We have to talk about Robert Bloch in the column. The list of Science Fiction writers who have enough short story output that they could call Philip K. Dick lazy. Robert Bloch was one of the few.

Robert Bloch is an author most commonly remembered as the author of one novel. This is understandable. When you wrote a novel like Psycho, yes, that Psycho, made into one of Hitchcock’s greatest classics, you become Robert Bloch – the author of Psycho. Bloch’s career spans back to 1934 when he sold William Crawford the story Lillies to be published in a non-professional fanzine.. During that decade when he traded letters with Lovecraft and was one of the first players in his sandbox. The Opener of the Way was published in Weird Tales in 1936 and was a landmark at the time. He was an active member of the Milwaukee Fictioneers, which produced other landmark authors like Stanley G. Weinbaum and Fredric Brown. During an early visit to LA, he was also on a double date with Catherine L Moore and Henry Kuttner when they first went out. Bloch was a Science Fiction guy.

Bloch was published in SF, fantasy, horror, and mystery over the decades. He wrote for TV, even recycling some of his own published stories, like Boomstick Ride that was published in the 1957 issue of Super Science Fiction, for the Halloween episode of Star Trek called Catspaw. He dragged Lovecraft’s old ones into an episode of TOS that was still influencing the latest season of Strange New Worlds.

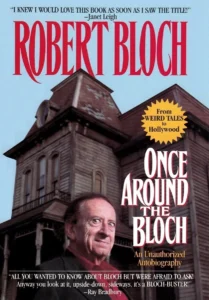

None of that matters for legacy when you are the author of a short and powerful novel like Psycho. Hitchcock’s film and the infamous shower scene. Psycho is classic for many reasons, and it is not a bad calling card for horror/Crime/suspense, but it has been interesting that Robert Bloch is rarely remembered for his science fiction, and he was prolific in the field in terms of Short stories. Funny thing, I wasn’t even sure he had written a true SF novel.

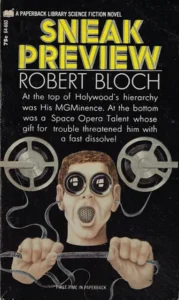

So imagine my surprise during a visit home to Indiana to find this novel in a free bin at the Ray Bradbury Center in Indianapolis. I somehow had never heard of it before, and when I read the concept, it just sounded totally bonkers. I didn’t know that it started as a short story in 1959, and much like many others at the time, he expanded the novella 12 years later.

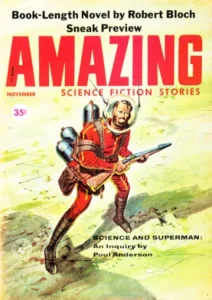

The first story was published (right here) in Amazing Stories; none of the other stories are by classic authors, although Poul Anderson has an essay. I tried to find the 59 version online, but the only scan of the issue I could find was missing the story, so I can’t compare the two versions. This was a PKD trick, it could have been the case that Bloch, like Dick, Bloch was asked to expand the idea by an editor. Both Bloch and Dick seemed to pump out stories to keep money coming in, I wonder if they took ideas that they thought were novels and sold a quick short story version first.

The 1959 to 1971 pipeline for this novel makes this novel even weirder. One thing I love about retro SF is how out of joint the projections of the future from the 50s feel. Adding to the bizarro nature of Sneak Preview is that it was updated in a very different world from when it was started.

What did Robert Bloch say about it? “Sneak Preview was originally written in 1959, at a time when alarm over the possibility of population explosion was not yet widespread. I wanted to voice my own concern about what I felt was a soon-to-be a major problem. When I came to expand the story, a dozen years later, the dangers of overpopulation had become common knowledge; consequently, instead of amplifying that element of the story, I decided to add a series of flashbacks which emphasized some of the factors which led to the formation of the society of the future as I envisioned it.”

Bloch appeared to be focused on the world-building; some of the weirdest and most hilarious moments are not the overpopulation and ecology issues, which are handled with a morse but beautifully written prologue about ecological devastation. This creates a beautiful whiplash when Bloch sets his satirical sights on Hollywood.

One must understand, going into updating this story into a novel, that Robert Bloch was a working writer in television and had one of his novels adapted by the most famous director in the world. His point of view on the world was shaped by living in LA and being directly part of the Hollywood system, so if he was going to write an SF satire, this work of insanity has roots that make some sense.

A plot description of Sneak Preview is totally bonkers. Set in the Hollywood dome, after war and environmental destruction have made most of America and Earth unlivable except for the domes. The survivors live on only thanks to the “planned society,” and the tight control is maintained by the popular media pumped out by the Hollywood industry, and at the top of the hierarchy is Archer, his MGMinence.

Graham is a “discontented talent” who writes Space Operas – these films are meant to be popular and maintain the social status quo. “Listen, Graham. Let me remind you that you’re writing for the space opera division. You’ve got one job, and that’s to please your immediate supervisor – me. And if you want to please me, you’ll stick to one plot, Bem meets Fem. That’s all.”

“I know,” Graham sighed. “Only I get sick of it, doing the same old thing again and again. Telling the same old story. Space travel is dangerous. other worlds are filled with danger and evil. And so forth.”

Bloch only wrote three episodes of Star Trek; however, I think this commentary is playing with the idea of Flash Gordon-like serials. It is significant if you consider this book hit shelves six years before Star Wars was a thing, and Lucas was still a USC student. It really is strange that a pre-blockbuster novel projecting SF as social conditioning.

“And so on,” Zank added. “You forget, it serves a purpose. Violence is outlawed here on Earth. We can’t show killings and torture and antisocial aggression. So we switched to other planets, transfer the aggressive tendencies of men to the bug-eyed monster. and at some point, punch home the idea that it’s better not to meddle with spaceflight. What’s the matter, sweetheart don’t tell me you’ve forgotten the basics.”

Bloch highlights a strength of weird fiction of all kinds, the ability to wrap politics in metaphor. I thought about V creator Kenneth Johnson, who, in the early 80s, wanted to do a modern adaptation of the Sinclair Lewis novel It Could Happen Here, but no one would green-light it. So he made the Nazis into lizards. In the tradition of Science fiction mocking itself, we can look back to fellow Milwaukee Fictioneer Fredric Brown’s What Mad Universe or Philip K Dick’s short story Waterspider. Asimov and Heinlein get name-checked, and I found myself wondering if Bloch was inspired by Phil. That said, as far back as the 30s, he wrote his friend Howie P into stories.

Bloch is not insulting the genre or fans, but suggesting a society that would use the genre first as a capitalist product and second as propaganda.

“Space operas are an important adjunct of social conditioning. The hero must be dark, the heroin must be blonde, the monster must be green, and the plot must be…”

Science Fiction as a capitalist product is only part of how the novel deals with the so-called ‘Planned society.’ Social control radiates from the media, but Bloch on the working class character, similar in a way to PKD. Certainly, Trocar a grave-digger, feels like a lost Dick working-class character. This passage is perhaps the best example.

“Not that spades were needed anymore. The automatic grave-digging machines were a great invention. And his time, Mr. Trocar had seen many such advances in the field, and he welcomed them all.

He had no patience with this outcry against automation, throwing people out of work? But there was always other work to replace the lost job, because there were always more people. And people needed services. Vital services, such as his.”

It should not be a big deal, but most SF writers focused their novels on military leaders, scientists or capital H heroes. This stuck out to me. The novel still is most focused on Graham, who is essentially a Hollywood hack living such a 1959 version of the future.

The domes, the planned society, the weird media-obsessed future are all super bizarro. The most hilarious world-building and satire is woven into all the Hollywood stuff. Bloch makes fun of the city a little, but he is mostly savaging the industry.

“In the great 21st Century Vox studios, in the city state of Hollywood, the top-level proceedings began slowly.

Sigmund squirmed uncomfortably in his seat, wishing he were in a posture chair. But of course, there were no posture chairs here in the conference suite.

It was a whim on the part of Archer, his MGMinence, the tall, thin, hot-faced man at the head of the table had deliberately chosen to surround himself with the quaint decor of olden times, including all the appearances of a medieval “executive suite.”

The studio hates the space operas even as they depend on them as a product. Graham sees classic science fiction as profane. Bloch knew his readers were fans and would find the idea of SF as filth to be funny.

“It was all pornography, of course, things he had heard of vaguely but never seen and not quite believed in; Filthy stuff by writers named Asimov and Heinlein and Clarke which had been openly peddled through the guise of science fiction. Despite his initial qualms, Graham found the material quite interesting from a clinical standpoint after all had in his own work space opera originally sprung from the outmoded and obscene sources that’s the way he’d always understood it.”

The heroes seemed ridiculous. If only Bloch had lived to see more genre fiction influenced by Dick, Brunner and himself that were more about characters. He seems to be implying the “idea-first” SF of Asimov and Clarke was essentially pornography. I can’t image what Graham would have thought about Malzberg who actually wrote a novel (Beyond Apollo) where an astronaut actually has sex with snake creatures from Venus. Speaking of Malzberg this next passage reminded me of Barry.

“Throughout, everything seemed to run absurd fantasies of omnipotence. The heroes were supposedly brilliant or at least pure intellects; nevertheless reacted to stress in terms of physical aggression throughout the narratives. They kept coming back for more punishment repeatedly, and even when exhausted, they seemed capable of one last superhuman effort, which resulted in the ultimate triumph.”

Bloch, in many ways, is protesting the Gernsbeck and Campbellian traditions here; he is not a new wave writer, as he was publishing in the golden age. Still, this feels like a new wave protest of the old guard. It is not exactly a dangerous vision, as it is a goofy, weird tongue-in-cheek novel.

Part of what makes this novel so bizarro is the heavy-handed message in the last couple of chapters. (Spoiler-phobic) Readers of this review, be warned. I am going to talk about this point. Robert Bloch was already 37 years into his SF career and not exactly a part of the rebellious youth movement that seemed to want to make a point about the struggle between generations.

“When psychologists and social scientists attempted to analyze the sources of aggression, back in the old days, they missed the really important one. Probably because they were so closely involved in the pattern themselves that they were unable to realize just how all-encompassing it was. Whatever the reasons, they did miss. They failed to recognize that the basic struggle in old fashioned society was not that of capital versus labor or male versus female, or civil authority versus military authority, or even science versus religion.

“The big clash was simply youth versus age.”

He is right, each generation tends to think the one before then doesn’t understand. Since this novel was written, Boomers butted heads with Gen X, we roll our eyes at Millennials, and Gen Z thinks Trump is a part of life. It is a point one I have not seen tackled so on the nose in SF before, but his method of getting there was just weird. In a great way.

I mean, the opening prologue about the California countryside outside of the domes is disturbing and powerful, almost as dark as Brunner’s ecological SF nightmares. Then the novel shifts into the Hollywood satire, hilarious technology that had me laughing like I was reading PKD, Sheckley or Douglas Adams. The shifting tone was a feature, not a bug. I went from laughing to this depressing scene about a high-tech birthing center that spits custom humans…

“In the Perth conditioning complex of the Denver Dome, one hundred and thirty-four life support capsules stood unattended as the sirens screamed. Medics had long since scuttled off to safety or to seek their illusion of safety in the savage streets. When the sound of the sirens finally faded, there was only the faint mechanical humming there in the vast, darkened room. after an interval, it ceased the oxygen inputs, and the waste cycle attachments no longer functioned. Now only the stereo system continued to pour soothing sound into the compartments housing each individual infant. To the crooning accompaniment of a lullaby the baby’s turned blue and died…”

Is Sneak Preview a masterpiece? I kinda think it is. You’ll never see a SF Masterworks edition, and this novel appears to be lost to time. The shifting tone is part of the power, the humor makes it a fun read, and the strange out-of-joint feeling makes it seem impossible. When you read Foundation, it makes sense that you can understand where it came from. Sneak Preview, makes sense if you understand Bloch, but if you think of him as the author of Psycho, maybe not. This novel deserves a few more eyeballs and memory devoted to it.

Editor’s note: You can find Sneak Preview in Amazing Stories here on the Internet Archive.

David Agranoff Grew up in Bloomington, Indiana hanging in the park that inspired this novel. His future wife worked at the Spoon serving the real-life Electric Fred. They have two of his notebooks and a house full of rescued animals. David is a novelist, screenwriter and a Horror and Science Fiction critic. He is the Splatterpunk and Wonderland book award nominated author of 11 books including the novels the WW II Vampire novel – The Last Night to Kill Nazis, and the science fiction novel Goddamn Killing Machines from CLASH BOOKS, The Cli-fi novel Ring of Fire, Punk Rock Ghost Story He co-wrote a novel Nightmare City (with Anthony Trevino) that he likes to pitch as The Wire if Clive Barker and Philip K Dick were on the writing staff. As a critic he has written more than a thousand book reviews on his blog Postcards from a Dying World which has recently become a podcast, featuring interviews with award-winning and bestselling authors such Stephen Graham Jones, Paul Tremblay, Alma Katsu and Josh Malerman. For the last five years David has co-hosted the Dickheads podcast, a deep-dive into the work of Philip K. Dick reviewing his novels in publication order as well as the history of Science Fiction. David’s non-fiction essays have appeared on Tor.com, NeoText and Cemetery Dance. He just finished writing a book, Unfinished PKD on the unpublished fragments and outlines of Philip K. Dick. He lives in San Diego where you can find him hooping in pick-up games and taking too many threes.