imaginative ideas, however, at times it does get in the way of the story. Writing about her debut story in Science Fiction: The Early Years, Everett Bleiler described “A Runaway World” as “Amateurishly presented, though a good idea for the time.” Describing various of Harris’s works in his follow-up book, Science Fiction: The Gernsback Years, Bleiler uses the word “amateur” several more times, even when he praises her ideas. Even Lupoff, one of Harris’s biggest boosters, admits “today’s readers may find her prose creaky and old-fashioned…”

For the most part, Harris’s prose is serviceable in that it allows her to express her innovative and imaginative ideas, however, at times it does get in the way of the story. Writing about her debut story in Science Fiction: The Early Years, Everett Bleiler described “A Runaway World” as “Amateurishly presented, though a good idea for the time.” Describing various of Harris’s works in his follow-up book, Science Fiction: The Gernsback Years, Bleiler uses the word “amateur” several more times, even when he praises her ideas. Even Lupoff, one of Harris’s biggest boosters, admits “today’s readers may find her prose creaky and old-fashioned…”

Harris’s eleven short stories cover a wide range of tropes that are recognizable to modern readers of science fiction. Space travel features in “Baby on Neptune” while “A Certain Soldier” is a time travel story. “The Menace of Mars,” as the title suggests, deals with an alien invasion, and aliens themselves feature in several of her stories. Both “The Evolutionary Monstrosity” and “The Ape Cycle” deal with attempts to alter natural evolution, with the latter being reminiscent of Pierre Boulle’s Planet of the Apes.

Perhaps her weakest story is the one which introduced me to her works. “The Fifth Dimension,” a tale of predestination, déjà vu, and clairvoyance, suffers from not only its length, being the shortest of Harris’s published tales, but from a stilted and dated use of dialogue which doesn’t represent the way people ever spoke. As with her earliest works, “The Fifth Dimension” is less of a story and more of a description of events, with little or no activity on the part of her protagonist. James Griffin in “A Runaway World,” George Gregory in “The Fate of The Poseidonia,” and the spouses of “The Fifth Dimension” have little, if any, active role in driving the story, although Harris would eventually learn to make her characters more proactive.

In “The Evolutionary Monstrosity,” her narrator, Frank Caldwell, doesn’t take a particularly active role in the experimentation of his college friends, Ted Marston and Irwin Staley, but he does eventually take action when Marston’s research appears to wander a little too close to the “Man was not meant to know” category. Even more active is Edgar Hamilton, who drugs his girlfriend in an attempt to slow down her aging process so she will be willing to marry him. Hamilton’s plans go awry and he takes further measures to rectify them, perhaps being the most active of all of Harris’s protagonists.

With only eleven published stories, there is something in two of them, notably “The Fate of The Poseidonia” and “The Artificial Man” that stands out. Both of those stories revolve around George Gregory, although the stories are not linked in any other way. The George Gregory in the first is engaged to Margaret Landon, but screws up his romance due to his curiosity and his rivalry with Martell. In the latter work, George Gregory is a happy-go-lucky man engaged to Rosalind Nelson, until a series of accidents cause him to turn to a crank theory and lose both his optimistic outlook and his girl. The fact that both George Gregorys lose their fiancées leads to the question of whether there was a George Gregory in Clare Winger’s life at one time and what their relationship was.

Unfortunately, little is known about Clare Winger Harris’s life. She was born Clare Winger in Freeport, Illinois on January 18, 1891. She attended Smith College in Massachusetts and in 1912 she married Frank Harris, an engineer. After World War I, the couple moved first to Iowa, and later to Cleveland, Ohio. Her three sons, Clyde, Donald, and Lynn, were born between 1915 and 1918. In the biography that accompanied her book, she explained that she quit writing in order to focus on raising and educating her children, who would have ranged in age from 12 to 15 when her last story appeared.

Harris wasn’t the first woman to write science fiction. Prior to her debut, Gertrude Barrows Bennett had published science fiction from 1904 through 1923, influencing A. Merritt and H. P. Lovecraft. However, as most of Bennett’s stories were published under the pseudonym Francis Stevens, she was not recognized as being a female author until Lloyd Arthur Eshbach announced her real identity in a reprint of her 1918 novel The Citadel of Fear in 1952, four years after Bennett’s death.

Cyrano de Bergerac's Journey to the Moon published 1657

Ho also write A Journey to the Sun

His modes of travel and experiences were far fetches but I'd still consider them Science Fiction.