Fanzine review: GROGGY #2, 3, 8 & 9

Groggy #2 (Jul 78), #3 (78), #8 (79), #9 (Mar 80)

Faned: Eric Mayer

These issues of GROGGY were originally traded to Susan Wood*, a University of B.C. Professor who was also a very active and quite famous fan, and were willed to the B.C. SF Association, along with much of the rest of her fanzine collection, after her untimely death.

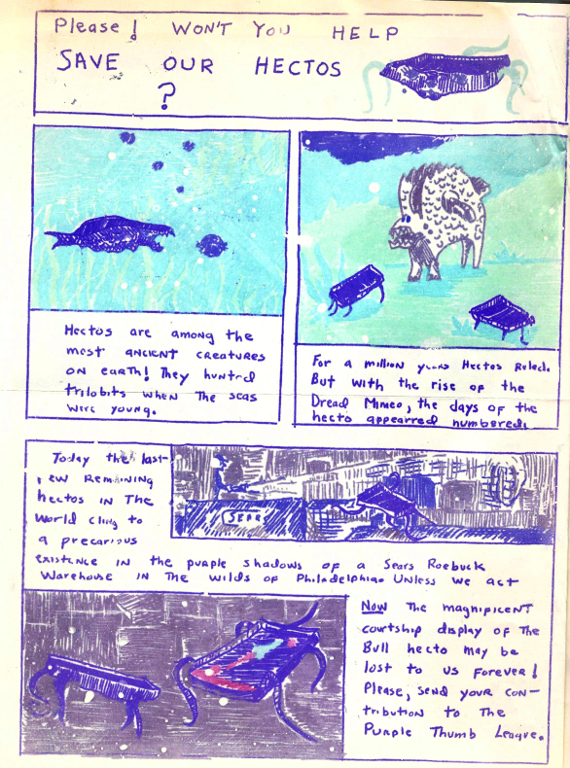

Groggy was entirely hectographed (or hektographed), something of a dying art form even as early as 1978, but a process Eric evidently and obviously mastered.

As I understand it, first a pan was filled with a type of gelatin that sets fairly solid. Next a master copy of the page desired, created with one or more hecto pencil inks or typed and drawn on a hecto carbon, is laid on the gelatin. The majority of the ink sticks. Remove the now faded master copy. Next lay a blank sheet atop the gelatin. Enough image forms to duplicate the master. Remove. Put on another blank sheet. Of course, with each sheet more and more ink is drawn from the gelatin. Eventually the reproduction becomes too faint to read. If you are lucky, you can get fifty more or less good copies of the original. Then you have to empty the pan and prepare a fresh bed of gelatin for the next page of the zine.

Usually this method was used just to duplicate text, most commonly in purple ink since the majority of hector carbons available came in that colour. Eric employed both purple and green, sometimes on the same page, which meant two runs for each page on separate beds of gelatin, or three if a multi-coloured image drawn by hecto pencils was utilized. Or maybe the separate masters were imprinted on a single bed of gelatin. Not knowing much about the process, all I can say is there is visual evidence of multiple “passes” on some of the pages, the combined text and images not being quite aligned to each other. Point is, judging by GROGGY, typed text could be either purple or green, and any other colour had to be hand-written on the master.

The purple ink is more or less identical to the colour most commonly used in spirit duplicators. People often assume that purple was the only colour available to the latter. Not true. However, hecto pencils offered a greater range of colour (according to what I’ve read) including some very subtle shades within a given colour.

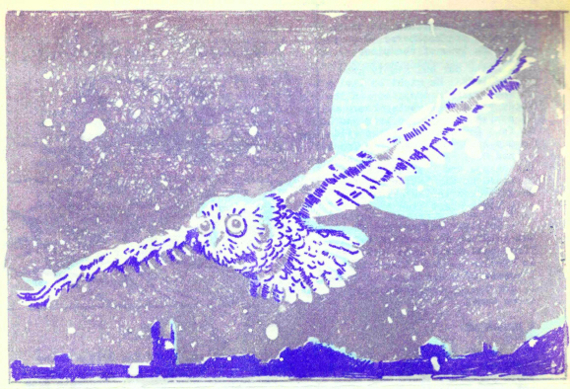

Looking at the fading images in the four issues of GROGGY the BCSFA archive possesses, Eric utilized purple, red, dark green, light green, and brown. I don’t see so much as a hint of any other colour. A very limited palette, yet Eric achieved remarkable results.

The thing to remember is, fresh hectography is remarkably bright and vivid. Over time, the colours fade away to nothing. This is why I keep these issues in plastic wrap envelopes within paper envelopes. Trying to keep both oxygen and light away from the vulnerable ink. Fresh hectography text is very easy to read. Old zines printed with this method are often indecipherable, with readable portions, if present, in the form of blotchy patches scattered among the pages. It’s like trying to read fragments of an ancient papyrus scroll. You catch glimpses, but the text in its entirety no longer exists.

I have manipulated my scans to bring out the details and the colour. In the case of GROGGY #8, the “Aardvark” issue, the green ink employed to depict the “Giant, Mind-Reading, Homosexual Aardvark from Outer Space” is so faint my efforts to bring out the line drawing resulted in the white background becoming distinctly yellow. Sorry about that, but I wanted to illustrate how artwork reproduced by hecto methods can be just as illustratively detailed as line drawings reproduced by other means. This particular piece was drawn by Gary Deindorfer.

For many teenagers back in the depression era hectography was the printing method of choice, since its components cost very little, apparently. On the other hand, laying a blank sheet gently but firmly on gelatin sounds iffy to me. How easy to push too hard, or to lightly, or to misalign a page, or to misalign separate “blocks” when pressing the same page on more than one bed of gelatin to combine images. Above all, how easy to smear purple ink all over yourself, a dreaded phenomenon known as “Hectographer’s Hands,” with particularly bad outbreaks involving the forearms and even the face if you don’t watch where you put your fingers. The same disease afflicted spirit duplicator operators on occasion. According to Richard Eney in his Fancyclopedia #2, the Ditto company manufactured a special soap to deal with the problem “but really it only comes off when the skin does.” I suspect hecto fans wore their “colours” as a badge of pride.

Eric himself had this to say in issue #3: “This is the July 1978 issue. Print run 65. To be fair the first, clearest part of the print run will be sent out to those I’ve heard from since last issue.”

“It had to be hecto. Wonderful hecto. I’m not going to belabor you with the problems one faces trying to publish a fanzine with a tray of jelly and some ditto masters. Aside from ten minute disco drones and recitations of Bob Dylan’s lyrics there are few things in life so boring as a faned’s descriptions of his solitary struggles with balky repro equipment. For anyone interested, the whole sad tale is smeared, blurred, faded and blotted across evey page of CHARM #1. Hectographs, like cats, have minds of their own and refuse to relinquish their basically primitive natures. But it had to be hecto because hecto is cheap.”

“In the interests of fandom’s eyesight, I tried to put this fanzine off, but I’ve been making ‘magazines’ for as long as I can remember—since before I could write. My best friend and I would sit out on the porch in summer, drawing endless comic strips on the rolls of adding machine paper my grandfather brought home from work. We told each other stories as we drew along. In those youthful days I wasn’t much concerned with circulation.”

“Only later did repro become le bête purple it has remained. When I was in the fifth grade I solved the problem by renting out my single copy of MORGAN THE TALKING DOG COMICS but I got so tired of erasing the crossword puzzle after every reader that the second number never came out.”

“So things are getting better.”

In the next issue (#3) Eric had this to say about his zine and his printing method of choice:

“You never have to worry about mailing labels in GROGGY. I despise the things, as any editor who’s chopped me off his mailing list can tell you. From my own experience, I think most readers who don’t respond after a decent interval are pretty much in the clutches of GAFIA and totally paralysed. Warning them of their impending doom is as cruel as telling a terminal cancer patient he has only a month to live. If you simply must know what your status is, try reading GROGGY in a dimly lit room. If you can’t it’s probably time for action since the clearest, brightest copies go out to those readers I’ve heard from recently and others get the foggy end of the print run.”

Thus the advantage of a hardcopy zine physically mailed to readers as opposed to e-zines posted online. Readers of e-zines can go on reading every issue even if they never send so much as a single letter of comment, whereas the recipients of hard copy zines will miss out if they don’t respond. The modern computer age has removed all the punitive fun of being an editor! Though, I suppose, one could avoid posting online and simply email copies to a subscription list, threatening to remove anyone and everyone who doesn’t reply with comments. Still, not quite the same thing, somehow. At any rate, rising postal rates have killed hard copy mailings except by die-hard traditionalists who eat nothing but Kraft Dinner and day-old bead to save on unnecessary mundane expenses. Or such is my impression.

He goes on to say, “I admit that I come down with a touch of the old egobooflu when I come in eye contact with enjoyable, elaborate fanzines like KNIGHTS and MAYA, but I always recover quickly enough to save myself from any complications. It’s all very nice to reach 500 people rather than 50 but pretty soon other fans have to start subsidising you (and any fan who subs half a dozen semi-prozines has laid out enough money to do his own hectoed zine) and you start worrying about printing stuff by Big Names and general interest things to please some amorphous majority, and then there’s FAAns to be worried about and, if you write for other zines, you start to check circulation figures before submitting. It’s just cheapjack professionalism really and what compensation do you get for turning your hobby into another job? It’s not for me. No way. I’ll just keep hectoing along and confine my dreams to the remote possibility of a used spirit duplicator that might put me in touch with 100 readers, each of whom would get a good copy. In the meantime this goes down on the resume as ‘Hobbies –editor and publisher of limited circulation magazine with international readership.”

On the subject of locs Eric writes: “The response to GROGGY has been remarkable. I could easily print a letter column twice as long as the entire last issue! But if GROGGY is to continue as a small, frequent personalzine (indeed, if it is to continue at all, considering my budget) I have to control the seemingly evolutionary urge toward gigantism. So I hope you don’t mind if I steal a page from DOWN MAGAZINE and print some …”

“BITS & PIECES”

“I love receiving any and all letters, even when the writers won’t let me print them. (Hi, Gil.) TIM MARION and DAVE SUZUREK both wrote me to explain why they couldn’t send me a proper loc. Please rest assured that “proper locs” aren’t necessary here. I’ve read masterpieces that didn’t contain any comment hooks and wouldn’t have elicited a ‘proper loc’ from me. As an editor and letterhack, I happen to think that a loc is primarily a way of communicating with the editor, thanking him for sending along his fanzine and letting him know whether or not you liked it. To me getting part of a letter published is just a happy accident, a by-product of my interaction with an editor. Some of the larger fanzines are only giving out ‘credits’ for published locs. Where this leaves strictly personal communication between the editor and the reader, I don’t know and I’d rather not find out.”

Here are some examples of locs and how Eric responded:

From: Allen Cadogan – “I virtually never respond to fanzines, mostly because most of those I get are incredibly dull. (Makes me wonder if anyone reads mine.)”

Eric responds: “I know the feeling. I hate to admit it, but I find many fanzines tedious. There are too many unedited letter columns, too many artists who substitute breasts and beanies for imagination, too many writers who ramble all over their seemingly endless supplies of stencils rather than actually writing. I’ve never read a fifty page fanzine that wouldn’t have been twice as good at half the length. Of course I often wonder if anyone is amused by GROGGY, self-indulgent as it is. Opinions do differ.”

Also from Ellen – “Don’t know if the pages that looked like they were rained on really were rained on or if that’s just the result of end-of-print-run.”

To which Eric replied, “What it is, is the difference between copy number three and copy number fifty three. You might be one of the few fans in history to have locked the fifty third copy of a hectored fanzine! I wonder what the biggest recorded print run for a hectoed fanzine is?”

Harry Warner Jr., on the other hand, receiving the third copy of issue #2, writes – “The hecto illustrations remind me of a color television set with the color intensity control turned up a trifle higher than normal.”

The vivid colours practically leaped off the page I’m sure. Harry always slipped the gazillions of zines he received into paper envelopes and stored them in his attic. The Texas millionaire who know owns the collection (probably the best and most extensive zine collection in the world), hired a curator to catalogue and study them. Probably the issues of GROGGY in the collection are in pristine condition or close to it. Oh, to be that curator! The wonders!

Ben Indick writes – “One of my disenchantments with fandom (I have been 98% gafiated for some time) has been the buck chasing, the self proclaimed prodom, semiprodom, demisemihemiprodom, etc. I really have nothing against fandom—just the blowhards and tinhorns who despoil it.”

And Donn Brazier writes – “Since I’m an old timer and grew up in FIRST FANDOM with the hekto and ditto publications (and even had one of my own) the appearance of the generally “purple monster” gives me a nostalgic thrill. I have had, or still have (underlined) the following hekto outfits. A cookie pan filled with gelatin/glisterine of my own mix, a teacher’s table flatbed duplicator with detachable film/gelatin, a huge metal stand equipped with a long roll of gelatin film, and a “spirit duplicator.” Production control is the bugaboo of the process. Colorful art and visual experimentation is the glory. Let us not forget short-print-run-only capability. Did you buy a commercial gelatin mix? My first mix, on which FRONTIER #1 was printed, was made of glycerine water and some boxes of orange jello. I got 30 pretty good copies. May Strelkov even boils up bones etc. for her mix. May I ask where you get ink for color—or did you trace through various colored stencils? It’s almost impossible to get ink anymore. Long live Hekto, Hecto, Ditto, Purple Monster, etc.”

Eric replied – “With all those hectos it’s no wonder you gafiated for so many years. CHARM and most of GROGGY were printed on a BEARS hector kit whose pitiful supply of colored carbons I augmented with ditto masters.”

There you have it, the trials and tribulations and joys of publishing a hector zine. Seldom done nowadays.

Note: According to the Evans-Pavlat Index, Brazier’s FRONTIER #1 was published in July of 1940. There were seven issues in all, ending in January of 1942.

Another note: Mae Strelkov (born in Russia) was a woman who ran a cattle ranch in Argentina late in her life. Her landscape hecto artworks, (utilizing gelatin rendered from dead cattle) were considered masterpieces. I used to correspond with her. Very tough lady. She was firmly convinced that the last generation of manly men fought in WWI. All generations of men since were a bunch of wimps. They certainly were compared to her. Kept her Gauchos firmly under control. A delightfully outspoken lady. Definitely a character.

BY THE WAY:

You can find a fantastic collection of zines at: Efanzines

You can find yet more zines at: Fanac Fan History Project

You can find a quite good selection of Canadian zines at: Canadian SF Fanzine Archive

And check out my brand new website devoted to my OBIR Magazine, which is entirely devoted to reviews of Canadian Speculative Fiction. Found at OBIR Magazine

And then check out my newest new website, devoted to my paying market SF&F fiction semi-pro zine Polar Borealis, at Polar Borealis Magazine

*Editor’s Note: Susan Wood revitalized the Club House column in Amazing Stories magazine during the Ted White era; it introduced many readers to fandom and fanzines, including yours truly. You can see her fanzines here, and read more about her here.

Thanks for the wonderful article on my adventures in hectography. Seeing my old fanzine Groggy written up in Amazing Stories may be the highlight of my faanish career. As I said in that ancient editorial you quote, I never aimed to win the general approbation of fandom or a FAAn award, buy I rather hoped, over the years, that some such recognition might find me anyway. It never did. However, this feature is more fitting than an award would be since I discovered fanzines through the Clubhouse column in this very magazine back in 1972.

By quoting me and my correspondents you captured the feel of the zine even after nearly forty years. Groggy was never intended to be an enduring work of art. I never worried about trying to meet some supposed “standards” set down by the self-styled cognoscenti nor did I model my zine after classic faanish zines of the past. To me the fun of fanzines comes in spontaneously communicating with other fans. In doing your own thing.

My repro method involved placing all the colors on the hecto master so, oddly, the registration problems occurred during the drawing process rather than the printing. I penciled a drawing then taped the top of the drawing to my master. The different colored carbons were inserted, one at a time, face down between the two. Once a carbon was in place, I traced the appropriate part of the drawing with a ballpoint pen, pressing hard enough to push the carbon onto the master at the bottom of the “sandwich.” The trick was keeping the two sheets aligned since the paper with the pencil drawing tended to bulge, and tear and disintegrate as every millimeter was slowly worked over by the ballpoint.

The first four issues of Groggy — if I remember rightly — were done entirely on a hectograph. When I was able to afford a hand cranked spirit duplicator, like the hecto kit from Sears, I dittoed the text and added hecto illustrations later, accounting for the misalignment you noticed.

To the extent anyone recalls Groggy it’s because of its anachronistic repro method. But the method was happenstance. I did it that way because I desperately wanted to do a fanzine and couldn’t afford anything else. Today, with the Internet and ezines, fans no longer face a monetary barrier.

Eric Mayer

Uh, Graeme, that would be Allyn Cadogan, not “Allen”… she was quite the fanzine fan. I reviewed one of her zines back in the ’80s in Amazing the print magazine.