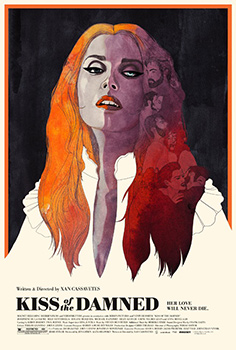

Kiss of the Damned

written & directed by Xan Cassavetes

starring Milo Ventimiglia, Joséphine de La Baume, and Roxane Mesquida

2012

Streaming: Netflix

Rental: iTunes

Purchase: Amazon

Kiss of the Vampire, Xan Cassavetes’ vampire romance, wallows in the two aesthetics common to gothic, European decadence: beauty and boredom. And while Kiss of the Vampire succeeds on the first count-—it is undoubtedly beautiful in many scenes—the boredom is overwhelming. Instead of being something that the characters feel and the audience observes, it suffuses the viewer, too, thanks to the film’s flimsy characters and directionless plot.

In this Twilight era, “vampire romance” is as much epithet as description, but the subgenre has a venerable history stretching back through Buffy and Angel and Bram Stoker’s Dracula to Jean Rollin’s softcore Eurotrash films of the 60s and 70s and Sheridan le Fanu’s 1872 novella Carmilla. While Kiss of the Vampire may call Rollin’s work to mind, with its static setting and odd motivations, it reminded me more of Harry Kumel’s bizarre, wonderful Daughters of Darkness.

As with most vampire romances, Kiss of the Damned centers on an overwhelming, all-consuming attraction. Anemic vampire Juno chances across screenwriter Paolo in a video store (!!) and when their eyes lock, their destinies intertwine. After a few practically wordless tete-a-tetes, their bond is cemented. Exactly what adhesive keeps them together is unclear based on what’s onscreen: Is Paolo under a supernatural thrall? Does he just really like her? What does she see in him (besides Milo Ventimiglia’s obvious charms)? We never understand what draws them together so strongly.

Depsite being a vampire, Juno is not your average bloodsucker. She avoids human blood and sends Paolo away after make out-spawned vision of his blood streaming down her chin unsettles her. Paolo believes—conveniently, with little proof—Juno’s claim that she’s a vampire and somehow isn’t frightened by it (with good reason, as it turns out: there’s practically nothing in the film that makes being a vampire seem bad). They feign attempts at self control, but after an inventively staged scene of them making out through a cracked-open, but locked, door, they have sex. (spoilers ahead) For a moment, it seems that Paolo’s love and faith (and broodiness and biceps) have conquered Juno’s vampirism, but soon enough she’s biting him and he’s a vampire. When Juno asks him whether he’s frightened by his transformation, Paolo replies: “No. This is what had to happen.”

Which, like the pair’s attraction in the first place, is puzzling. We know almost nothing about him. He’s a screenwriter, renting a house away from the city while he works on a new script. Maybe this change did need to happen, maybe not, but the audience has no way of discerning that because nothing has been presented to help us understand one way or the other. And that’s the problem with Kiss of the Damned: it hits all the marks you’d expects, but earns none of them. The audience is carried from point A to B to C, but why are we making the journey?

Thing are shaken up by the appearance of Juno’s inevitably wild and dangerous younger sister, Mini, a vampire less interested in being genteel and debating whether they themselves are monsters (as Juno and her friends do at a dinner party; for philosophizing vampires, I prefer The Addiction) and more interested in having a good time. Mimi threatens many things, but when the end comes, neither Paolo nor Juno have anything to do with stopping her. They’re observers in their own story.

There are things to like about Kiss of the Damned, though they’re all aesthetic. There are some beautiful, arresting shots crafted by Cassavetes and cinematographer Tobias Datum, especially in the contemplative opening montage. Unlike much modern horror, the film’s color palette is appealingly warm. Forget the cool blue filters; much is yellow and orange, giving a rich, almost fatty, decadence and heat to the proceedings.

Kiss of the Damned gives off the vibe of an American independent film mixed with decadent 70s Euro-horror. Perhaps this isn’t surprising given that Cassavetes is the daughter of indie legend John Cassavetes (best known to horror fans as Guy Woodhouse in Rosemary’s Baby). But it lacks what the best of those films have: a strong emphasis on character. Many such films grow out of, and succeed due to, their strong, closely observed characters. By making Paolo, Juno, and Mimi stock figures from central Transylvanian casting, Cassavetes leaves her audience sharing too keenly the emptiness of her characters’ lives.