the second mission to Jupiter took place, this time comprising a Soviet mission with US passengers aboard.

I am, of course, referring to the fictional future as presented first by Stanley Kubrick and Sir Arthur C. Clarke’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey and its sequel as offered by Peter Hyams and Arthur C. Clarke, which was actually presented some 14 years following the release of the original, a bit off from the fictional timeline.

I follow a group on Facebook (2001: A Space Odyssey – The Official Facebook Group for 2001: A Space Odyssey “The Ultimate Trip”) that intensely discusses the original film, with occasional forays into the second film, the books, Kubrick, Clarke and a handful of related issues.

One fairly frequently discussed issue is whether critique and discussion should restrict itself to the film or be allowed to include related subjects, like the sequel or the books, including books that have not yet received the cinematic treatment.

The arguments both for and against widening the exclusion still continues without definitive resolution.

The other day I had a chance to re-watch 2010: The Year We Make Contact, the Peter Hyam’s directed film based on Clarke’s novel – 2010: Odyssey Two. I decided I wanted to take a look at a comparison between the two films. However, sensitive as I am to the group’s interests, I’ve chosen not to discuss fitness, or plot, or 2010’s successes or failures as a sequel. I’m not going to delve into the questions of whether or not there are contradictions between the films, nor how well or poorly the film reflects the novel. Rather, I intend to look at elements present in 2010 that seem incongruous to the setting of the original film and which, in my opinion, make it a less successful sequel than some might otherwise think.

Let me get a handful of preliminaries out of the way first.

Kubrick is generally considered to be one of the greatest filmmakers of the past century. Whether you like his films or not, you have to admit that he exhibits a great, almost obsessive devotion to detail in his films, is a master of scene composition and the combining of visuals and soundtrack/musical score. Visually, you can trace his sensibilities almost directly to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, a film that is largely regarded as one of, if not the most visually impressive films of all time.

And, at least insofar as it relates to the film in question, there is no doubt that Kubrick desired to make the film as scientifically and technologically accurate as possible. Huge dollars we spent on practical visual effects to achieve that end (such as the giant wheel constructed to emulate the rotating section of Discovery One).

Further, Kubrick deliberately chose to work with one of the most popular Science Fiction and Futurist authors of his time, namely Arthur C. Clarke who was known at that time as a practitioner of “Hard” Science Fiction, that branch of the literature that strives for scientific realism and plausibility.

Clarke had a penchant for tackling issues in his fiction that examine the relationship between science and religion, (The Star, Childhood’s End, The Nine Billion Names of God, Clarke’s Law, etc – and, in my opinion always coming down on the side of science), which is what I believe attracted Kubrick in the first place following a reading of the short story The Sentinel (of Eternity) (link is to the original publication of that story) which originally appeared in a very short-lived Pulp magazine – 10 Story Fantasy in its single 1951 issue – (whose featured story was titled Tyrant and Slave-Girl On Planet Venus, interesting company, to say the least), as their combined effort ultimately delves into to origins of humankind and (once again) posits a technological, scientifically-based explanation.

A couple of other points before moving on: Clarke wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey while the film was being made. He wrote 2010 as a novel first and it was then adapted for the film version. 2010 was not actually filmed until some 16 years following the release of 2001 and film technologies and techniques had advanced (as had technology generally – in 1968 when 2001 was released, computers were still generally perceived as room-sized monstrosities employed only by large corporations and governments. By 1982, personal PCs were on their way to becoming ubiquitous, and computer scientists (at least) were aware that the road to HAL was a lot longer than anyone had previously anticipated.

2010 isn’t a bad film, so much as it is a film that ignores Kubrick’s aesthetic approach to the property, and does so in some ways that are really questionable. When viewed back-to-back, they could be described as “jarring”.

These differences express themselves in three primary ways, through set design, sound track and characterization.

The first thing that one might notice is that, compared to 2001, 2010 is a highly emotional film. In 2001, about the only real emotions we see on display are exhibited by the man-apes during the Dawn of Man sequences.

Elsewhere, every character is presented in a dry, clinical, professional, detached manner, with two exceptions – Bowman’s facial expressions during the trip through the infinite suggest great emotional turmoil. The other scene takes place during the Moon Bus trip to TMA-1, where wonder and joy are expressed over the quality of the space rations. That scene is very pointed, seemingly a slap upside the head of the audience by Kubrick, saying “pay attention”, because it takes place on a for-gossakes Moon Bus, flying over the Moon, amongst people dressed in spacesuits while heading for a scientific anomaly that could be (and is) the greatest discovery ever made by humankind. These people are about to encounter alien technologies. Instead of talking about that, they’re discussing ham sandwiches. I think Kubrick uses this scene to demonstrate several things, not the least of which are the banality of humankind, as well as how comfortable 2001’s human beings are with technology. They’re taking it entirely for granted as they approach the manifestation of whoever or whatever GAVE them those technologies.

(This is also a call-back to the plight of the man-apes. We’re given to understand that Moon Watcher’s tribe is on the brink of starvation before the Monolith alters their consciousness. The “chicken OR ham” scene illustrates the deep, unacknowledged impact technology has had on the species. Its options prior to the advent of the Monolith were “Tapir or Nothing”.)

In contract, 2010 is all about emotion and emotional reactions; there’s Ethereal Bowman’s visits to his wife and his mother; there’s the aerobraking scene in which two of the crew huddle together in fear. There’s arguments between the crew of the Leonov, deeply emotional expressions of fear on the part of Curnow (space walk) and anger/disgust/pity on the part of Chandra (reviving HAL), news reports about the trouble in South America, Max’s excitement over taking the probe to visit the Monolith, Floyd’s home life, and more.

In contract, 2010 is all about emotion and emotional reactions; there’s Ethereal Bowman’s visits to his wife and his mother; there’s the aerobraking scene in which two of the crew huddle together in fear. There’s arguments between the crew of the Leonov, deeply emotional expressions of fear on the part of Curnow (space walk) and anger/disgust/pity on the part of Chandra (reviving HAL), news reports about the trouble in South America, Max’s excitement over taking the probe to visit the Monolith, Floyd’s home life, and more.

In 2001, we see humans presented with repressed emotions, almost with emotion excised. In 2010, we see humans giving expression to the full range of human emotion.

This is perhaps the greatest disconnect between the two films, because, unlike 2001, 2010 forces the viewer, through these emotional displays, to experience emotion, and to get distracted by them. In 2001, as an audience, we’re supposed to be concentrating on the events and their implications, on the nature of the intelligence and technology. We’re not supposed to be reacting in fear or joy, happiness or anger, because neither technology, nor science, nor the Monolith Makers care about those things – they’re not important to the story. The Monolith is going to send out its signal regardless of how people react. We’re supposed to get dragged along, through the film, regardless of our emotional reaction to it – just like humanity has been dragged through its own story by the Monolith. This connection, or, rather, this relationship between film and audience, is absolutely not maintained by the sequel.

As an audience, we are NOT supposed to become involved with the characters. If anything, our viewpoint is supposed to be that of the Monoliths/their makers. We’re the scientists staring down into a Petri dish or looking through a microscope at a single drop of water (apologies to the other Wells). In 2010, our point of view is removed from its god-like omnipresence to that of a mere, fleeting, insignificant human being. Its a terrible fall.

Sound wise, there are all manner of complaints that can be lodged. Hyams was either not concerned enough with scientific verity or caved to the presumed audience’s need to receive whooshing sounds as indicative of motion. In other words, the audience may not have been trusted enough to understand that in space, no one can hear you breathe heavily into your space helmet – unless they are inside your space helmet.

Sound wise, there are all manner of complaints that can be lodged. Hyams was either not concerned enough with scientific verity or caved to the presumed audience’s need to receive whooshing sounds as indicative of motion. In other words, the audience may not have been trusted enough to understand that in space, no one can hear you breathe heavily into your space helmet – unless they are inside your space helmet.

Here’s a bit of an explanation of how things work, so far as space and sound are concerned: In space, no one can hear you scream, because the classical music is playing too loudly.

Space is a vacuum. Sound travels as waves propagated by a medium. There is no medium in space. The only possible way to hear any sound when an individual is in space (presumably in a protected environment) is via vibration – and that would have to be a sound produced by something connected to whatever you are receiving the vibrations from. Even if you were in space in a spacesuit and a fusion motor kicked into operation a half an inch from your face, you might be blinded (put your filter visor down, dammit!), but you wouldn’t hear anything…no boom as the engines ignite, no crackle, no thunderous peals. Nothing.

Kubrick knew this – whether he had to be told by Clarke or not, he knew it and, perfectionist that he was, devoted as he was to scientific accuracy and realism, he did not allow a single sound that would not normally be heard in space to appear on the screen.

There were concerns about this voiced, I believe, by the studio. Kubrick’s use of music (Blue Danube in particular) may have just been genius on the director’s part, or it may have been a way to get past the ignorance of studio heads (and some audience members).

2010, on the other hand, does not trust its audience all that much. There are any number of whooshes, rumbles, jet sounds, and other sonic trappings, in annoying profusion (once you begin cataloging them) none of which would have been heard by the characters.

There are really only three explanations for this: Hyams was unaware of the fact that space is a vacuum (unlikely), Hyams did not possess as much dedication to realism as Kubrick (likely) or, Hyams didn’t trust his audience as much as Kubrick did (also very likely).

Here’s just a handful of instances in which we hear things that would not be hearable:

A second or two before 45:24 into the film, Discovery “whooshes” as it passes by the frame.

At about 45:51, the handheld maneuvering unit maks a “jet” sound when activated. Yes, the astronaut operating would have felt vibration, but not jet noises.

I’ll also note that the sound track during this sequence uses the breathing sounds of an astronaut to very clearly delineate whether what the audience is hearing is external or internal to the helmet, making the improper handling of the sounds we, or character, could or could not hear even more obvious.

At 49.33, we hear the hiss of an airlock door opening, when we are outside the ship.

And, in perhaps the greatest example of this problem, the Monolith (the big one in space) makes whooshing noises as it passes through the camera’s POV.

Visually, the aesthetics of the environments portrayed in 2010 also don’t track with those of 2001.

2001’s color palette is essentially a monochrome one – whites, grays, blacks. Yes, there are notable exceptions, like the red chairs in the waiting area of the space station, but these are used by Kubrick to point out the sterility of the rest of the scenes – pointedly.

The only real color we get is during the Journey to the Infinite. Even when colorful things appear in various scenes (such as when Poole and Bowman are in various locations inside the ship), those areas of color are minimized – screens displaying colored images are viewed at odd angles. Nowhere does “color” dominate a scene.

Once again, because Kubrick does not want to distract the audience from the central themes of the story.

2010 is full of color throughout. Hardly any scenes are allowed to match the monochromatic presentations of 2001. Here’s two images, one from 2001, inside Discovery, and one from the interior of the Leonov to give you some idea of how vastly different the two are:

Monochromatic and washed out colors in 2001.

Moments of color are shocking in 2001. HAL’s brain room is all red – ALL red. The Moon dock is ALL Red.

2010 has what one might refer to as a “normal” color palette. Hint: “Space” is not “normal”.

Not to mention that the color palette of more than three quarters of the film gives the psychedelic trip through the wormhole all that much more impact.

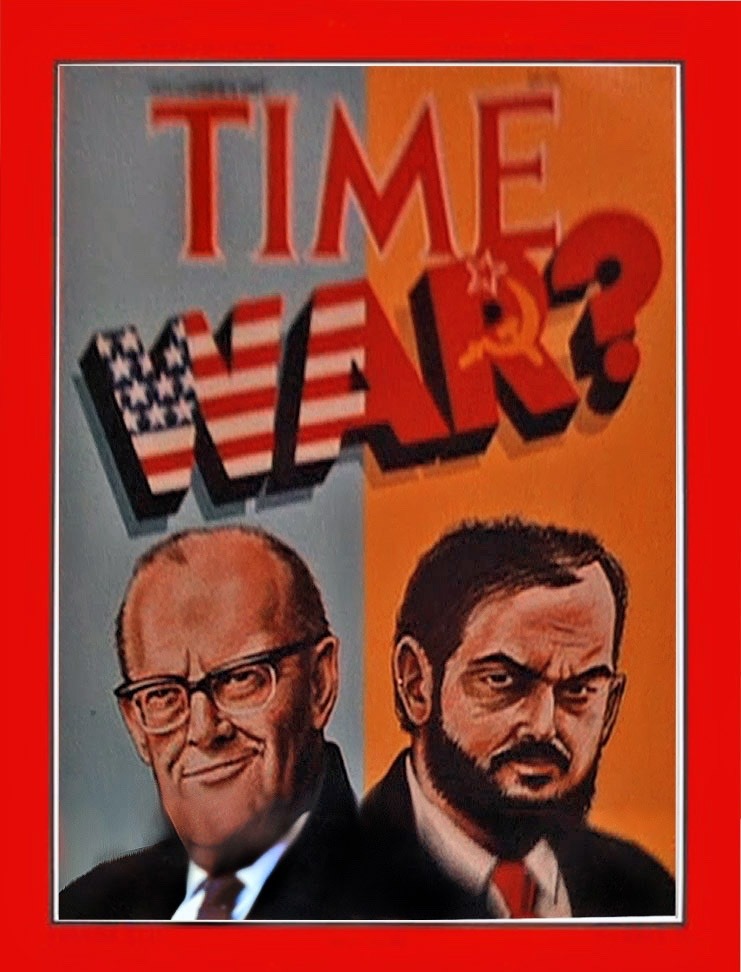

There are a good handful of other areas in which the two films dramatically diverge – politics being one. The political background of 2010 is front and center throughout the film (the “trouble” in south America; they even make a funny easter egg out of it with the Time magazine cover depicting Clarke and Kubrick as the US President and Soviet Premiere. Hardy, har-har.

There are a good handful of other areas in which the two films dramatically diverge – politics being one. The political background of 2010 is front and center throughout the film (the “trouble” in south America; they even make a funny easter egg out of it with the Time magazine cover depicting Clarke and Kubrick as the US President and Soviet Premiere. Hardy, har-har.

In 2001, the only hint of politics is the discussion on the space station between Floyd and Smetlov, and even there, its muted, unemotional and completely non-specific. Kubrick had to acknowledge the Cold War (it was 1968 and the Space Race was in full swing), but he dealt with and dismissed it in one relatively brief sequence. 2010, as mentioned earlier, starts with a secretive meeting between a Soviet scientist and Floyd.

Something is off with the backgrounding aesthetic as well. 2001 presents the 2001 future, an imaginary yet directly extrapolated extension of our world into the “Pan Am Moon Shuttle” future, comprised of a largely von Braunian/Wide World of Disney future (which, no doubt, Clarke had influence over). The rest of the world would be following suit and would be as advanced from (real) 1968 as the space station, Pan Am ship, Moon Base and and video phones as we’re shown.

2010 – not so much; Floyd’s house as a dolphin pool, but beyond that, we don’t see anything unfamiliar. Same with the hospital Bowman’s mother is in, same with the house inhabited by Bowman’s wife, same with the scenes of Washington DC – no robots on the street, no people carrying tablets, no flying cars overhead – it’s almost as if those scenes take place in a world divorced from the Jupiter-traveling space programs (of the world’s two most advanced countries at the time). Everything in 2001 following the Dawn of Man scenes is high-tech and futuristic.

Nitpicky minor stuff – the spaceships are frequently shown in motion (with whoosh), rather than the seemingly motionless reality when there is nothing in the background to offer reference. Stars are shown in the sky and in the background in space in 2010 and are not in 2001 (probably for the same reason that Moon Hoax advocates point out that stars are not visible in any of the Moon shots.

2010 starts with text and voice over – 2001 begins with strange noises and then the opening of Also Sprach Zarathustra..

And this shot

is not this shot –

I’m not saying 2010: The Year We Make Contact is a bad movie, I’m saying that, at least stylistically, it is a bad sequel.

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.