With the newest JURASSIC PARK upon us this month it’s a good time to take a look back at the original which introduced us not only to the idea of realistic dinosaurs living and breathing on screen but also to the notion that computer generated imagery could be both a major marketing and creative tool for big screen blockbusters. Years later George Lucas (who supervised creation of the dinosaur effects unofficially while director Steven Spielberg was in Poland filming SCHINDLER’S LIST) would state that it was seeing how well the animation worked in JURASSIC PARK would convince him he could create the world of the Star Wars Prequels he had always envisaged.

In the 22 years since the original JURASSIC PARK premiered its reputation has grown to become embraced as a blockbuster of the summer blockbuster mold (while it’s other two sequels, THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK and JURASSIC PARK III have generally vanished), a classic to be enjoyed through the ages, one of the few the 90s produced. That’s a bold claim, but how true is it?

In the 22 years since the original JURASSIC PARK premiered its reputation has grown to become embraced as a blockbuster of the summer blockbuster mold (while it’s other two sequels, THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK and JURASSIC PARK III have generally vanished), a classic to be enjoyed through the ages, one of the few the 90s produced. That’s a bold claim, but how true is it?

Let me state one thing up front: I’ve never been that enamored of JURASSIC PARK, though I should be. I look forward to big summer blockbusters as much as anyone – the original STAR WARS is my favorite film of all time — and I was a junior in high school the year JURASSIC PARK was initially released. If it wasn’t made for me, it wasn’t made for anyone.

The original dinosaur effects managed the incredibly difficult feat of living up to, if not exceeding the hype surrounding them and have held up extremely well over the intervening years as the 3D re-release of the film proved. That’s important as that was not only the element on which the film was sold but the primary one on which its reputation has grown over the years. To paraphrase a Superman ad, you will believe a dinosaur can roar.

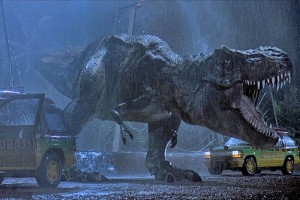

Not that that’s all the film has going for it, or else it may well have gone the way of James Cameron’s THE ABYSS (which has many of the plusses and minuses of JURASSIC PARK, but not all of them). Among his other skills, Steven Spielberg has always been a master of the set piece and the original JURASSIC PARK contains some of his finest work. The initial approach of the T-Rex up through Sam Neil’s race down a tree from a falling jeep are funny, suspenseful and thrilling in just the right measure, while also managing to get in some actually interesting character work. None other part of the film ever manages that level of craftsmanship again but it still has a lot going for it – the race over the electric fence and later the desperate attempt to escape the velociraptors after they infiltrate the main building. Each of these alone is almost worth the price of admission. [The later was so good in fact Spielberg aped it almost beat for beat 12 years later in WAR OF THE WORLDS]. In fact no other Spielberg adventure film (of which he made fewer and fewer in the years following) ever packed so much brilliance in one place again. They had their moments – the Normandy Beach assault from SAVING PRIVATE RYAN, the escape of the precog in MINORITY REPORT, the rocket car escape in INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL – but never so many in one place.

In many of both its initial reviews and newer ones from the time of the re-release JURASSIC PARK has been frequently compared with JAWS, presumably because they’re the only two films Spielberg ever made which had a killer animal as its antagonist. But that is not a particularly good comparison; JAWS is a horror movie – the creature is kept hidden until the third act, with much of the films propulsion coming from the beach people being attacked by an unseen assailant with no idea who will be suddenly yanked beneath the waves again. Suspense is its watch word. JURASSIC PARK on the other hand is an out and out monster movie, the creatures are front and center almost from the word go and remain so through the rest of the film (or at least seem as if they are, but more on that later), vehicles for thrilling action scenes which. JAWS signature image, the single fin approaching through the water, is also all you get of the shark until the third act; JURASSIC PARK’s image of the glass of water rumbling with T-Rex’s approach was used to similar effect in the film’s marketing, but the beast himself appears in all his glory just moments later. In that since its closest sibling is more INDIANA JONES than JAWS (Sam Neil’s escape over the pen wall with the jeep above being pushed ever closer could easily have come from a JONES film).

In many of both its initial reviews and newer ones from the time of the re-release JURASSIC PARK has been frequently compared with JAWS, presumably because they’re the only two films Spielberg ever made which had a killer animal as its antagonist. But that is not a particularly good comparison; JAWS is a horror movie – the creature is kept hidden until the third act, with much of the films propulsion coming from the beach people being attacked by an unseen assailant with no idea who will be suddenly yanked beneath the waves again. Suspense is its watch word. JURASSIC PARK on the other hand is an out and out monster movie, the creatures are front and center almost from the word go and remain so through the rest of the film (or at least seem as if they are, but more on that later), vehicles for thrilling action scenes which. JAWS signature image, the single fin approaching through the water, is also all you get of the shark until the third act; JURASSIC PARK’s image of the glass of water rumbling with T-Rex’s approach was used to similar effect in the film’s marketing, but the beast himself appears in all his glory just moments later. In that since its closest sibling is more INDIANA JONES than JAWS (Sam Neil’s escape over the pen wall with the jeep above being pushed ever closer could easily have come from a JONES film).

There is something it does share with JAWS, however; it’s conservation of visual effects ninjitsu. Though the set pieces are mostly magnificent it was the dinosaurs which sold audiences on the film in 1993 and the dinosaurs which continue to hold our interest so many years later. Ask someone at random what JURASSIC PARK means to them and the likely response is something along the lines of how good the dinosaurs looked and how they stand as a testament to how CGI should be used in a film, up to the point where it is a frequent comparison point when commentators note effects overdrive in a modern film. Both notes were made regularly by critics when they revisited the film during the release. And they are good points to make; it’s a rare film whose look maintains its power decades after its introduction given the rapid technological development the field has always gone through. But there are two important caveats to understand about that point – the dinosaurs are barely in the movie and most of the ones that are, aren’t computer generated.

One of the most well-known stories about the making of JAWS is of course that the shark itself did not work. Much of the power of the film comes from the lack of visibility of the monster doing the killing, increasing the terror (even once it is clear that it is a shark they are looking for) as there is no telling where it would come from or who it would attack. But, as the story goes, this was not the original intent, it was just a very successful side effect of the mechanical shark built for the film (affectionately nicknamed Bruce) refusing to function for much of the film, forcing Spielberg to shoot around it until the last 20 minutes when the machine finally makes a few above water appearances in quick cuts which also disguised the lack of realism in it.

One of the most well-known stories about the making of JAWS is of course that the shark itself did not work. Much of the power of the film comes from the lack of visibility of the monster doing the killing, increasing the terror (even once it is clear that it is a shark they are looking for) as there is no telling where it would come from or who it would attack. But, as the story goes, this was not the original intent, it was just a very successful side effect of the mechanical shark built for the film (affectionately nicknamed Bruce) refusing to function for much of the film, forcing Spielberg to shoot around it until the last 20 minutes when the machine finally makes a few above water appearances in quick cuts which also disguised the lack of realism in it.

As has been said, much of the strength of JURASSIC PARK is in how successful it is at achieving the very tall order of creating realistic dinosaurs. Such a tall order in fact that it was actually beyond the expertise of the visual effects wizards at ILM or special effects maestro Stan Winston. Winston could create highly realistic dinosaur pieces – heads, claws, feet – and even whole ones … as long as they didn’t have to move. The one thing he couldn’t do was create a dinosaur that could move under its own power. In a close up on dolly with a puppeteer moving its haunches up and down? Sure. In a wide shot maintaining its balance on its own two feet while walking? Not a chance. ILM could do that but under very specific limitations; even with a year of post-production they could only turn around a handful shots due to the immense rendering times and grappling with elements of computer graphics that are considered de rigueur today like ray tracing and surface texturing. Picking and choosing between the two techniques would allow Spielberg to get the effect he was after but it was clear that they would have to be used sparingly in order to a) be workable within the production time available and b) to hide their limitations. The result is a 120 minute dinosaur movie with just 15 minutes of dinosaurs in it (approximately 12% of the film) of which about 5 minutes (4% of the film) are computer generated. [Basically if you can see all of a dinosaur from head to feet in a shot, it’s CGI. If you can only see part of it, it’s a Winston puppet]. The material is well spaced out through the films’ runtime, however, hiding how little of it there actually is.

Unlike JAWS the makers of JURASSIC PARK knew about this situation before filming began and it was designed from the get go to hide both the defects in the individual effects and, more importantly, when the film was switching between them so as not to ruin the believability of the moment.

The primary method of doing so was to set most of the action in the dark and/or the rain, giving the physical and digital lighting technicians plenty of material for hiding the effects’ rough edges. Of the entire 15 minutes of dinosaurs only three full sequences happen outdoors in the cold light of day, one using a Stan Winston puppet and two others using computer animation. The first – a vista of a heard of brontosaurs eating – is the best of the films CGI and one of the best shots in the film, projecting the majesty, awe and realism of film dinosaurs (and, coincidentally what computer animation could achieve at its best). The second on the other hand – a shot of a herd of Gallimimus flocking towards Neil and his two young charges – is the worst, with very low resolution images and weak textures attempting to be masked by a lot of motion blur, all of which stood out notably when the film was remastered for a 3D and HD release. Fast motion and a large number of creatures pushed the animation team at ILM past its limits and though it was hard to tell at the time the shot stands out like a sore thumb now.

None of which can or does take away from the achievement the film made in its technical aspects – if it’s only noteworthy for its dinosaurs (and it is really only noteworthy for its dinosaurs) that is still worthy praise, on par with the original KING KONG’s stop motion gorilla. But when someone says JURASSIC PARK is the standard for how effects should be used in a film that must be taken to mean either designing the film in such a way that the effects are rarely seen straight on (either through lighting or by continually cutting from them – JURASSIC PARK does both), are primarily mechanical with CGI filling in only where the mechanics are impossible, or where the CGI shots are able to worked on for a long enough period of time that all of the kinks can be worked out. JURASSIC PARK, like a lot of successful films, falls into the perfect storm of being able to do all three of those things, but perfect storms by their nature don’t come about every day and designing a film to take advantage of one is designing a film that will never be made.

None of which can or does take away from the achievement the film made in its technical aspects – if it’s only noteworthy for its dinosaurs (and it is really only noteworthy for its dinosaurs) that is still worthy praise, on par with the original KING KONG’s stop motion gorilla. But when someone says JURASSIC PARK is the standard for how effects should be used in a film that must be taken to mean either designing the film in such a way that the effects are rarely seen straight on (either through lighting or by continually cutting from them – JURASSIC PARK does both), are primarily mechanical with CGI filling in only where the mechanics are impossible, or where the CGI shots are able to worked on for a long enough period of time that all of the kinks can be worked out. JURASSIC PARK, like a lot of successful films, falls into the perfect storm of being able to do all three of those things, but perfect storms by their nature don’t come about every day and designing a film to take advantage of one is designing a film that will never be made.

To drill down into that a bit more it’s helpful to note that the $65 million it cost to make JURASSIC PARK would be worth something like $175 million today, the bulk of which then as now went to the effects. That’s based not on the general rate of inflation or on the average modern cost of 15 minutes of visual effects but on the number of man hours it took to create those effects (379 people working for 12 months, about 300 of whom were on the CGI team). It cost about the same for 80 people to produce 10 minutes of mechanical effects as it did for 300 people to produce 5 minutes of computer animation; cost effectiveness is clearly on the side of computer animation once output can be increased, making mechanical effects as a primary tool more and more expensive and thus harder and harder to justify. Nor is any film which plans to put 25% of its effects budget and schedule into one shot likely to be greenlit, either.

What does that have to do with JURASSIC PARK as a masterpiece? Its two greatest claims to fame are its status as a breakthrough for computer animation and as Platonic ideal for how effects should be used in film. But it actually has less computer animation in it than most people realize (impressive though it may be) while the manner in which those shots were realized not only isn’t used by any filmmakers, including Spielberg himself, but probably can’t be out of sheer logistics.

So can a film still be a masterpiece if its pillars aren’t that solid? Probably, but that’s where JURASSIC PARK’s other problems emerge. Even the reviewers who have given the film stellar ratings usually point out somewhere in their pieces that it is due to the strength of the adventure elements and the effects which are so good they overpower the weak characters and no-frills plot. The acceptance of these weaknesses runs smack dab into that second pillar of greatness – JURASSIC PARK as pinnacle of a blockbuster because it uses its effects to service the story rather than become the focus of it. Looking at most reviews, from its original release and the recent re-visit, it’s clear that the positive notices are positive because of the effects and in-spite of the story and not the other way round.

In many ways, and not all of them good, JURASSIC PARK was a template for the type of big budget summer movies which would be made after it and throughout the 90s until basically the release of HARRY POTTER AND SORCERERS STONE in November 2001 and SPIDER-MAN in May 2002 switched focus inexorably to the modern blockbuster of today. But back in the 90s the plots revolved frequently around some sort of science fiction-esque catastrophe which only the smartest or the bravest could master, usually with some sort of action scientist in the lead or close behind: who becomes the mouthpiece for the primary warning/idea of the story: Sam Neil and Jeff Goldblum in JURASSIC PARK, Jeff Goldblum again in INDEPENDENCE DAY, Bill Paxton in TWISTER, Matthew Broderick in GODZILLA, Tom Hanks in APOLLO 13, etc. These all come from the JURASSIC PARK mold.

And Neil fits that mold to a tee in JURASSIC PARK. About half of his dialogue out of the entire film is a warning of some sort about why it’s a bad idea to build a fun park around dinosaurs, and when he’s not around to make that point Laura Dern and Jeff Goldblum pick up the ball. Considering the entire experience of the film is a hands on example of why it’s not a good idea at some point forcing characters to say it becomes moot but JURASSIC PARK won’t stop, it just doesn’t have anything else to think about. In order to facilitate that desire it has developed Richard Attenborough’s Jon Hammond (who, it must be said is similarly one-dimensional in the novel so perhaps it’s just the result of an honest translation) into a robot who can only repeat his desire to build a place where children can play with dinosaurs because it will be cool no matter what has happened to his grandchildren or anyone else stuck on the island when the dinosaurs get loose. The rest of the cast is placed in similar straightjackets, one note archetypes programmed to do the same thing over and over in order to eat up minutes before the dinosaurs can reappear. Wayne Knight is greedy, Samuel L. Jackson overworked and worried, Bob Peck just wants to make sure the raptors don’t get out of their pens. Only Sam Neil’s Alan Grant is given anything like a character arc as he forced to take on something he has been actively avoiding – being responsible for small children – and find out whether he might want to have some with Dern’s Ellie Sattler after all. Beyond being a pet theme of Spielberg’s which appears in many of his films it doesn’t seem to have much of a place in the movie it’s been shoehorned into – in fact the Grant/children bonding moments stick out like a sore thumb and are usually responsible for the film’s worst moments – but compared to the rest of the cast it’s something.

And Neil fits that mold to a tee in JURASSIC PARK. About half of his dialogue out of the entire film is a warning of some sort about why it’s a bad idea to build a fun park around dinosaurs, and when he’s not around to make that point Laura Dern and Jeff Goldblum pick up the ball. Considering the entire experience of the film is a hands on example of why it’s not a good idea at some point forcing characters to say it becomes moot but JURASSIC PARK won’t stop, it just doesn’t have anything else to think about. In order to facilitate that desire it has developed Richard Attenborough’s Jon Hammond (who, it must be said is similarly one-dimensional in the novel so perhaps it’s just the result of an honest translation) into a robot who can only repeat his desire to build a place where children can play with dinosaurs because it will be cool no matter what has happened to his grandchildren or anyone else stuck on the island when the dinosaurs get loose. The rest of the cast is placed in similar straightjackets, one note archetypes programmed to do the same thing over and over in order to eat up minutes before the dinosaurs can reappear. Wayne Knight is greedy, Samuel L. Jackson overworked and worried, Bob Peck just wants to make sure the raptors don’t get out of their pens. Only Sam Neil’s Alan Grant is given anything like a character arc as he forced to take on something he has been actively avoiding – being responsible for small children – and find out whether he might want to have some with Dern’s Ellie Sattler after all. Beyond being a pet theme of Spielberg’s which appears in many of his films it doesn’t seem to have much of a place in the movie it’s been shoehorned into – in fact the Grant/children bonding moments stick out like a sore thumb and are usually responsible for the film’s worst moments – but compared to the rest of the cast it’s something.

Compare this then with JAWS where the point of the movie isn’t the shark but the characters who are brought together because of it and how they react: Roy Scheider’s visceral terror that one of his sons may have been attacked; Robert Shaw and Richard Dreyfuss discovering, to their own great surprise, how much they have in common despite how different their backgrounds are in the films marvelous Indianapolis sequence. It’s a film where the effect is truly in service of the story because its real purpose is to get the characters together to interact with one another. Because the characters of JURASSIC PARK don’t do that, merely repeat the same emotions/lines over and over and over as they mark time for another thrilling dinosaur sequence. That is, the effects are entirely what the movie is about with even the filmmakers realizing how ancillary the rest was.

And then of course there is JURASSIC PARK’s worst failing – it has no ending. Sam Neil’s earnest paleontologist Alan Grant and the remaining group of survivor’s he’s been trying to lead to safety spend most of the last reel a step in front of the velociraptors who have broken into the main building and are relentlessly hunting them down. Finally, however, their luck runs out and they find themselves surrounded and about to be eaten. Like any good storyteller, Spielberg and his primary writer David Koepp (who would afterwards become Spielberg’s go-to person for adventure screenplays, working on MINORITY REPORT, WAR OF THE WORLDS and KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL, as well as co-writing the first SPIDER-MAN) tighten and tighten and tighten the screws, putting their characters into more and more impossible situations. And then, either because they ran out time or inspiration or both they reached a point where they had tightened the screws to the max and suddenly realized they were stuck. Rather than attempt to come up with a solution or re-think their approach to allow for some sort of way out Spielberg and Koepp and the rest of the brain trust opted to roll credits. After roughly 90 minutes of almost non-stop thrills (there’s a pause in the middle where Ariana Richards gets sneezed on by a brontosaurus the less said about the better) the surviving characters simply get into a jeep and drive away.

Compare such a moment to one of the other acknowledged masterpieces of 90s era summer blockbusters, TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY (there are, for my money, two and a half truly great blockbusters left to us from that decade: TERMINATOR 2, THE MATRIX and JURASSIC PARK). Like it’s brethren it is also a showcase for the cutting edge in what visual effects technicians could manage at the time (while much of the notice was for the liquid metal T-1000, much of the really landmark work in the film revolves around the more invisible processes of digital compositing and rotoscoping without which none of the modern effects era would exist).

However when the in-between moments come the film does not come to a screeching halt but rather stops to examine how the characters came to the places they are at and how they are slowly evolving going forward, from Linda Hamilton’s Sarah Conner rediscovering the necessity of connecting to other human beings to Edward Furlong’s John forgiving her for abandoning him to her struggle to even the cyborg killing machine himself coming to learn something about human nature. They are constantly evolving and changing across the narrative rather than simply repeating the same core of belief over and over and over again [you could actually play a drinking game based around how many times Knight says money, Peck says raptor or Dern says dangerous]. TERMINATOR 2 maintains attention and focus even when things aren’t blowing up. And when the climax is finally reached there are no easy escapes; instead they chip away and chip away at their foe (which is not the T-1000 but what the T-1000 represents: the future) until an act of sacrifice finally allows one clear shot at it.

By comparison JURASSIC PARK seems to have shrugged its shoulders and acknowledged that, as long as it got the dinosaurs working literally nothing else mattered. And to that extent the filmmakers may have been right. The original KING KONG suffers from many of the same problems and no one questions its place in the film cannon. And like its simian rival, JURASSIC PARK holds up many decades and viewings later. But for that very reason neither will ever ascend the plateau of the competitors that did, the JAWS and FRANKENSTEIN’s of the world. Can there be shades of grey within greatness? Maybe, but not at the very top. Either a film is a masterpiece or it isn’t and the fact that most references to the film include a major clause – ‘the dinosaurs are great BUT…’ – is a major clue which side of the line JURASSIC PARK falls on.

By comparison JURASSIC PARK seems to have shrugged its shoulders and acknowledged that, as long as it got the dinosaurs working literally nothing else mattered. And to that extent the filmmakers may have been right. The original KING KONG suffers from many of the same problems and no one questions its place in the film cannon. And like its simian rival, JURASSIC PARK holds up many decades and viewings later. But for that very reason neither will ever ascend the plateau of the competitors that did, the JAWS and FRANKENSTEIN’s of the world. Can there be shades of grey within greatness? Maybe, but not at the very top. Either a film is a masterpiece or it isn’t and the fact that most references to the film include a major clause – ‘the dinosaurs are great BUT…’ – is a major clue which side of the line JURASSIC PARK falls on.

If the worst that can be said about it is that it is an almost masterpiece, there are worst fates. If the last twenty years have proven anything, it’s that JURASSIC PARK will always be with us, dinosaur size warts and all.