A creature resembling a cross between a moth, an owl and a devil fish stares into a transparent, ovoid object. Behind it is a landscape of red cliffs and weird buildings; other members of the creature’s race can be seen flying above a body of water. It was May 1926, and Amazing Stories – the magazine that promised “Extravagant Fiction Today, Cold Fact Tomorrow” – had delivered its first visual portrayal of an extra-terrestrial lifeform.

A creature resembling a cross between a moth, an owl and a devil fish stares into a transparent, ovoid object. Behind it is a landscape of red cliffs and weird buildings; other members of the creature’s race can be seen flying above a body of water. It was May 1926, and Amazing Stories – the magazine that promised “Extravagant Fiction Today, Cold Fact Tomorrow” – had delivered its first visual portrayal of an extra-terrestrial lifeform.

“THANK YOU!” begins Hugo Gernsback in his editorial. “The first issue of AMAZING STORIES has been on the newsstands only about a week, as we go to press with this, the second issue of the magazine; yet, even during this short time, we have been deluged with an avalanche of letters”. He continues:

And it was with a feeling of gratification that we noted the almost unanimous condemnation of the so-called “sex-appeal” type of story that seems so much in vogue in this country now. Most of our correspondents seemed to heave a great sigh of relief in at last finding a literature that appeals to the imagination, rather than carrying a sensational appeal to the emotions.

Gernsback goes on to quote from some of the enthusiastic letters that he received, before announcing some of the authors who would be published in future issues – including, by popular demand, Edgar Rice Burroughs. But newcomers to the magazine are in short supply within Amazing Stories #2, as the issue is focused upon wrapping up stories from the debut instalment.

“Off on a Comet” by Jules Verne

Amongst these is Jules Verne’s Off on a Comet, which concludes its two-part serialisation. The latter half sees the inhabitants of the comet Gallia conducting field research to discern the size and speed of their new home, and so work out when it will next come into the vicinity of Earth.

Amongst these is Jules Verne’s Off on a Comet, which concludes its two-part serialisation. The latter half sees the inhabitants of the comet Gallia conducting field research to discern the size and speed of their new home, and so work out when it will next come into the vicinity of Earth.

Their plans are undermined by the miserly con-artist Isaac Hakkabut, who treats science as a mere money-making opportunity. The anti-Semitic aspects of the story reach their peak here, with the Jewish Hakkabut being portrayed as a serpent in the scientific Eden:

Gallia continued its course, bearing its little population onwards, so far removed from the ordinary influence of human passions that it might almost be said that its sole ostensible vice was represented by the greed and avarice of the miserable Jew.

When the comet approaches Earth once more, protagonist Captain Servadac and his cohorts reach terra firma in a hot-air balloon built from the sails of their schooner. Verne was clearly aware of this idea’s implausibility, and jokingly acknowledges it when Servadac describes balloon travel as being so outrageous that even novelists rarely portray it – Verne’s fans, of course, would have known that the author made his name with Five Weeks in a Balloon, published in 1863.

When the characters arrive safely on Earth, they find that – absurdly – no-one else even witnessed the comet on either passage. Their story is so roundly dismissed that even they themselves start to doubt it, adding a “was it all a dream?” ambience to the novel’s conclusion.

“The Man From the Atom” by G. Peyton Wetenbaker

Also concluding in this issue is G. Peyton Wetenbaker’s story “The Man From the Atom”. Stranded on an alien world, protagonist Kirby is taken to a city by a race of humanoids. During captivity he is treated as a mere curiosity by most of the civilisation, but the beautiful alien princess Vinda takes a liking to him.

Also concluding in this issue is G. Peyton Wetenbaker’s story “The Man From the Atom”. Stranded on an alien world, protagonist Kirby is taken to a city by a race of humanoids. During captivity he is treated as a mere curiosity by most of the civilisation, but the beautiful alien princess Vinda takes a liking to him.

The story makes a few token attempts to flesh out its aliens, giving them a language “related, perhaps, to the vague thing we call mental telepathy”. On their world, all forms of artistic pursuits and pleasure, even laughter, are seen as specifically feminine: “They did, indeed, scorn me, those men, when they saw me laughing, as we would scorn a man who talked with a piping voice and giggled and stepped mincingly about.”

Speaking with Kirby, Vinda goes into more detail about the social make-up of her planet: “The men were creators and teachers. They discovered, invented, reproduced, perfected endless marvellous things. Women, on the other hand, understood them only in the detailed way of those who tend them, watch over them, care for them.” Wetenbaker never really builds upon these cultural concepts, however, and uses them simply to add an exotic backdrop to Kirby’s adventure.

When Kirby tells Vinda about the theories of Einstein, she outlines theories held by scientists of her own race: “our evidence has taught us that time goes in circles, in cycles. They say that, if one were to live forever, he would find eventually the whole of history repeating itself.” This alien science has also established that “there is a direction, which we cannot quite grasp mentally any more than we can grasp time as a direction, which extends from the small to the great” – a loose attempt to elaborate upon how time travels faster for Kirby the larger he gets, as established in the first instalment.

After making some calculations, Kirby reactivates his scale-altering gadget and enters the fifth dimension of size, ending up in a future year on Earth that corresponds with the one in which he left. He finds that, following his disappearance, his mentor Martyn was imprisoned for manslaughter: “It seems that laws were enacted all over the country for the ‘restraint’ of scientists, who were said to constitute ‘the greatest menace to our country since the civil war.’”

This iteration of the universe is not identical to our own – Teddy Roosevelt turned the United States into a monarchy, for one thing – but Kirby does not stick around to explore. Pining for Vinda, he decides to grow his way into the future once more and meet her current incarnation. His only concern as the story closes is that he may end up battling his own double for her love: “How impossibly it savors of Poe and William Wilson!”

“Mesmeric Revelation” by Edgar Allan Poe

Speaking of which, the issue’s Edgar Allan Poe story is another continuation – in thematic terms, at least. Amazing Stories #1 ran “The Facts In The Case Of M Valdemar”, an 1845 story in which a hypnotist places a tuberculosis patient into a trance, and later finds that the man has been talking even after he died; Amazing Stories #2 includes “Mesmeric Revelation”, an 1844 story with the same plot but a significantly different emphasis. While “M. Valdemar” is essentially a horror story, built around the final, visceral scene in which Valdemar’s body suddenly decays into a pile of flesh, “Mesmeric Revelation” is a thoughtful piece which tries to provoke its readers into considering the nature of survival after death.

Speaking of which, the issue’s Edgar Allan Poe story is another continuation – in thematic terms, at least. Amazing Stories #1 ran “The Facts In The Case Of M Valdemar”, an 1845 story in which a hypnotist places a tuberculosis patient into a trance, and later finds that the man has been talking even after he died; Amazing Stories #2 includes “Mesmeric Revelation”, an 1844 story with the same plot but a significantly different emphasis. While “M. Valdemar” is essentially a horror story, built around the final, visceral scene in which Valdemar’s body suddenly decays into a pile of flesh, “Mesmeric Revelation” is a thoughtful piece which tries to provoke its readers into considering the nature of survival after death.

The hypnotist narrator is sceptical about the existence of the soul: not even Orestes Brownston’s book Charles Elwood; Or, The Infidel Converted has convinced him. But things change when he places a terminally ill man named Vankirk into a trance, and begins a lengthy theological discussion with this patient.

During the course of this conversation Vankirk states that the universe is the mind of God, and so human beings – as God’s thoughts – naturally contain fragments of the Almighty. He also confirms that there are intelligent beings elsewhere in the cosmos, which likewise have immortal souls.

When it is time to wake Vankirk, the patient drops dead with a blissful smile on his face. The narrator ends the story by pondering whether at least part of Vankirk’s dialogue was spoken from the afterlife.

It is not hard to see why “Mesmeric Revelation” today stands as one of Poe’s more obscure works, particularly compared to the superior “M. Valdemar”. Poe relies heavily on the notion of luminiferous ether, which was current in nineteenth century science but, by the time the story was published in Amazing, had long been replaced by the theories of Albert Einstein. Still, Hugo Gernsback found plenty to praise about this tale:

It is a great mistake to take this favourite author as only an agreeable fiction writer, and it is impossible not to feel that had his life been different, had he not been overshadowed by poverty, and had he not led so troubled an existence, he would have figured as an enlightened philosopher, and one whose views are far removed from the disagreeable pessimism so prevalent of the present day.

“The Crystal Egg” by H. G. Wells

Naturally, H. G. Wells turns up once more. In “The Crystal Egg”, two men visit an antiques shop after seeing the titular object displayed in the window. But proprietor Mr. Cave is reluctant to part with the egg, even for the hefty sum of 5 pounds; the two customers find this baffling – as does Cave’s family, who would benefit from the money. The crystal egg later goes missing.

Naturally, H. G. Wells turns up once more. In “The Crystal Egg”, two men visit an antiques shop after seeing the titular object displayed in the window. But proprietor Mr. Cave is reluctant to part with the egg, even for the hefty sum of 5 pounds; the two customers find this baffling – as does Cave’s family, who would benefit from the money. The crystal egg later goes missing.

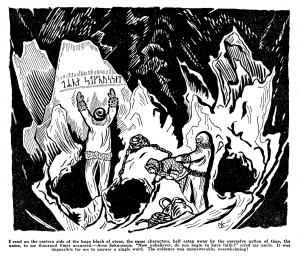

At this point, the story’s narrator fills us in on the details. The egg was hidden by Mr. Cave, who knows of its singular property: when he looks into it from a certain angle, he can see a landscape of weird cities, trees, and insect-like creatures which sometimes peer back at him. An acquaintance of his, a scientist named Wace, examines the egg and concludes that these beings are the inhabitants of the alien cities (this clearly captured the imagination of Amazing‘s house artist Frank R. Paul, whose interior illustration shows an original scene in which the aliens are operating some sort of plant). The narrator, meanwhile, informs us that the creatures are most likely Martians, and that the crystal egg was presumably sent to Earth as a means for the aliens to study humanity.

The elderly Cave’s health fails, and he is finally found dead – clutching the egg, with a smile on his face. The egg is sold on, and both Wace and the narrator attempt fruitlessly to find its present owner.

“The Crystal Egg” is a curious tale that can be seen as a transitional point between science fiction as we know it today and an earlier form, the ghost story. The plot has a structure found in many ghost stories: a person obtains a mysterious object (in this case, one with obvious occult associations: a crystal ball), the object turns out to be connected to a non-human intelligence, the owner dies, and the reader is left with a lingering mystery.

But they key difference is that – bearing in mind that Cave’s death is from natural causes – the artefact of “The Crystal Egg” lacks the element of malice or danger essential to a ghost story. Its properties are not scary, but fascinating. While ghost stories traditionally intend to leave the reader apprehensive about having such an encounter in real life, “The Crystal Egg” is instead designed to leave the reader frustrated that such a wondrous scientific discovery has slipped through Wace’s fingers.

“The Infinite Vision” by Charles C. Winn

Again, Amazing Stories dips into the Hugo Gernsback back-catalogue for material, this time reprinting a 1924 story from Science and Invention. The author, Charles C. Winn, appears not to have had any other fiction published.

Again, Amazing Stories dips into the Hugo Gernsback back-catalogue for material, this time reprinting a 1924 story from Science and Invention. The author, Charles C. Winn, appears not to have had any other fiction published.

While an astronomical society squabbles over the unsatisfactory performance of its latest telescope, one of its members – Glenn Faxworthy – announces his plain to make a telescope “which will reveal the molecules of the rocks of the moon.” Ten years later, his new telescope is ready to unveil.

The story describes the build-up to its demonstration with hushed awe. Faxworthy then explains the workings of his invention, which relies on a newly-discovered element called Lucium; this “has the same properties as selenium, only in a million times more sensitive a degree.” His explanation only goes so far, however: as he acknowledges, some of the details are too complex to expound in such a short amount of time.

After providing a look at moon molecules, Faxworthy turns the telescope to Mars. The assembled scientists are treated to the sight of Martian city populated by beautiful people, clad like ancient Romans and piloting airships. Also present in this city is an observatory, the telescope of which is pointed right back at Earth – obvious shades of “The Crystal Egg”.

Suddenly, the ray which protects the terrestrial observatory weakens, and the scientists are killed by a storm that has been raging outside. Exactly what causes this calamity is unclear; Winn resorts to invoking an anthropomorphised Nature, as though Faxworthy and company have been struck down by divine intervention: “And, above in wild cadence the thunder drums of Nature rolled out a pean of victory, over the shattered fragments of the rash mortals who fain would know her innermost secrets.”

“The Infinite Vision” is a clumsy and inconsistent piece of work. The story starts out as Gernsbackian SF at its purest, designed to illustrate a potential scientific development while sacrificing plot and characterisation. With the introduction of the classically-derived Martians, it becomes fantasy. Finally, it closes on a deeply conservative note as the scientists are slain for their supposed transgression. Earlier stories in Amazing had cautionary tones, but “The Infinite Vision” is the first to actually punish its protagonists for scientific investigation.

A Trip to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne

As well as wrapping up Off on a Comet, Amazing Stories #2 begins a serialised translation of Jules Verne’s 1864 novel Voyage au centre de la Terre. Regrettably, the magazine chose the poor-quality translation prepared by British publishers Griffith and Farran. This version takes tremendous liberties with Verne’s text; not even the main characters’ names remain.

As well as wrapping up Off on a Comet, Amazing Stories #2 begins a serialised translation of Jules Verne’s 1864 novel Voyage au centre de la Terre. Regrettably, the magazine chose the poor-quality translation prepared by British publishers Griffith and Farran. This version takes tremendous liberties with Verne’s text; not even the main characters’ names remain.

The novel introduces us to Professor Hardwig (Lidenbrock in Verne’s original) who stumbles upon a historical document pointing to an entrance to the Earth’s core in an Icelandic volcano. The Professor’s nephew, Harry, narrates the story but only reluctantly joins his uncle on the expedition.

As the pair, along with their guide Hans, begin their descent into the volcano – much to Harry’s chagrin – the first instalment ends, ready for the adventure to be continued in Amazing Stories #3…

Read My Profile