Space travel may some day be within the realm of the daredevil, the reckless young, the average kid. Some may reach for the unattainable, or what we might call the impossible. Set a record, or die in the attempt. What we do, rein them in, or encourage them?

Pablo Grace sat alone, studying a chess board at a small, circular wrought iron table in the brightly lit courtyard, with stone pavers and leafy trees filtering the afternoon sunlight.

He moved his white bishop. Check. The opposing King moved on its own, away from the attacking bishop. Adrian wondered whether the opponent was remote or just a gamebot. Probably a gamebot. Augment connections cost credits, and rogue enclaves were cash poor places.

“Pablo?” Adrian asked.

The young man looked up.

“Adrian Arroyo,” Pablo said. “Finally tracked me down, eh?”

“Were you expecting me?” Adrian asked.

“Clayton man comes up into the hills askin’ questions,” Pablo said. “People start to talk.”

Adrian bristled. “I’m not a Clayton man,” Adrian said.

“Clayton your patron?” Pablo asked.

“It’s not like that,” Adrian said. “I teach propulsion theory at the Naval Academy. I’ve lived here for a long time.”

“You don’t live here, Clayton,” Pablo said.

“I’m from Lancaster,” Adrian said. “Clayton sponsors me, and funds my work, but I’m not just some hired thug.”

“You better than all the lowly thugs, yeah?” Pablo said.

“I didn’t say that,” Adrian said, frowning.

Pablo smiled without any genuine cheer. He waited for Adrian to explain himself, to defend his careless remark. Pablo knew that he had the upper hand for the moment, but like anyone living on the fringes of society, he also knew that his advantage wouldn’t last very long. Rogues weren’t protected by any patron.

Adrian decided, reminded himself, that he didn’t care if this young rogue liked him or not. He didn’t want to be here in the first place, chasing after Sebastian Porter’s wayward granddaughter, but he didn’t have much choice, because Sebastian Porter had donated a large sum of money to the Academy and had advocated for Adrian’s patronage to Clayton. He’d served on the Clayton board of directors for a very long time — in fact, he and Oscar Clayton’s father had founded the company back at the turn of the century. Sebastian Porter was one of the original lions of space commerce, following in the footsteps of the old gods — the men and women of the 20th and 21st centuries, who blasted off into space strapped inside tin cans, sitting on top of exploding liquid nitrogen and oxygen — then found a way to make money doing it.

Porter’s granddaughter was one of Adrian’s best students. Brilliant, and born to fly, piloting cargo skiffs to Clayton’s Plato Crater facilities on the moon since she was sixteen. Now at nineteen, she was finishing her PhD. But now, she was missing.

“Where’s Dana Porter?” Adrian asked. “She’s been flying out of every spaceport in Lancaster for the last few months for no reason. Pleasure trips, different flight crews every time. Ten, maybe twenty orbits. Never quite enough to raise any flags, but she’s up to something.”

“Don’t know,” Pablo said, returning to his game.

“Yes, you do,” Adrian said. “She’s been flying out of every spaceport in Lancaster for the last month for no reason. Orbital pleasure trips, different flight crews every time. Twenty, maybe thirty orbits. Never quite enough to warrant filing an orbital flight plan. Staying off the radar. But she’s up to something.”

“So maybe ask her,” Pablo said, returning to his game.

“You showed up four times in the composite augment feeds,” Adrian said. “Two million people in Lancaster. Nine spaceports. But you keep showing up in the feeds, fueling her cutter.”

“Can’t help you, boss,” Pablo said.

“Try harder,” Adrian said. “She flies the Cordelia.”

“Is a crime to fuel loyals down in the city?” Pablo asked. “I fuel lotta’ loyals. That’s what I do, Clayton. Is what I do.”

“The Cordelia came off the line last year with a brand new thorium engine,” Adrian said. “State of the art fissile reactor. You selling thorium mix now? Because that would be a crime.”

“Alpha tetra hex for the plasma,” Pablo said defensively.

“Why would Dana let rogues tear apart her brand new ship and retrofit that gorgeous thorium engine with an old tetra hex piece of junk and a fluorine oxidizer?” Adrian asked.

“Dash come to us, Clayton,” Pablo admitted.

“Dash,” Adrian repeated. “That what you call her?”

“She come to us on her own,” Pablo said.

“But she didn’t come to you, did she, Pablo?” Adrian asked. “She came to the druid who mixes the fuel you sell to her, isn’t that right? The druid who tore apart the Cordelia and fitted her with a fifty-year-old tetra hex engine. Give me a name, Pablo.”

“Dash tore up her own ship,” Pablo insisted. “Makes her own mix. Dash smart for a Clayton, she is.”

“You’ve been dealing tetra hex for years,” Adrian said. “You work for a druid who mixes it for you.”

“You see that on your augment feed, too?” Pablo asked.

“No,” Adrian admitted. “But for the last six months, you’ve been accepting deuterium as payment for tetra hex. And trading for time at a lithium refinery. Why? Why would your druid need access to tritium breeder blankets? You making helium three? You got a fusion engine design tucked up your sleeve, Pablo?”

“What if I do?” Pablo asked.

Adrian laughed.

“You don’t even realize how crazy that sounds,” Adrian said. “I don’t know yet what your druid is up to, Pablo, but I’d bet credits it’s not fusion. And I’m running out of patience.

You seem like a smart kid, but you’re not that smart.”

“I’m not a druid because you say so?” Pablo asked.

“That’s right, Pablo,” Adrian said. “You’re not a druid. But that’s actually good for you, because I don’t like druids. They’re reckless. They know just enough to be dangerous. They’ll throw together whatever crazy mix of molecules hasn’t been tried yet, and then light it up to see if it burns. To see if they can finally turn lead into gold. That’s not science.”

“Rogues not allowed to learn any science,” Pablo said. “No patron, no learning. Our druids learn what they can. Teach what they can. Learn and listen, that’s all we got.”

“It’s random,” Adrian said. “It’s dangerous.”

“It’s all we got,” Pablo said.

“Give me the name of the druid you work for,” Adrian said.

Pablo sat silently.

“I just want to talk to him,” Adrian said.

“Dash is gone,” Pablo said.

“What do you mean?” Adrian asked.

“She’s eleven up,” Pablo said.

“Another pleasure trip?” Adrian asked.

Pablo moved his white bishop again.

“Where is she scheduled to land?” Adrian asked impatiently.

“Dash is making a run,” Pablo said.

“A run?” Adrian asked blankly.

“The Mars race,” Pablo said.

Adrian exhaled. Blinked. Opposition Run.

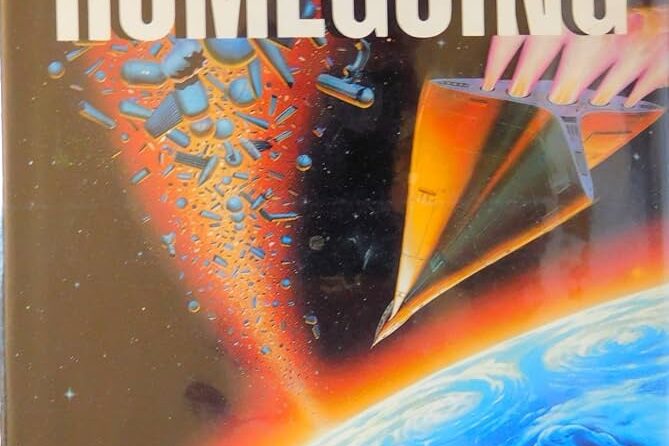

The hair stood up on the back of his neck. Opposition Run was an illegal space race to Mars and back. Every two years or so, when Mars and Earth were at their closest point, dozens of racers all over the world would load up small skiffs and cutters and pleasure yachts with extra fuel, water, and oxygen, to try their luck executing a slingshot maneuver around the red planet, hopefully catching up with the Earth on the return flight before it slips too far away.

Earth moves faster than Mars around the sun, so the key to a successful run meant anticipating your top speed and timing your flight so you don’t end up chasing Earth for weeks on the trip back home. A decent ship could reach Mars at opposition in less than thirty days. If she picked up enough extra velocity on the slingshot, she could make it back to a high Earth orbit in less than two months. The best time ever posted was fifty-five days. Pavel Petrovich took off from Siberia and landed somewhere down in South America near the equator. Had to hike three days out of the jungle because the emergency location beacon on his ship wouldn’t light up. That was seven years ago.

Of course, the distance between the two planets varied a great deal, depending on how close Mars was to perihelion. Seven years ago was a good year. Total distance that year had only been fifty-nine million klicks. Petrovich tried the run again two years ago, but waited too long, and ended up chasing the Earth for eighty days with only two months of life support. Autopilot put him into a stable Earth orbit after a hundred twelve days in space, but he’d been dead for more than a month by then. That’s why the race was illegal.

“Why would she?” Adrian asked. Not asking Pablo really, just giving voice to his thoughts. “It doesn’t make any sense.”

Pablo took it the wrong way.

“Sure, Clayton,” Pablo said. “Why would Dash rub up against us dirty rogue folk, eh? Risk everything to make a run, with a dirty rogue crew and a dirty rogue tetra hex engine? Crazy, eh?”

“Give me a name, Pablo,” Adrian said.

“No,” Pablo said.

Adrian reached for his terminal and swiped a holographic feed into the space between them. An image flickered. A teenage girl sitting on a bunk in a small, sparsely furnished room.

“Her name is Corin, right?” Adrian asked. “She’s your cousin? And she’s not supposed to be here, is she, Pablo?”

Bartek was pruning a pear tree. He stopped and smiled when Pablo and Adrian approached. The compound was surrounded by a thick stone wall. Pablo had punched a code into the panel near the gate door, and then the door had buzzed and opened. Adrian wasn’t sure what to expect, but he certainly didn’t expect a balding, elderly fellow with bright eyes and a bright smile.

Bartek seemed genuinely pleased to see them both. It was almost as if he’d been expecting them. He twisted the nozzle on the drip line near the base of the pear tree he’d been pruning, and when he was satisfied with the flow, he gathered up the cut branches and turned to face them both. Pablo was still afraid because of Corin. Adrian could tell looking at Bartek that the older man knew somehow. Knew that something was wrong at least. Bartek still smiled, but his smile was shaded by concern.

“This is the teacher?” Bartek asked.

Pablo nodded.

“Is everything all right, Pablo?” Bartek asked.

Pablo said nothing. His mouth was a tight line of worry.

“You’ll check in from time to time?” Bartek asked.

“Is okay to go?” Pablo asked.

Bartek looked at Adrian, asking the question.

“Of course,” Adrian said. “She’ll be safe now. Go home.”

Pablo returned the way they’d come. Bartek waited, smiling as he watched Pablo leave. He waited until Pablo had reached the thick stone wall, and then moved beyond the gate door and closed it behind himself, locking them inside.

“I assume you’ll be staying for a while?” Bartek asked.

“Has Dana initiated her first burn?” Adrian asked abruptly.

“Oh my, no, not yet,” Bartek said. “Tomorrow.”

“Mars opposition is in fifteen days,” Adrian said.

“Three hundred sixty-seven hours,” Bartek said. “But yes, essentially, you are correct. Opposition in fifteen days.”

“She’s too late. She’s going to miss,” Adrian said.

“I don’t agree,” Bartek said.

“Tell me she has enough life support,” Adrian said.

“She has enough life support for fifty days,” Bartek said.

Adrian could feel his heart beginning to race. Panic and anger gripped at his chest like a wild animal was attacking him.

“Are you crazy?” Adrian shouted. “What’s the run this year? Sixty-five million klicks? Sixty-nine? Even if she beats every metric by a country mile, she’s going to be drinking her own piss and breathing through shredded carbon scrubbers by the time she lands. And that’s if she doesn’t miss!”

“Dana is perfectly aware——“

“Get her on comms,” Adrian interrupted angrily.

Bartek stood very still for a long moment. His smile had vanished, but he didn’t seem to be angry. He looked like a man who might have been choosing his words carefully, but in the end, he chose not to say anything at all. He turned and moved toward the small adobe house at the center of the compound. He dropped the pruned branches into a composting container near the back of the house, then entered through the back door. He hadn’t invited Adrian to join him, but Adrian followed anyway.

The house was simple and clean. The holographic display in the center of the living area was an older design. The kitchen and dining areas were unremarkable. Bartek moved deliberately through the dining area to a floating staircase at the back that led up to the second level. Adrian followed.

Upstairs, a narrow hallway led past sleeping quarters on the right, and then into a large office with large windows. Bartek entered the office and touched a panel on the wall that clouded the window panes, diffusing the light that streamed inside, then moved to his desk and activated his work station, unlocking the interface and opening a holographic map of the Earth.

The orbiting Cordelia was indicated on the map by a blue icon marked with the name of the ship and a column of telemetry data—mass, position, vector, exhaust velocity, fuel capacity, life support, and duration of flight.

Bartek seemed content to study the map telemetry, so Adrian impatiently opened a communication terminal. A moment later, he’d hailed the Cordelia, and Dana’s face filled the terminal display panel. Dana didn’t look happy, however.

“What the hell,” Dana said.

“Your teacher has paid us a visit,” Bartek said.

“Damn,” Dana said. “That didn’t take long.”

Teacher.

That was the second time Bartek had called him a teacher.

“I’m her advisor,” Adrian said. “She’s working on her doctoral thesis, and I’m head of the whole damn department.”

“No offense was intended, I assure you,” Bartek said.

“I’m still sixteen hours out,” Dana said.

“We can calculate a new solution,” Bartek said.

“I want you to come home, Dana,” Adrian said.

“Not gonna happen, Adrian,” Dana said.

“Why are you doing this?” Adrian asked. “You’re not some unknown kid from the Territories. The world already knows you.”

“So?” Dana asked.

“You’re not the kind of pilot that needs to make a run.”

“What kind of pilot am I?” Dana asked.

“Put her down, Dana,” Adrian said.

“I can’t,” Dana said.

“Don’t make me take flight away from you,” Adrian said.

“We assumed that the elder Mr. Porter would have given you the flight control codes for the Cordelia,” Bartek said. “We’ve planned accordingly, I’m afraid.”

Bartek touched and swiped at the interface. The holomap expanded to include Mars, and a projected flight path emerged between the Cordelia and the red planet. Bartek gestured again, and the data consolidated itself into a comm package. Bartek swiped once more, and the package was sent.

“I’ve got the new solution,” Dana said. “It adds six hours. And you’re asking nine percent more out of the engines.”

“They can handle that,” Bartek said.

“Dana, I’m serious,” Adrian said. “Stand down.”

“I’m green across the board for a DTH3 burn,” Dana said.

“You’re not going to make it!” Adrian shouted.

“Execute the new vector first,” Bartek said.

“Copy that,” Dana said.

“Stop!” Adrian said. “Now!”

“Executing vector,” Dana said, ignoring Adrian’s outburst.

The telemetry column next to the ship’s icon displayed the new coordinates, and the projected flight path changed a bit to reflect the new position and vector of the Cordelia as it burned away from the planet and set off on its rendezvous with Mars.

“That’s it,” Adrian said. “I’m taking control.”

“Your vector is splendid, Dash,” Bartek said. “Go for DTH3.”

“Engaging,” Dana said. “Sorry, Adrian.”

Adrian began to enter the command codes for the Cordelia but before he could finish, the failsafe locked him out. Adrian stared at the alert, blinking stupidly back at him. This has to be wrong, he thought. He tried again. Failed again.

Failsafes were built into every spacecraft capable of high orbit because at too great a distance, it didn’t make sense to allow for remote navigation, given the amount of time it would take for a remote signal to traverse the distance. But the Cordelia had been well within the upper bounds when he’d begun entering the codes.

“What just happened?” Adrian asked.

Interference began to scatter Dana’s image on the comm panel and Bartek was quiet. Adrian answered his own question by reading the telemetry. He just couldn’t believe it was true.

The Cordelia had executed a burn that put her on course to reach Mars at the moment of opposition, but she’d already waited longer than any racer would have dared. Ideally, if you burn early and reach Mars before true opposition, you give yourself a better chance of catching the Earth on the way back.

The solution Bartek sent Dana assumed an exhaust velocity that was impossible. And yet, the Cordelia’s telemetry suggested that she was on track to satisfy the plot. He watched her speed increase rapidly as she burned. She was flying faster than any spacecraft had ever flown, far faster than even the experimental ships that Clayton was secretly developing for the Navy. Adrian did some quick calculations in his head.

“A hundred forty thousand at the turn,” Adrian said.

“That’s very close,” Bartek said. “I expect her to reach one hundred forty four thousand eight hundred forty kilometers per hour by the time she reaches Mars.”

“That’s not physically possible,” Adrian said.

“May I take that as a compliment?” Bartek asked.

The sleeping quarters they’d passed in the hallway were actually guest accommodations. Adrian was allowed to stay in that room. It was comfortable and clean, and his window looked out onto a wide courtyard. Clean clothes that fit him had been stacked neatly in the chest of drawers beside the bed, and the washroom had fresh towels and a new toothbrush and razor. Bartek retired every evening to a set of rooms behind a narrow door at the back of his office. Adrian never saw those rooms.

Once the Cordelia was well and truly beyond his reach, Adrian had immediately begun peppering Bartek with questions. He guessed that DTH3 meant fusion, and Pablo had admitted dealing in deuterium and helium three, but fusion engines were still far beyond the reach of the finest scientific minds on the planet, so how could a rogue druid have mastered the impossible bounds and complexities of a fusion engine design? Did the conventional fissile materials trigger the fusion reaction? And how would you isolate the heat? An electromagnetic field? How do you create a field that strong? And what kind of materials could withstand the residual heat from such close proximity isolation? And what about plasma ejection at those elevated temperatures? What could possibly insulate the nozzles that efficiently?

Bartek deflected most of Adrian’s questions. After several days, Adrian began to calm down a bit. He spent most of his time in the office watching Dana’s progress at Bartek’s work station, which served as flight control for the Cordelia. Bartek would sometimes work in the orchard, leaving Adrian alone and on his own. The first few times, Adrian barely noticed that Bartek was no longer with him, such was his focus on the Cordelia. But once he had noticed, and was sure that Bartek would likely be gone for several hours, Adrian began searching for answers.

Bartek wrote most of his original notes on actual paper, and had stacks of it piled high on tables and chairs all over the office. Adrian probably glanced at every page, and read most of the material he thought might be important. He understood most of what he read at first glance, but when Adrian didn’t understand a particular sheaf of equations, he’d stop and study them until he did. And sometimes afterwards, he still didn’t understand where Bartek was headed until perhaps hours or days later when Adrian would find another few pages, and then suddenly he’d see it, as if a light had been switched on. Yes, of course, that’s where the old man was going.

Then Adrian would feel a surge of wild excitement, as if he’d discovered a treasure chest filled with gold in the attic. But he’d also feel a deeper, quieter shame at not having grasped the idea, whatever it was, until Bartek’s papers had proved to him that such a thing was possible.

As the days unfolded, Adrian found himself worrying less and less about the run, although he did continue his vigil at the flight control work station, waiting for a log entry from Dana.

On the seventh day of the flight, the comms chirped. Bartek was standing near the window. Adrian was seated behind the desk. Bartek nodded, so Adrian swiped at the comm terminal. Dana’s face filled the translucent display hovering above the desk.

Flight, this is the Cordelia. Local frame flight time is one hundred seventy-two hours, six minutes, seventeen seconds. I’m about thirty-five million klicks from home, so in just under two minutes, I guess… y’all should be getting this.

Fusion reactor is stable, and containment is green across the boards. I’m tempted to open her up just to see what she can do, but if I did, I’d probably stroke out on the slingshot. Plus, there’s a rattle somewhere in the aft storage compartment, and I can’t get back there under thrust to figure out what’s going on. I’ll check it out once I’ve made the turn.

Hope you boys have been getting along. Sorry I wasn’t up front with you, Adrian. But you would have stopped me, and I didn’t want to be stopped. It’s better this way. Don’t be mad at Bartek, okay? It was all my idea. All me.

The log entry ended. Adrian dismissed the display panel.

“She’s going to be alright,” Bartek said.

“So far so good, I guess,” Adrian agreed.

Bartek came and sat down next to Adrian.

“Tell me about yourself,” Bartek said.

“I’m a scientist,” Adrian said. “I have PhDs in aerospace propulsion and astrochemistry. I teach at the Naval Academy.”

“And your research?” Bartek asked.

“I don’t publish as often as I used to,” Adrian admitted. “I have responsibilities to my department——“

Bartek waved his hand in the air, dismissing the thought. Then he shifted his chair to face Adrian directly, and looked at him. And only then did Adrian realize that Bartek had never done that before. Never once since Adrian had come to the compound had Bartek ever looked directly at him, with focus and intent. And he did so now deliberately, the way a botanist might look at a rare specimen of flora.

“You are a creature of the edifice,” Bartek said.

“I don’t think that’s fair,” Adrian said.

“I don’t mean that in a disparaging way,” Bartek said.

“I’ve slowed down,” Adrian said. “I admit that. Young minds are more fertile. I’ve planted my flag, and now I’m helping the next generation move scientific understanding further.”

“And even as they venerate you, they also gently insist that soon you must go and find a quiet place and tend a garden.”

Adrian felt a sharp pain in his abdomen. Of course, Bartek was correct, but Adrian had spent years creating a barrier in his mind designed to deflect that notion, insisting instead that he was an integral part of the system. A cog in the machine, one might argue, but an important cog, without which the machine would break down. Yes, of course, he’d slowed down. Everyone did at some point in their career.

And yet now, he’d encountered a druid who’d managed to keep going. Bartek hadn’t slowed down at all. His ideas were often intuitive rather than methodical. His experiments weren’t always rigorous, but there was a method to his madness, and his results were unassailable.

“How do you…” Adrian began. “How do you do what you do?”

“I’ve never been a creature of the edifice,” Bartek said. “I’ve never been told that I’d achieved anything, so I never stopped searching for answers. And at some point, I began to understand that searching for answers is what I enjoy most.”

“I’m tired,” Adrian said. And he was. Sebastian Porter wanted him to find Dana and tuck her neatly back into the hole that Clayton and the Academy had carved out for her. But there was a part of him that just wanted to go away, to give up his place, to make room for the next deserving cog in the edifice, to go and find a quiet place and tend a garden.

Adrian looked at the holomap, at the Cordelia icon, and thought about Dana hurtling through the void. The edifice was just an elaborate illusion, he thought. We’re all just hurtling through the void.

After that day, Adrian began spending less time in the office. Often, he would visit the courtyard below his window. A garden had been planted there, and Adrian would sit on a bench in the shade for hours, looking at the plants and the small creatures who lived among them and depended upon them. Twice, he joined Bartek out in the orchard, tending the pear trees and the apple trees. Adrian could feel himself starting to relax.

He didn’t neglect the Cordelia, however. He checked flight control several times a day, and on the fifteenth day of Dana’s run, after he and Bartek had both retired to the office late in the afternoon, they found a new log entry waiting for them.

Flight, this is Cordelia. Local frame flight time is three hundred sixty-eight hours, forty-two minutes, three seconds. I’m four minutes out from you now, preparing for the turn. When you get this, I’ll be about thirty seconds from the well, hitting a max speed under pure thrust of nearly .012c. That’ll work out to about a nine-g slingshot, which I’m pretty sure I can handle.

I can see the northern colony lights on the dark side of the planet. Can’t help but wonder if those folks know I’m up here making a run. I’ve gotta be the last racer, lighting up so close to opposition. Anybody down there tracking me must think I’m on a one-way trip. Supply ship or a shuttle. It’s pretty, the lights. Northern hemisphere is quiet. I can see a couple storms down south, but they look small. Gonna be a nice evening down there on Mars. I think I’d like to visit someday.

I’m in pretty good shape for the turn. Only thing bothering me is that rattle. The fusion bottle is solid, but the mag field vibrations are stressing the hull and some of the bulkheads. I think there might be a weak weld back there somewhere. Couldn’t get to it under thrust, but after the turn, I’ll be able to dig around until I find it. Okay, boys, I’m switching over to the LaGrange relays now so you don’t lose me on the map.

The holomap displayed the location of the Cordelia as of four minutes ago when the telemetry signal left the ship, as well as a calculated projection of her actual position at that current moment, assuming she was still on course and nothing had gone wrong in the last four minutes. The projected Cordelia was less than a minute from reaching the slingshot altitude that would turn the ship back toward Earth. Just before she reached the gravity well, Dana would throttle down for the duration of the turn, and then fly ballistic for four days. After that, she’d spin up the Stagmer Sphere to orient the ship with the engines aimed toward the Earth. Then she’d fire up the DTH3 bottle again, and begin the long deceleration that would bring her home.

Adrian and Bartek waited silently until the projection indicated that the Cordelia had reached Mars. There was really no reason to wait and watch, but Adrian and Bartek waited and watched anyway.

They imagined the Cordelia approaching the gravity well of the planet and then beginning her turn. In four minutes, they’d receive confirmation, but it was comforting to stand in front of the holomap and watch the slightly lighter blue icon, the one that represented the Cordelia’s projected position, and imagine it all happening. In twelve minutes, if everything went according to plan, Dana would fire thrusters that would gently nudge her ship away from the embrace of Mars and put her on a course that would bring her back to the Earth.

Four minutes into the turn, actual data began arriving and an alarm immediately sounded. Adrian felt his focus narrow. His thinking grew sharp and cold. Military training took over as he scanned the incoming telemetry for indicators. A thermal anomaly in the aft section. Not the reactor, since she’d already cut the engines. But something bad had happened back there. The ship was spinning, but it was a slow spin and it looked like the Stagmer Sphere was already reorienting the ship.

Nothing had exploded. An explosion would have caused a much more violent spin. Dana would have stroked before the sphere had had a chance to negate the spin. Of course, all this had happened four minutes ago. So what exactly had happened?

Oxygen levels had dropped by forty percent. Adrian touched the map, expanding the Cordelia icon to a full schematic of the ship. Three oxygen tanks had been added to the aft hull plates. The rattle Dana had heard must have been one of the new welds, just as she’d suspected, and the added force of the turn must have torn one of the tanks off the ship. Goddamn rogues, still welding their own joins without any robotics. Goddamn rogues.

“She’s only got seven days of air,” Adrian said. His fingers flew across the hovering interface as he calculated an adjusted flight plan. “If she can reach a max velocity of .0173c within four days, then she can turn and burn here…” He touched a spot on the proposed vector. “It’ll be a hard decel, but it won’t kill her, and she’ll make it back in time. Barely.”

“She’ll have to start the fusion reaction the moment she finishes the turn,” Bartek said.

“And she’ll have to burn nineteen percent hotter than she did on the way out,” Adrian said. “Can your engine handle that?”

Bartek nodded, so Adrian began wrapping up his calculations into one consolidated comm package, and then passed it to Bartek.

“Perhaps you should send it,” Bartek said.

“Go ahead,” Adrian said. “She trusts you.”

Bartek touched the interface and the message was sent.

Supplemental log. Local frame flight time is three hundred sixty-nine hours, three minutes, seventeen seconds. So yeah, I got your message. Thanks for the assist. The fusion bottle is hot, and my speed is increasing. Looks like I’ll make maybe .016c in about seventy-six hours. That’s gonna have to be good enough. Scrubbers will keep me alive for a while once the tanks are all empty, and I’ll be local then, so if I pass out, you can use those command codes my grandfather gave you to bring me in.

Don’t blame Bartek for any of this, Adrian. I pestered him for a year before he agreed to let me see his designs. I’d found some of his early papers in my grandfather’s files—Bartek had applied to Clayton for sponsorship when he was young. He showed my grandfather all this really promising work, but my grandfather didn’t want a self-taught rogue druid showing up the graduates of his precious Academy, so he turned Bartek away. Buried his ideas. Druids only want to turn lead into gold, he’d always say. You’ve heard him say it. Hell, I’ve heard you say it.

But now, you’ve read his notes. You’ve seen his engine fly. Adrian, Bartek finished this design nine years ago. If Clayton had been behind him this whole time, we’d be headed to Tau Ceti by now. Do you understand now, why I made the run? Don’t let my grandfather bury this. I mean, if I don’t make it back. Please, Adrian. Tell everyone about this. Tell them the truth.

Adrian held the edge of the desk to steady himself. He felt dizzy and disoriented, and a part of him understood it, and also marveled at how much he’d depended upon that which Bartek had called the edifice, now that its foundations were crumbling beneath him. He’d believed that the edifice was something pure and noble, a cathedral dedicated to the pursuit of truth. His head swam as he considered his life’s work—chasing praise and earning accolades, honors, and certificates—while up in these hills, Bartek had toiled year after year, chasing the mysteries of the universe, forging ahead to places beyond the edges of all the maps, unlocking doors and throwing them open for the sheer thrill of having done it.

“She’ll make it back,” Bartek said.

“Yes,” Adrian agreed, numb. “Yes, of course she will.”

Bartek began chuckling. Adrian looked at him, suddenly wanting to know why. Bartek stopped, and softened his smile.

“Lead into gold?” Bartek asked. “Is that what you folks thought I was doing up here? Trying to turn lead into gold?”

Adrian felt his cheeks warm with shame, and he turned away.

“Isaac Newton was an alchemist,” Bartek said.

“I know,” Adrian said. “I never—I mean, I’m sorry…”

“Please,” Bartek said. “There is no need for that.”

“I’m going to make this right,” Adrian said. “I’ll speak to Sebastian Porter, to the administrators at the Naval Academy—“

“No, you mustn’t,” Bartek said.

“Why not?” Adrian said.

“Dash and I made a deal,” Bartek said. “I only agreed to let her fly my little engine because she promised to keep me out of the spotlight. I don’t want everyone trampling all over my orchards, bothering me with useless questions about work that I’ve already finished. I’m happy with my life, just as it is. And I’ve got more work to do. Surely, you understand that.”

“No, I don’t,” Adrian said.

“I’m not a creature of your edifice,” Bartek said.

Adrian stopped. Again, his head swam. He was still incapable of contemplating the world, except through a transactional lens. Barely a moment ago, he’d experienced an epiphany that had shook him to his core, and now he found himself already trying to drag Bartek back through the hard won breach, back to the wrong side.

“Yes, of course,” Adrian said. “Bartek, I’m so sorry.”

And he was. He’d recognized his ignorance at last, and with that recognition came a desperate need to stay, to rely on this strange man, this rogue druid, for guidance and example. Adrian decided that he wanted to follow Bartek wherever the old druid might lead him, knowing that his own happiness would be improved immeasurably for having done so.

Adrian let silence amplify his acquiescence for several long moments. Bartek encouraged the silence, happy, comfortable in the midst of it.

“What made you laugh?” Adrian asked finally.

“When I was a young man,” Bartek explained, “I developed an experiment that accelerated neon-20 to .97c, and collided it into a carbon nanotube surrounding a stack of lead-208 atoms. It was a lovely experiment, very elegant, and it neatly knocked several protons and neutrons off of each lead atom. Three protons, quite often. So of course, eighty-two protons, less three…”

Adrian laughed.

“You turned lead into gold.”

For Immediate Release. Lancaster, Mojave, Western States Alliance. February 17, 2168. Dana Porter, a PhD candidate at the Naval Academy in Lancaster, completed the Mars Opposition Run last Thursday in a record shattering twenty-two days. The race is a notorious, unsanctioned journey around Mars and back to Earth during opposition of the two planets.

Porter bested the previous record by thirty-three days in a year when Mars was nowhere near perihelion.

The ship piloted by Porter was powered by a radical new fusion design, a prototype developed by Adrian Arroyo for the Clayton Corporation. Arroyo is director of the Naval Academy’s Aerospace Engineering and Energy Sciences department, but said he would be taking an indefinite leave of absence to head up a new initiative sponsored by Clayton, to further develop what Arroyo is calling the Bartek Engine.

END