This subject ended up being a lot more involved than I had originally anticipated or realized. Or maybe in writing it I uncovered a lot more layers and nuance than I’d recognized at first. Coming to that conclusion when the majority of a longish post had already been written left me with a choice. I could either re-write everything from the beginning (with an admittedly more and better structured exposition), or I could acknowledge the change of focus and treat the original post as a wide-ranging introduction to the subject.

Owing to personal circumstance, I have chosen to take the latter approach.

In doing so, I’ll leave the original here and will address in greater detail several of the different impacts on the arts, commerce, our genre and anticipated ripple effects in additional posts.

The new technologies being discussed here represent such an enormous paradigm shift in multiply-related areas of endeavor that impact our genre that it is a fool’s errand to even attempt to discuss them comprehensively. But we’re going to try anyway. This is a website devoted to Science Fiction, after all, and what is Science Fiction if not an attempt to extrapolate our technologies in order to anticipate the impact(s) they may have on our future selves. At the very least, we expect to generate substantial discourse (if not generate no small number of story ideas).

***

Anyone can now go online and “play” with one of several different so-called artificial intelligences that can either write fiction or create drawings when given some basic parameters, such as “write a short story in the style of Ray Bradbury” or “draw an abstract illustration of a cat”.

The results are increasingly surprising, competent and often indistinguishable from art created by talented amateurs.

That’s because even a talented amateur would be able to pull off a credible effort, provided that they had previously been exposed to tens of thousands of examples, all of which they can remember in exquisite detail. (Edgar Rice Burroughs is an early example of this: struggling to make a living, he read through several pulps and determined, from those examples, that he could do as well if not better. Our assessment since 1912 has been that he succeeded.)

Currently, the debates over these phenomena are raging. Some artists and writers are outraged, protesting against the works as not genuine art…copies…forgeries…etc., while some others see these programs as mere tools, like their word processor or digital paint programs, just another tool for the mix. (No doubt some complained when the first cave wall painter showed up with ocher. “If it wasn’t done with charcoal, it isn’t art!” And I am personally not unsympathetic to their historical plight.)

Both sides of the artistic debate are correct, and both sides have missed something fundamental.

These programs will not (ever) “destroy” or “replace” human-derived artistic expression, but they will put paid to the commercialized aspects of art – and that’s a good thing.

Ursula Le Guin identified this coming clash (though not its resolution) when, in her acceptance speech for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation she said:

Right now, we need writers who know the difference between production of a market commodity and the practice of an art. Developing written material to suit sales strategies in order to maximise corporate profit and advertising revenue is not the same thing as responsible book publishing or authorship. (Emphasis mine.)

And, just a few lines later in that speech –

Books aren’t just commodities; the profit motive is often in conflict with the aims of art. (Emphasis also mine.)

Eventually, things will sort themselves out (if global warming doesn’t get us first) and commercial art will become the province of AI programs: Need some paintings for your hotel lobby? An AI will no doubt already have tens of thousands of possibilities available at relatively low cost (maybe large corporations will simply buy an art-enabled AI outright, for ALL of their commercial art needs – report covers, company retreat t-shirt designs, product illustrations, etc.). Amazon will no doubt be the first to offer “get the story you want to read” services…completely custom fiction (written in the style of – and boy, won’t that “style copyfight” be an interesting one); franchises will become perpetual, versions can be offered for different reading ages, the saga need never end….

Human beings will NOT be able to compete effectively in those environments. They need food and water and shelter, sleep, physical exercise and can’t memorize the writing styles or painting styles of any artist or author who ever produced something.

We’re not talking about the “death of artistic expression”, but we are almost certainly talking about the death of the midlist author and the commercial graphic artist.

When Amazon can tailor a book series to niche markets (I want an epic space opera that features non-carbon-based life forms; I want a fantasy novel where all the characters are from Mosul and the dragons are rainbow-hued…) and deliver entire novels and series in minutes…there is not a single person on the face of the planet who can compete. Not even James Patterson.

Robert Heinlein famously opined that authors (and, by extension, artists) are not competing with other authors, but are, instead. competing for “beer money” – disposable income – and that what they write has to be intriguing and interesting enough to convince a consumer to spend their entertainment money on a read instead of a film or a streaming service or going to the bowling alley. (For a number of years I made that choice at the expense of the author himself, choosing to spend that beer money on paintballs instead of books.)

Well, the new and emerging “art” AIs are going to somewhat alter that equation by maybe putting authors in competition with themselves. Sort of.

Suppose you are a real die hard Heinlein fan. You’ve read everything, even the two attempts at stretching out his bibliography for the franchise effect (Variable Star, Pursuit of the Pankera) and you still want more.

So you pays your money to (Amazon or whichever conglomerate now owns the author’s rights) and their AI churns out a new novel “in the unique style of America’s Science Fiction Grand Master, Robert A. Heinlein”!

Since you’re given some latitude when ordering, you decide to fill in the “Future History” and order a copy of The Stone Pillow.

Having read ersatz Heinlein (and finding that it fills that RAH-sized void), you decide to pay a little extra (and, in the face of $12.99 off-the-rack paperbacks these days a couple of bucks is a bargain!) and order a completely new “In the Style of” novel: the sequel to The Door Into Summer.

Meanwhile, living, breathing, contemporary authors find that Amazon and their ilk aren’t buying anymore.

In fact, traditional publishers are failing left and right as most fail to win in the bidding wars to acquire IP rights to a sufficient number of name “legacy” authors (the battles over Nora Roberts and Tom Clancy actually got bloody!).

New talent:? New points of view? Hah! All you have to do is type in “The Turner Diaries in the style of Samuel Clemons”, and you’ll have all the “new” you can possibly handle. (Or maybe try Das Kapital in the style of Sean Hannity; Little Women as written by Pauline Reage; Starship Troopers in the style of Joanna Russ…You’ll have to forego Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, already been done.)

These new technologies are the toy every reader has always wanted but never knew it. All those a-holes who bitch out authors for not finishing a series quickly enough (GRRM, we’re looking at you) have now got their wish. David not finishing his giant worm series to your satisfaction? Bring in the AI.

We’re not just talking books on demand. We’re talking story-telling on demand.

And even more than that, we’re talking about the fact that dumbing things down to appeal to a larger audience has now had its lower limits entirely removed. There is no longer a low to which we won’t go. I simply can’t wait to read the (in the style of) Dr. Seuss edition of Gravity’s Rainbow.

(Text books are an entirely different niche but they bear keeping an eye on. Texas will be able to demand a new history book every year, for each of its grades, and a history that entirely removes anything the current Texas regime finds objectionable. White washing, bowdlerizing, excising, expurgating, altering the meaning of, just became the primary purpose of text book creation.)

I’m trying very hard to imagine a publisher that manages to survive in that competitive environment while continuing to publish traditional – as in written by living, breathing, eating, shitting, mortal human beings. I’m trying to imagine an editor in that environment ever saying anything even closely resembling “if that’s the way you want it, we’ll leave it in there” to an author. The dichotomy is so stark, when this technology becomes commercially available, there is just simply no room for continuing things the way they are done now.

A quick survey of things that will change for publishing as it is now should be sufficient to make the point (sufficient, but far from comprehensive):

Submissions – entirely eliminated

Readers reading submissions – entirely eliminated

Finding new content that fills a marketing niche – entirely eliminated

All manner of other incidental expenses associated with working with living human beings – almost entirely eliminated (when marketing comes down to letting subscribers know that their latest offering is now available, you pretty much don’t need entire departments anymore: no art directors, no design specialists, no font stylists, no promotion coordinators….)

Deadlines – never slipped

Lead times – virtually non-existent

Never ever hear anything like “I’ve had writer’s block”

Never have to pay royalties for entirely original work (and probably no fee for works covered under IP rights purchased out right)

Never again have to tell an author that you can’t find an appropriate niche for their work

Never again have to wonder of the author is actually going to deliver the story as agreed upon

Editing process – almost entirely eliminated (no copy editing needed, no developmental editing needed, no continuity editing needed…)

Never have to employ sensitivity readers again

Translators entirely unnecessary

Book covers created to match individual niches at no additional cost

There are oodles of other advantages, most of them falling into the category of not having to rely on living human beings. For example, there will never again be a novel that wasn’t finished because the author died mid-process.

Books will be written in near zero time; they can be tailored to meet whatever parameters are desired for a particular market; the same “story” can be churned out in multiple versions for different age groups, different political sensibilities, religious concerns; the same book can be sold in any language market with no additional associated costs for translation; cultural taboos can be tailored; every minority audience can be represented in every story (different versions) and readers can customize their reads so that they are always getting “four star” work.

Oh, and book reviewing? Dead. First, the volume will be overwhelming (as if it isn’t already) and secondly – there’s no point in reviewing custom work. (Review: “Readers will be disappointed by this book that is entirely customized for each individual…”? A bit of expansion on this extrapolation: No one can effectively object to the “politics”, “wokeness”, “slant”, “objectionable advocacy” or even “facts” when a version of a book AGREEING with critics can be generated as soon as the objections are voiced. Talk about the end of objective reality….)

You want to talk about a paradigm shift, this is it.

Or, perhaps another way to look at it is – it’s the triumph of so-called transformative works over originality in the commercial realm.

That statement doesn’t come out of left field.

I was pretty upset when AO3 won a Hugo award for Best Related Work (and said so at the time), as doing so essentially put the works of people violating the intent of copyright on par with those who create original work. (I’m consistent: the entire philosophy that exempts such things from being a violation was, for me, the original “colorizing” decision – Ted Turner’s colorizing of black and white film* was determine to change the original to such a substantial degree that it was transformed into a new original work. Among other things, this lets a so-called artist who shall remain nameless copy comic book graphics, “colorize” them and then sell (someone else’s) work as if it were their own. Why struggle with originality and creativity when you can simply change names and rewrite scenes and then re-title it as Shades of Something….?

Standing still for that original decision lasted until very recently. Now, courts are tightening the definition as things have been getting out of hand.

But lets not get off on a tangent. The bottom line is, the legal decisions that make a website like Archive of Our Own legal are the same ones that will allow AI-based “authors” to create works that play in other people’s universes (and after a generation it won’t matter anyway as all of the content that is protected by copyright right now will have entered the public domain – not to mention the continued attempts to erode the length of copyright, largely in an effort to force Mickey Mouse entirely into the public domain. But I digress. Again.).

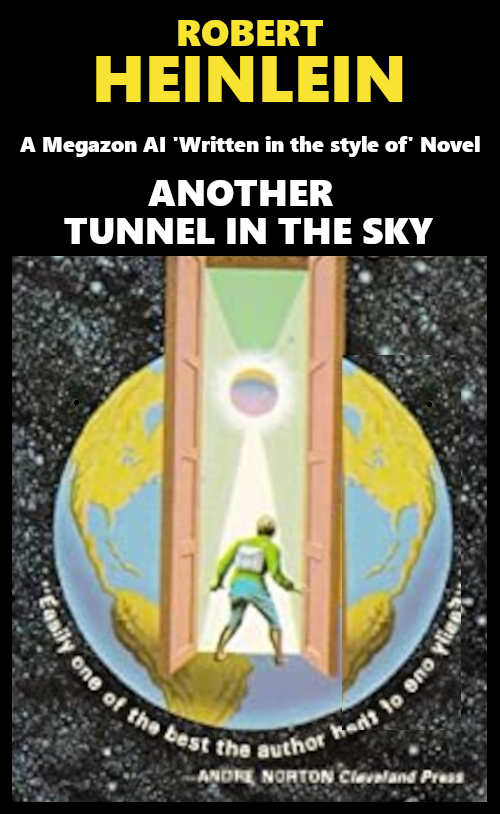

Sure, the Heinlein estate may very well object to direct sequels – but there’s nothing they can do about stories offered up as “in the style of”. Bob’s name is, sadly, not trademarked and you could never copyright titles. FYI: There are 38 individuals living in the United States today named “Robert Heinlein”, 132 named “Arthur Clarke”, 25 named “Ray Bradbury”, 5 “Larry Nivens”, 275 “Harry Harrisons”, 11 “Octavia Butlers” and 498 “Steve Davidson”s. Nothing, legally, prevents anyone – including an AI – from using a particular name as a pseudonym. A Second Tunnel in the Sky by AI as written by Robert Heinlein would be a perfectly legal title to stick on a novel offered by Megazon, the soon-to-be dominant company in the AI Publishing sector.

Not shown in the illustration is the registered trademark symbol that ought to accompany the phrase “Written in the style of”….

(I’m using a portion of the cover art from one of the legitimate editions of Tunnel in the Sky for illustrative purposes here. Of course, the actual rip off book’s art would have some slight alterations to the original and a statement that the artwork was created by a different AI “in the style of” whoever the original cover artist was.)

I don’t expect everyone to agree with this interpretation of these aspects of copyright law. But I do expect most everyone to recognize the slippery slope we’re teetering on the precipice of.

Will there be lawsuits? Sure thing. Unlike midlist authors, IP litigators are probably eagerly anticipating all of the billing hours this new technology will support.

I have so far focused on the written word when, in fact, the impact of AI-generated art is already being felt. I had hoped that Amazing Stories would be the first science fiction magazine to publish an AI-authored story accompanied by AI-created artwork, but I think that’s already happened.

Online art programs offering users the ability to have an AI program create art from prompts number in the dozens. One – crAIyon – created the following three sets of images from typed suggestions in under 2 minutes each. No, they wouldn’t go on the cover of Amazing Stories (a couple are pretty close though), but they’re all sufficient for helping an author/editor and art director getting together to refine the look of their final product.

(Have to admit, a few of the alien images are sufficiently disturbing.)

You should read that as saying something like “AI art programs are already sufficient for creating storyboards”. All in 2 minutes or less. (If you go and read accounts of, say, the production of Star Wars in 1975, 1976, you’ll find numerous mentions of days, even weeks, passing between the request for art and reception of the same.)

One astronomical artist I am familiar with (Ron Miller) has been playing with an AI and sharing the results with friends on Facebook. His attitude is generally of the “just another tool” variety.

I’m waiting while someone finishes educating an AI on comics and graphic novels, at which point they’ll be able to combine the two disciplines. That should scare anyone currently enjoying Gaiman’s Sandman on Netflix. (Hooking an art AI up to a 3D printer ought to cover sculpture….)

And so?

The so is that within less than a generation, the ability to make a living with commercial expressions in artistic fields will no longer be a possibility.

The very important word here is “commercial”. If your idea of an ideal life is writing romance novels for a living, you better find a day job. And I don’t mean a day job like most commercial authors have these days (very few live that ideal life), I mean, you better think of another profession entirely, because there will be no publishers accepting submissions, no agents taking on new clients, no blogger gone viral getting a sweet deal for the story his friends all really, really, really liked.

All of that will be handled by machines (and the megacorps that own those machines: a recent court decision removed the ability of AIs to acquire other intellectual property in their own right).

As will the cover art gigs, the custom convention badge gigs, the furry character gigs…there won’t be any table in artist alley at the con because there will be no artist alley.

People will still dabble, of course. There will also be a substantial, though steadily diminishing, “traditional art” market, where people with too much money on their hands will pay outrageous fees to insure that NO machine intelligences were involved in the production of whatever it is that is produced, but they’ll all be novelty acts, things supported by unwashed elites, the nouveau riche, and scholarly types who still remember who Shakespeare was. (Think metropolitan opera companies, civic sculpture gardens, legacy printed newspapers.)

I want to stress that it is not the fault of our creative class that this is and will happen. Not theirs at all. They’re being victimized even more than the consumer is. But no human being can compete with a machine’s ability to deliver EXACTLY what a reader or viewer wants, minutely customized for each individual consumer, and to deliver that product in SECONDS. These represent insurmountable obstacles for anyone who wants to create art from which they can earn some income.

(The AIs are already encroaching on the commercial voice talent arena, just as voice recognition software has pretty much eliminated the need for anyone to take dictation.)

It won’t be long before the vast majority of our commercial entertainment is created by AI programs, under human supervision, of course, though the need for that supervision will slowly diminish as well.

At that point, not only will the AIs be creating the art, they’ll also be telling us what we should and should not like.

But that end stage is a couple of generations away (AI generations). For the nonce, we can all look forward to an explosion of affordable, customizable artistic expression.

I wonder if the Hugo Administrators will accept an AI author as itself eligible for the Best Related category…?

*That’s actually not accurate. The case that established transformative rules was one based on Rap music and sampling…which I also believe violates copyright despite the legal decision in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music. Stealing someone’s lyrics is ok if you use them with a different tune…I’m not the only one who has dissented on this particular slippery slope, but I do have the satisfaction of seeing it starting to be curtailed

**Harlan Ellison was a bit more prescient than most. His name IS Trademarked (IC 016 – for “Printed matter, namely, books and magazine columns featuring general fiction and non-fiction about the subjects of popular culture, penology, social commentary, film and television criticism, theory of creative writing, anecdotal and biographical material, literary anecdotes, science fiction, fantasy, horror and the supernatural, American authors, radio, television, entertainment and book reviews”), so if you want to use THAT name, you’ll need a license. On the other hand, you still won’t need a license for stories written in the style of Harlan Ellison(R). Harlan Ellison is a registered trademark of the Kiliminjaro Corporation and that trademark is used here for illustrative purposes only. A similar disclaimer will accompany any works “written in the style of”, stories such as “Repentance is Useless, Ticktockman!” or “I Just Got A Mouth So I Am Screaming!” or even “Look, Jefty Got A Tiny Man When He Was Five“.

***Our featured image is original artwork, commissioned from and produced by an actual human being – Al Sirois.

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.

Recent Comments