OBIR: Occasional Biased and Ignorant Reviews reflecting this reader’s opinion.

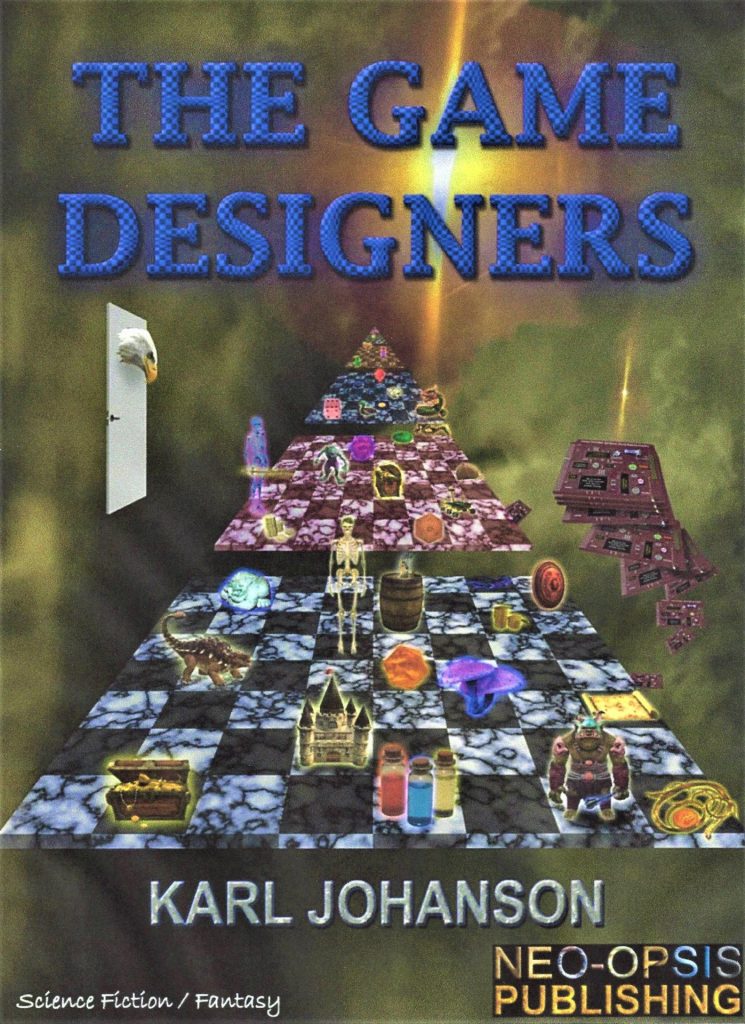

The Game Designers – by Karl Johanson

Publisher: Neo-opsis Publishing, Victoria, B.C., Canada , 2021.

Cover Art by Karl Johanson. Interior Art by Stephanie Ann Johanson.

Premise:

Are Game Designers better than the rest of us at coping with life after death?

Review:

This is an odd one. Offbeat. Unusual. I’d say it is concept-driven, which is the kind of genre-fiction I prefer. I mean, when New Wave SF started popping up in the 1970s I stopped reading SF for several years. I had no tolerance for genre fiction fixated on character and internal angst. I read SF to glory in sense of wonder concepts, not people’s personal problems. I felt SF had abandoned me.

But then my friend Stan G. Hyde (who, among other things, taught English literature, drama, and science fiction courses in high school) pointed me in the direction of modern SF writers who combined the best of old wave and new wave techniques to write solidly entertaining works exploring and expanding the parameters of science fiction in innovative new ways. So, I got back into reading science fiction and today revel in the wide and diverse field it has become. Still, I retain a special place in my heart for fiction that is primarily based on concept, as long as it is original and exciting.

The Game Designers is concept-driven through and through, but shifts focus twice, narrowing each time. First comes the set-up, then the implications of the set-up for a particular task, and then speculation as to what that task will ultimately evolve into. Every step of the way, but particularly during the first part, cynical satire is employed to demonstrate our tendency to embrace shenanigans no matter what the ethical and moral considerations of a given era or situation are supposed to be. That’s why we have laws. Not to prevent crime (which they never do) but simply to provide a yardstick to measure our behaviour. At least, that’s my theory. We always remain distressingly human. I like genre fiction that reinforces my belief, especially if it is amusing and full of nifty ideas, and this book fits the bill.

NOTE: My division of the book into three distinct parts is my interpretation for critical purposes. In fact the book evolves, with each “part” meshing and melding in an overlapping fashion. Nevertheless the final chapters are quite different from the beginning chapters, so I’m examining each of the three “parts” in turn as distinct entities because it makes my job as a critic easier. We critics are a lazy bunch.

PART ONE: Andrew wakes up in the afterlife. Fortunately there’s a mentor on hand to help him materialise in corporal form and adjust to the new situation. He embarks on a quest to understand his new environment, not unlike learning the rules of a game he’s just been invited to play. To me there’s a clear implication that, as a game designer, he already possesses the skill set necessary to succeed in his quest.

One of the reasons I’m an atheist is that no one has ever been able to make the traditional Christian concept of heaven seem attractive to me. Or, as Mark Twain put it, he’d rather go to hell because that’s where all the interesting people are.

This book’s interpretation of the afterlife is neither heaven nor hell, or perhaps it is a combination of both. It seems to be an alternate-world Earth inhabited by every human being who ever lived and died. A bit crowded. If only with one’s relatives going back thousands of years. Think about it. Think about the old saying “You can choose your friends but not your relatives.” Suppose your Grandfather never approved of you. What makes you think he’s going to change his mind now that you are both dead? He’s already had years in the afterlife to convince his Grandparents you’re no good. How do you react when hundreds of your relations refuse to talk to you? If you were obsessed with being an outlier in your own family before, how do you cope with an afterlife magnifying that situation a thousand fold?

Or, for that matter, how do you cope with family continuing to change after they’re dead? What a surprise to learn that your amiable Grandpa and Grandma, seemingly a loving couple, decided to get a divorce a month after they died and are spending eternity with youth restored and locked in an endless quest for as many sexual partners as they can handle? A tad embarrassing.

And what about criminals? Every criminal who ever lived has been “reborn.” Including all the sociopath serial-killers. Moving about the streets after dark, or even during the day, is not safe at all. Sure, everyone is immortal, but all that means is you can be killed over and over again and it’s such a nuisance to take the time to reconstitute yourself. Plus pain is still pain in this afterlife. Trauma isn’t abolished; it is endlessly repeated unless you learn how to avoid it being inflicted on you, and that ain’t easy. Street smarts are hard to come by.

In short, the afterlife has all the problems humanity experienced on Earth, only now every single one of them co-exists simultaneously and will continue for all time. The original life on Earth is heaven by comparison. Bit of a bummer, that.

On the other hand, God or Gods being absent, the perpetual dead have the power to wish into existence whatever they want. Karl has a great deal of fun exploring the possibilities. People who died before movies were invented forming film societies for instance. Wishing for delectable food is popular, though not all are good at it. Some conjure up their dream cars. I would go for either a Rolls Royce Silver Ghost or a Stutz Bearcat. Indeed, the point is made that it’s almost impossible to find “average” automobiles in the afterlife. Nobody wants to drive those. For good or bad this afterlife is a wish fulfillment fantasy, in a sense a world ruled by magic. But there are limits. You can’t wish the afterlife out of existence. There are rules. Only by understanding the rules can you maximise your freedom of action.

One of the most frustrating rules is that a wish can be negated by a counter-wish. Karl plays with the idea that many would like to establish bases on the lunar surface. Gus Grissom, who died in the Apollo One fire, lives his dream of walking on the Moon. I find this very poignant, especially as my parents knew Gus and Betty from Wright Patterson days in the mid 1950s. I don’t recall events, being still in diapers at the time, but my older brother remembers how great Gus was with kids when assorted families from the base gathered at parties my parents threw. Consequently I’ve always had a soft spot for Gus. The idea that he is happily spending eternity exploring the Moon appeals to me. However, when Andrew arrives the afterlife space program is on hold because every time supporters wish for a successful liftoff, thousands of anti-space program people throw counter-wishes at the rockets and prevent them from launching. Thus real life politics plays a role in the afterlife.

These are just a few of the nifty concepts Karl explores in the set-up portion of the book. As if to say, “You think life is confusing and stressful in this life? Wait till you get to heaven. Then all hell breaks loose.”

PART TWO: A big part of life in the afterlife is boredom. Once you’ve done everything you want to do a few thousand times, there’s nothing to look forward to, and people, especially the unimaginative types, become unresponsive, as if on hold in some sort of coma. This happened fairly quickly to Stalin, though some of the dead think it was because he got bored with the millions of his victims walking up to him one after another to complain about his Gulag. At any rate, he shut down rather than cope. An interesting concept.

Gaming takes on fresh life in this afterlife. People like a challenge. Trouble is, everyone having wish fulfillment powers, it’s so easy to cheat. Andrew joins “Gaming Unlimited” to help design a game that cannot be cheated. Called “Riddlehead” it’s a sort of D&D board game heavily dependent on solving riddles. We see the initial design stages, then witness a full-fledged tournament akin to modern ones. You know, the kind that fill arenas with thousands of fans, are broadcast worldwide, and have huge cash prizes? That sort of thing. I’m spectacularly unfamiliar with the modern gaming world, but I gather that the shenanigans involving players attempting to cheat or at least take advantage of unnoticed loopholes are a satiric take on various types of gaming personalities and practices. It helps to be a gamer to appreciate the full nuances of this section.

Karl Johanson is, among other things, an experienced game designer. I suspect a great deal of insider information and frustrations has gone into this section and have no doubt serious gamers will find it a treat. However, not being much of a gamer, I also suspect many pertinent points may have flown past my head. All the same, I was able to follow along and appreciate much of the humour. I enjoyed it.

Besides, in parallel with the tournament are a bunch of vigilantes performing a game-like quest to prevent certain malcontents from acquiring nuclear weapons. After all, if you’re a villain, the fact that your victims are going to be “reborn” isn’t going to stop you from committing mass murder with weapons of mass destruction. I’m pretty sure there’s some subliminal commentary on the game-like nature of real life and the real-life nature of gaming here. I don’t think Karl is going quite so far as to suggest that gamers would be better at solving certain world problems than politicians, but maybe. Then again, he could be implying politicians are the biggest gamers of them all. Likely true, methinks.

PART THREE: Here all the main characters are immersed, as if “living” in a holodeck scenario, in a D&D-type game called “Time Runner II.” Going to Google, apparently the original “Time Runner” arcade game circa 1983 involved filling in the lines defining twenty rectangles while four killer droids chase you. It was described as “Repetitive, boring, and simplistic.” Methinks calling the game in this book “Time Runner II” is an insider joke fellow game designers would appreciate.

The game is, again, a D&D-type maze game, involving “Frost Caverns” and “Voo Voo Monsters” and the like. I assume elements of parody are involved but I’m not sure. To me, with my limited gaming experience, everything seems more-or-less credible, so I may be missing aspects which serious gamers would find outrageous. However, the interaction between the characters is entertaining. Still, being largely devoid of the interesting bits of afterlife extrapolation evident elsewhere in the book, this section was the least successful for me as a reader. Mainly because I never got into D&D either via a live game with a Dungeon Master and other people, or in any electronic version. It needs to be part of your background as a serious hobby interest for the final portion of the book to fully take hold of your imagination.

Oh, I once slew a dragon in D&D, and once accidentally unleashed a plague of vampires on my traveling companions, but I never got into it enough to want it to be a regular part of my life. I also put a few hundred hours into playing the Colecovision version of “The Legend of Zelda,” and currently have the first 3-d version of “Duke Nukem” in my computer, but I’m not really what you call a gamer. So the final third of the book is a bit distant for me and not quite something I can readily get into.

On the other hand, the fact that the book is titled The Game Designers, and written by a friend of long standing I’ve always known was a game designer, are clues enough to anticipate the focus would ultimately be on game design. Or rather the future of game design. The ending of the book is dependant on an evolution of technology which has yet to take place but may well be just around the corner. In that sense what had been a fantasy treatment of the afterlife ultimately winds up becoming predictive science fiction with all sorts of implications for the future of life in general. Pretty cool.

CONCLUSION:

The purpose of this book is to explore and parody game designing, which it does well, being based on the author’s own life experience. As such, it’s something of a narrow-niche book in terms of its target audience, which is gamers. If you love D&D maze games, this is a hoot to read, no question. For non-gamers, of marginal interest, perhaps.

Except… the opening set-up, a unique vision of life after death and all the problems it poses, is delivered in an imaginative and innovative Mark Twain at-his-cynical-best style that is genuinely amusing, perceptive, and stimulating. From the point of view of a non-gamer, the best part of the book.

So, is this fundamentally a divided book, a schizophrenic book? Some people will like the beginning, others will prefer the ending, such that everybody will skip over the portions of the book they don’t like?

No, the whole thing is fun to read. I suspect that science fiction fans in general will particularly enjoy Karl’s vision of the afterlife, and gamers will especially like all the gaming aspects, but that both will find the book as a whole entertaining and well worth reading.

To sum up, I’m glad I read it. But for me, it’s Karl’s hilarious extrapolations of what he figures the afterlife would really be like that will stick in my memory. He has a sharp and often subtle sense of humour, sometimes a rather dark sense of humour. Precisely the sort of thing I like to see in science fiction.

Or, to put it another way, if you are as weird as I am, you’ll really get a kick out of this book.

Check it out: < The Game Designer >