Today we are joined by Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame author Kate Wilhelm. Kate helped blaze the trail for women in the science fiction industry, when she published her first short story in 1956. Her first novel, a mystery, found life in 1963.

From the beginning, Kate showed the world her natural storytelling would not be confined by labels. Across her career she has written fiction, classified as science fiction, fantasy, suspense, comedy, and mystery, to acknowledge only a few of the labels. Her imagination and creativity venture back and forth across the eroding lines of genre. She eternally dwells in the shadowed borders set by publishers and booksellers.

Kate’s importance to science fiction includes her contributions to creating the famous Milford and Clarion Writing Workshops. Not only did Kate help create these science fiction incubators, she sat patiently by, helping each little chick break free of its shell for more than twenty years. Her ability to evoke greatness from budding writers has helped produce some of the finest storytellers in the industry.

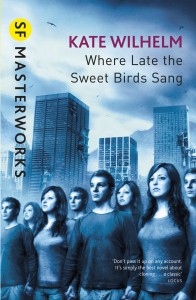

She even sketched out a concept for the Nebula Award trophy that today still remains true to her original sketch. Her novel Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang is considered by many to be one of the greatest science fiction novels ever written.

As proof of her amazing writing ability, Kate has been nominated for a staggering number of awards, including eighteen Nebulas. Her trophy case includes three Nebulas, two Hugos, two Locus, and a Jupiter Award amongst others.

In 2003, Kate was enshrined in the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame. The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) presented her with the Solstice Award for her significant impact in the science fiction and fantasy landscape during the first year of the award. If the world is a just place, perhaps one day soon she will be named a SFWA Grand Master. When not crafting a full length novel in her head, Kate spends her time calculating the fractal dimension of Julia Sets.

R. K. Troughton for Amazing Stories: Welcome to Amazing Stories, Kate. You grew up during World War II and witnessed humanity’s efforts to defeat evil. How did the war and the post-war world influence your storytelling and view of the world?

Kate Wilhelm: My thoughts about war were formed many years ago when I was a child growing up in Cleveland. I was a precocious reader, of course, as most writers attest to. I read everything, including newspapers and magazines that came into the house, and I was one of those fortunate children allowed to go to the Saturday matinees at the movie theaters. Not only Dick Tracy and the Lone Ranger, there were also newsreels. The news in print and in newsreels ran story after story about the ongoing Japanese/Sino war. I saw a newsreel in which Chinese peasants were fleeing on foot from advancing Japanese forces, and from the sky Japanese planes were strafing those people. The image still lives in my head. In the mid to late thirties an air show was held in Cleveland, and it was inevitable that everyone saw many aircraft performing maneuvers overhead. I saw a squadron of fighter planes doing intricate dances in the sky. When it appeared that four planes were heading for me in our backyard, I panicked, ran into the house, and I hid in a closet.

My father was in World War I. Two brothers were in WW II, one of them on a destroyer in the Pacific Ocean. Another brother was on the Dew Line in Alaska during the Korean War. My son was in Vietnam. And of course there were a number of non-war “incidents” such as the Panama Canal affair and other actions in Central America. None of them were called war, but a rose by any other name. . . All of my thinking life we have been at war, recovering from war, or preparing for the next war.

I also remember the fear mongering that seems to be a prerequisite for war: the Gulf of Tonkin incident; General MacArthur’s attempt to widen the Korean War in order to engage China; the domino effect if Vietnam fell to Communism; WMD, mushroom clouds and aluminum tubes . . . If only Eisenhower had had the courage to deliver his warning about the Military Industrial Complex on arriving in the White House instead of when he left it. I recently read an account of surfacing memos that reveal that then President Ford and Henry Kissinger talked about holding off bombing Cuba until after the presidential election. Fortunately for all concerned, Ford did not win and Jimmy Carter became president.

My first science fiction novel was The Killer Thing. A journalist interviewing me in Sao Paulo asked if it was a Vietnam protest novel. I said of course it was. My story, written in one sitting after I heard about Mai Lai in Vietnam, was titled “The Village.” I couldn’t get it published until Tom Disch asked for it for his anthology Bad Moon Rising.

My first science fiction novel was The Killer Thing. A journalist interviewing me in Sao Paulo asked if it was a Vietnam protest novel. I said of course it was. My story, written in one sitting after I heard about Mai Lai in Vietnam, was titled “The Village.” I couldn’t get it published until Tom Disch asked for it for his anthology Bad Moon Rising.

My hatred of war, revulsion of fear mongering, and disgust with the pandering to the worst instincts of human beings runs through a lot of my work. Most recently my novel Cold Case features an historian who has written a non-fiction book in which he summarizes the wars this country has engaged in from its beginning. It’s a long list and it does not shine a pretty light on us as a nation. As long as we have prominent people such as John “Bomb, bomb, bomb ____” (fill in the blank) McCain and Lindsey (They’re gonna kill us all!) Graham featured on talk shows week after week with the Greek chorus in full throat, it seems that my past experience with war is to be our future as well. I remember that our opening gambit in Vietnam was simply to send in a few hundred trainers and advisors after the French pulled out of what they correctly perceived as an unwinnable war.

ASM: In the 1950s, when you published your first short story “The Pint-Size Genie” in Fantastic, the science fiction industry was gearing up for the transition from the Golden Age to the New Wave. What was life like for you then as a trailblazing woman in a male-dominated industry?

KW: Too much has been written and is available now to go into a lengthy response to what it was like as a woman writer in the male-dominated field that science fiction was, and still is to a large degree. A couple of examples will do. Jim Blish advised me to stop writing for a year and catch up to what had been published in the field in the past. He called women’s writing the “dirty diaper and dishpan field of fiction.” To paraphrase Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady: “Why can’t a woman write more like a man.” I didn’t take his kindly meant advice. I read Thor Hyerdal’s book on crossing the Pacific Ocean in a bamboo craft, the Kontiki, in which Hyerdal stated that every day at sea he and his crew saw trash floating. I brought this up at a Milford Conference and Ben Bova looked at me pityingly and said, “Katie, do you really think we can pollute the entire ocean? Do you know how big the ocean is?” He didn’t literally pat me on the head, but the avuncular pat was there. I answered, “Yes.”

Roger Zelazny and I shared an Ace Double once, and his “book” sold more than my “book,” and he got a bigger advance than I did. We compared notes in those days. We, and by this I mean we women writers, knew that year-end anthologies, other anthologies, would have a ratio of 75% male writers represented, 25% women on a good day. We knew that far fewer women got reviewed than men, about the same proportion when the stars were in good alignment. And we knew that we received smaller advances in most instances. It’s just how it was.

Many established science fiction writers smarted because the genre was considered not quite respectable, not quite literary and worthwhile, not to be taken seriously, not to be respected, and was written for adolescents. Women science fiction writers know double what that feels like because the attitude extended, and still extends in many minds, to women writers: harmless, maybe cute, but not to be treated seriously, especially if they persist in writing in what should be a man’s field. It wasn’t only male writers, it included many fans who acted as if admitting women to the genre tolled its death. Three fans–we all know the type, large, unsocialized, hardly house-broken males–accosted me at my first science fiction convention. They advanced as I backed up, shy and intimidated, overwhelmed by the convention the way newbies usually are. They were aggressive and belligerent, making crude remarks about wannabe female writers, and one asked if I considered myself a better writer than soandso. It was years before I would consent to attend another convention.

ASM: As someone that surfed across science fiction’s New Wave, how would you characterize that period of the industry?

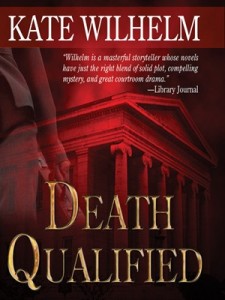

KW: Looking back at the late sixties, through the seventies, it seems clear in retrospect that we were in the opening phase of what may prove to be a paradigm shift. Monotheism, patriarchy, simple paternalism, authority of all stripes was being challenged. Feminism was forming itself into a coherent movement; minorities were demanding a voice. The Equal Rights Amendment was in the air. Massive protests, marches, sit-ins, riots were daily news fare. As a very small part of the greater movement, the New Wave was shaking up science fiction. Speculative fiction was code for try something different in style or context, or both. Literary values became a necessity, not an accident that occurred now and then. Instead of signaling the death of science fiction as had been predicted by the established, old guard pundits of the time, it was liberating. Writers were free to explore new things, new techniques, new markets even, and some who never had been identified as science fiction writers felt free to explore science fiction tropes. The umbrella had expanded, not constricted. Today we see speculative fiction, fantasy of all sorts, and hard science fiction all over the landscape in novels, movies, music, everywhere and nobody gives it a thought. It started back then and is continuing today. In the seventies and into the eighties, I was able to publish in Redbook and Cosmopolitan, even Family Circle, stories that would have been publishable in science fiction magazines. No one objected if the story involved immortality, space travel, telepathy, whatever. The first third of my novel Welcome Chaos was published in Redbook. It’s a novel that deals with immortality. No problem with the audience there. My first Barbara Holloway novel, Death Qualified examines chaos theory, telepathy, science gone awry, and not a single critic mentioned the crossing of two fields: mystery and science fiction. I don’t think anyone even noticed. It isn’t simply that lines are being crossed now; those lines have been largely obliterated. This breakthrough in science fiction started with the New Wave in the sixties and into the seventies.

KW: Looking back at the late sixties, through the seventies, it seems clear in retrospect that we were in the opening phase of what may prove to be a paradigm shift. Monotheism, patriarchy, simple paternalism, authority of all stripes was being challenged. Feminism was forming itself into a coherent movement; minorities were demanding a voice. The Equal Rights Amendment was in the air. Massive protests, marches, sit-ins, riots were daily news fare. As a very small part of the greater movement, the New Wave was shaking up science fiction. Speculative fiction was code for try something different in style or context, or both. Literary values became a necessity, not an accident that occurred now and then. Instead of signaling the death of science fiction as had been predicted by the established, old guard pundits of the time, it was liberating. Writers were free to explore new things, new techniques, new markets even, and some who never had been identified as science fiction writers felt free to explore science fiction tropes. The umbrella had expanded, not constricted. Today we see speculative fiction, fantasy of all sorts, and hard science fiction all over the landscape in novels, movies, music, everywhere and nobody gives it a thought. It started back then and is continuing today. In the seventies and into the eighties, I was able to publish in Redbook and Cosmopolitan, even Family Circle, stories that would have been publishable in science fiction magazines. No one objected if the story involved immortality, space travel, telepathy, whatever. The first third of my novel Welcome Chaos was published in Redbook. It’s a novel that deals with immortality. No problem with the audience there. My first Barbara Holloway novel, Death Qualified examines chaos theory, telepathy, science gone awry, and not a single critic mentioned the crossing of two fields: mystery and science fiction. I don’t think anyone even noticed. It isn’t simply that lines are being crossed now; those lines have been largely obliterated. This breakthrough in science fiction started with the New Wave in the sixties and into the seventies.

ASM: You witnessed firsthand the creation of the Science Fiction Writers of America (which later became the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America), and you helped design the Nebula Award handed out each year by the SFWA. Please provide us a glimpse of the circumstances surrounding these landmark events.

KW: When he was eighteen Damon left the tiny town of Hood River, Oregon to join a group of science fiction writers in New York, the Futurians. He was a real fan, had a fanzine, participated in fannish activities, and he began to write and get published. He told me that the Futurist group often talked of forming a professional organization for sf writers, but the efforts usually led to ingroup squabbles over who should be admitted, how it was to be run, who would be in charge, dozens of trivialities, in his opinion. Nothing was ever accomplished. Then, in the early sixties, he started to think about it seriously again. He said the only way it could be done was if someone just did it. It was his decision that only professional writers with two sales in recognized sf magazines, or sf novels with real publishers, would be admitted as members. There would be a monthly publication, which he called the Bulletin, and it could not degenerate into a fanzine with inevitable pie fights, but would have real news important to professionals: new sales, news of editorial shifts, market news, and most important to him, then and onward, careful appraisals of contracts and articles about how to negotiate good contracts, with a model contract as an example. There would be awards for short stories on up to novels and non-fiction, to be chosen by SFWA members. We discussed all of this endlessly, clarifying, modifying, adding details. The name of the award came along and it sparked an idea in my head. I drew a rough sketch of the Nebula Award: a black base, the void, with a crystal emerging, signifying creation, earth, or whatever crystals symbolize, and a spiral nebula hanging in space. All encased in a lucite block. Meanwhile, Damon gathered addresses of dozens of writers and wrote in essence: “I am forming the Science Fiction Writers of America organization. If you want to join, send me $5.00.” He posted the mailers and quite soon responses and checks flowed in. Some people accused him of being a dictator and he cheerfully agreed that he was. He asked Lloyd Biggle to be the treasurer, and we were both very relieved and happy that Lloyd said yes. Thus it all began.

KW: When he was eighteen Damon left the tiny town of Hood River, Oregon to join a group of science fiction writers in New York, the Futurians. He was a real fan, had a fanzine, participated in fannish activities, and he began to write and get published. He told me that the Futurist group often talked of forming a professional organization for sf writers, but the efforts usually led to ingroup squabbles over who should be admitted, how it was to be run, who would be in charge, dozens of trivialities, in his opinion. Nothing was ever accomplished. Then, in the early sixties, he started to think about it seriously again. He said the only way it could be done was if someone just did it. It was his decision that only professional writers with two sales in recognized sf magazines, or sf novels with real publishers, would be admitted as members. There would be a monthly publication, which he called the Bulletin, and it could not degenerate into a fanzine with inevitable pie fights, but would have real news important to professionals: new sales, news of editorial shifts, market news, and most important to him, then and onward, careful appraisals of contracts and articles about how to negotiate good contracts, with a model contract as an example. There would be awards for short stories on up to novels and non-fiction, to be chosen by SFWA members. We discussed all of this endlessly, clarifying, modifying, adding details. The name of the award came along and it sparked an idea in my head. I drew a rough sketch of the Nebula Award: a black base, the void, with a crystal emerging, signifying creation, earth, or whatever crystals symbolize, and a spiral nebula hanging in space. All encased in a lucite block. Meanwhile, Damon gathered addresses of dozens of writers and wrote in essence: “I am forming the Science Fiction Writers of America organization. If you want to join, send me $5.00.” He posted the mailers and quite soon responses and checks flowed in. Some people accused him of being a dictator and he cheerfully agreed that he was. He asked Lloyd Biggle to be the treasurer, and we were both very relieved and happy that Lloyd said yes. Thus it all began.

During this period Damon broke his arm. Frustrated and impatient, he had a handy-man friend rig up a system that consisted of a hook in the ceiling, with counter weight, rope and pulley, and a cradle. He could rest the heavy cast in the cradle and maneuver it up to the correct height to hold his hand in a typing position. The show must go on, all that. He was convinced that if the organization didn’t get off to a good start then, it might never happen and he was determined that it was going to happen.

The next step was to create the award I had sketched and for this he turned to Judith Lawrence and Carol Emshwiller. They both lived in New York with access to material and manufacturers. The hardest part Judith later told us was the floating nebula. They had to try various ways to form it so that it would keep its shape during the lucite pouring process. Since they were both geniuses, they made it work, and they created an object beautiful in and of itself, and too expensive for the fledgling organization, but Damon said, “What the hell. We’ll go with it.” We did, and I believe, to no one’s regret.

Damon said at the start that he would serve as president for two years, and we both thought that the election of a new president might be the deciding factor in whether the new organization would survive. Would anyone agree to put in the work required? Now, all these years later, the answer is clear enough. Although no longer president, Damon continued to work on the contract committee for the rest of his life.

ASM: Most science fiction fans can point to a single story, comic, or movie that hooked them on science fiction for life. What was your first exposure to science fiction?

KW: I was trying to read my way through the Louisville public library and one of the books I checked out was a thick anthology of science fiction stories. I never had seen any of the magazines and had no clue that the genre existed as a separate thing. I think now that the way our library was organized, with all fiction shelved alphabetically, with only short stories and a few mysteries off to racks of their own, influenced my own writing very much. Fiction was fiction, period. In my mind it’s still that way. A good story is a good story, period. Anyway, I had just finished reading a story I thought was really bad; I closed the book and said to myself, “I can do that.” I realized quite a bit later that I had given myself permission to write a bad story, but nevermind. I wrote a story in a notebook, the three-ringer lined paper kind, and I rented a typewriter. At least I knew it had to be typed double space, but that’s all I knew. I had never met a writer and there wasn’t a wealth of how-to books back then. I used the anthology for a clue about where to send the story and came up with Astounding Magazine. I sent off the story, and while I had the rented typewriter I wrote another story in the same notebook, copied it and this time sent it to Amazing. John Campbell at Astounding Magazine sent me a letter of acceptance along with a form to be notarized stating that it was an original story and I was the writer. I had no idea that that was not standard, and followed the instructions, and presently I received a check. I bought the typewriter with it. Meanwhile Amazing bought the other story, and that one was printed first, “The Pint Sized Genie,” but the Astounding story, “The Mile-Long Spaceship” was the first actual sale.

KW: I was trying to read my way through the Louisville public library and one of the books I checked out was a thick anthology of science fiction stories. I never had seen any of the magazines and had no clue that the genre existed as a separate thing. I think now that the way our library was organized, with all fiction shelved alphabetically, with only short stories and a few mysteries off to racks of their own, influenced my own writing very much. Fiction was fiction, period. In my mind it’s still that way. A good story is a good story, period. Anyway, I had just finished reading a story I thought was really bad; I closed the book and said to myself, “I can do that.” I realized quite a bit later that I had given myself permission to write a bad story, but nevermind. I wrote a story in a notebook, the three-ringer lined paper kind, and I rented a typewriter. At least I knew it had to be typed double space, but that’s all I knew. I had never met a writer and there wasn’t a wealth of how-to books back then. I used the anthology for a clue about where to send the story and came up with Astounding Magazine. I sent off the story, and while I had the rented typewriter I wrote another story in the same notebook, copied it and this time sent it to Amazing. John Campbell at Astounding Magazine sent me a letter of acceptance along with a form to be notarized stating that it was an original story and I was the writer. I had no idea that that was not standard, and followed the instructions, and presently I received a check. I bought the typewriter with it. Meanwhile Amazing bought the other story, and that one was printed first, “The Pint Sized Genie,” but the Astounding story, “The Mile-Long Spaceship” was the first actual sale.

I should add that at that time no bookstore in Louisville carried science fiction magazines, and the only place that did was a tobacco shop that was a front for a bookie. The Churchill Downs race track was in Louisville, after all. That shop had a prominent sign in its window: No Women Allowed.

ASM: How old were you when you wrote your first bit of fiction? When did you know you were born to be a writer?

KW: I told stories all my life and wrote stories through my high school years. I guess I had one in every issue of our high school newspaper. I was the editor with space to fill, so I dutifully filled it. I remember the night when I finished my first novel. It was very late, two in the morning, something like that. I felt elated: I could write novels as well as short stories! Immediately I put a new sheet of yellow paper in the typewriter and that night I wrote a complete story that had come to me before the novel was finished. I had kept putting it aside, fearing that it was a case of cold feet; what if I didn’t finish the novel, let myself be distracted by a tempting story, etc. etc. What if I couldn’t finish a whole novel? So the night I finished my first novel I wrote a story called “Jenny With Wings.” I was Jenny and I was flying.

ASM: You have read countless stories, both published and unpublished. What authors or stories would you suggest should be on everyone’s reading list?

KW: About the only advice I’d ever give to a writer concerning what to read is to read everything. For every one or two works in the field you’re interested in, read something very different from that field. For every two or three fiction works, read at least one non-fiction. Open your world door as widely as possible. You could be surprised by what you find out there.

ASM: Your novel Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang won the Hugo, Nebula, the Locus, and the Jupiter Awards for best novel and was nominated for every other prominent award. Many consider it to be one of the true masterworks of science fiction. For those that have not yet read the novel, please share with us what we can find beneath its cover and the origins of the masterpiece.

ASM: Your novel Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang won the Hugo, Nebula, the Locus, and the Jupiter Awards for best novel and was nominated for every other prominent award. Many consider it to be one of the true masterworks of science fiction. For those that have not yet read the novel, please share with us what we can find beneath its cover and the origins of the masterpiece.

KW: At the time I was thinking about and then writing Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang I was reading about children passing through Israeli kibbutzim. One study stated that the kids were exceptionally honest, dutiful, well mannered, obedient, all good qualities. But they were not very creative. I was also reading the Watson/Crick book on the double helix, and the implications their discovery posited, one of which was the possibility of cloning. There were articles about the growing global economies, the possibility of a global pandemic from a newly emerged disease as yet unknown, and a possible global shift in climate. The globalization of diverse societies was starting to get attention. All of those disparate articles and books played a part in my thinking through the novel. Add people to the mix and you have the story. Until you have the people, the characters, it all remains a set of interesting data, nothing more.

ASM: You helped create two of the most prestigious writing workshops in the industry and spent nearly three decades teaching the craft. Your book Storyteller: Writing Lessons and More from 27 Years of the Clarion Writers’ Workshop offers much of the wisdom you shared with your students. What tidbit of advice can you provide those budding authors who might be reading this interview right now?

KW: I put perseverance ahead of talent and intelligence even though they are both needed to some degree. I’ve seen highly talented people fail after a rejection or two, and I’ve known writers whose intelligence probably ranged in the genius zone who also failed, because they couldn’t deal with the rejections that new writers face. But with perseverance, less talented and intelligent newcomers often make it. Be stubborn and determined, keep at it, keep analyzing your rejections, keep writing. Don’t keep writing the same thing over and over if it doesn’t work. Try a different approach, try a different field even, but if you want to become a professional writer you have to keep writing for a very long time before you decide it was a mistake to go down this particular gritty path. And, of course, any teacher, mentor, writer who is asked for advice should always include the oldest bit of advice floating around: Keep your day job.

ASM: In your view, what is the most common mistake that new writers make?

KW: New writers make so many mistakes it’s impossible to boil it down to a single one, but bad openings is high on the list. A bad opening is muddled, details don’t match up, unknown characters are doing strange things for no reason that the reader can discern, and so on. Or the problem is that every character in the story sounds like every other character, or the speeches sound like the narrative. The list can go on, but what it comes down to is a lack of simple hard thought. At some point the writer has to draw back and question everything happening, everything said, every aspect. This can be before a word is written, my method, or after a draft, even after what the writer thinks of as the final draft. Back up and ask questions of the story. Why is she going down the dark stairs? If the answer is that the plot needs suspenseful action at this time, rethink the action. Taking the first easy answer probably will kill the story. How does he know something the reader doesn’t know yet? Again, if the answer is the first thing that comes to mind, it’s probably a bad idea. Give the characters some credit by not making them do stupid things because the plot demands it. Treat characters with respect and brains enough not to dash into a burning building because that would be an exciting plot twist.

ASM: You created InfinityBox Press as a response to the changing landscape of the publishing industry. Please tell us about the venture and what inspired its creation.

ASM: You created InfinityBox Press as a response to the changing landscape of the publishing industry. Please tell us about the venture and what inspired its creation.

KW: There was a time when writers and publishers and editors all wanted the same thing, good fiction, and they worked together to make it happen. There were twenty or more very good, respectable publishing houses with a variety of editorial voices. Even if editor A rejected you, editor at B might not, or C, D, and so on. No one at the top set the tone of multiple houses. Then corporatism moved in, conglomerates formed, the big cats ate the little cats, and writers became a necessary evil. Today there are five major publishers and although there might be a number of different imprints, they have to fit under the same corporate umbrella. It appears that to the head cheese writers are a burdensome bunch of pesky nuisances with demands that publishers no longer feel obliged to listen to. Contracts, written by corporate attorneys, regressed to a point where there was little or no negotiation possible because the power lay in the corporate headquarters and the bottom line was the only important consideration. I’m talking about novel publications primarily, not the short story magazines. The book publishers rewrote clauses concerning reversion rights, about ownership of copyrights, in such a way that writers who signed on had to agree that for ten years or even longer the publisher held the electronic book rights, with little recompense to the writers, half of the half compensation that paperback rights have routinely granted. In some cases even less than that. With no warehouse costs, no shipping costs, returns, and so on, the cost for producing an ebook is really negligible after the initial investment for routine editing and formatting for electronic publication. After that, a push of a button is all that’s needed to send a book to a reader. Why shouldn’t at least half of the income generated benefit the writer, as is the case of paperback clauses? I rejected such a contract, not over the advance, as I’ve said before, but about the ebook rights. I started Infinity Box Press as a consequence of a bad, non-negotiable contract. I’m old enough not to have to worry about ten years down the line, whether I could have gotten rights back at that time. I pity young writers facing this today. As Elizabeth Warren states over and over about the economy in general and student loans in particular, (I’d add publications to her list): the game is rigged, and not rigged in favor of the ones who make it possible in the first place.

ASM: Fans of your science fiction may not be familiar with your amazing mystery novels. Your popular Barbara Holloway novels have a foundation tied to Chaos Theory. For those not familiar with Barbara Holloway, please tell us a bit about her and the many wonderful novels where she comes to life.

KW: In the mid seventies I was called for jury duty. Here in Oregon at that time one served for a month, not necessarily being empaneled every day, but available, on call. It happened that I served on six juries during my month. I got a really good look at what happens at trials, how the judges behave, the attorneys, and of course the jurors. It’s really true that some jurors go into the back room with the firmly held notion that the defendant is guilty or would not be on trial. Some believe no police officers would testify to anything but the exact truth of the situation, that personal bias would not enter into such testimony. And so on. It was eye opening. After that month I put the whole experience aside, interesting, glad I had the opportunity to observe it all, and happy to be relieved of that particular duty.

Then, one day Barbara Holloway came to visit in my head. Characters do that for me. I didn’t have name for her, not a clue about who she was or what she did for a living, anything. But she was interesting to me. A strong woman, yet vulnerable in certain ways, intuitive but strongly rational as well. I visualized her in several scenes that invited other scenes and I knew she was going to be a lead character in something without any idea yet of what that something was. At the time I was fascinated by the Mandelbrot images, the Julia sets, how mesmerizing they were as we generated them on our own computers. And I had just read Glick’s book on Chaos Theory, and mused about how the connectedness of everything was evoked. The Butterfly Effect–a butterfly in China, tornado in Kansas sort of thing. Barbara could illustrate that, I realized. She would come to see connections that few others perceived. And lo and behold one morning I woke up knowing she was a defense attorney, that the older man in her life was her father, and their relationship was special. After that it was a matter of a good bit of research about the law, gathering the scenes in my head in some kind of order, filling in the blanks, telling a story about a woman who intuitively knew that the law she served and justice didn’t always fit hand and glove. My jury duty turned out to be most helpful. The novel is Death Qualified.

It was intended as a stand alone novel. I had not given a thought to a series until after a trip to Ireland when a girl of seventeen told me how her younger but bigger brother was brutalizing her and neither parent would or could intervene. She had seen her mother being brutalized by her father all her life and said there was no way her mother could escape because of the culture in Ireland; the church, family, neighbors all would ostracize her if she left and she had no resources of her own. It was infuriating and maddening to listen to that girl and witness her despair. On returning home, a second Holloway novel began to shape itself and I knew I had to write about women caught in that particular misogynist trap of fear, despair, torment. I realized that in Barbara Holloway I had a character who could put a personal face on so many social problems, one who could strike back against social injustice. A series began with the second book, not the first. That one was The Best Defense.

It was intended as a stand alone novel. I had not given a thought to a series until after a trip to Ireland when a girl of seventeen told me how her younger but bigger brother was brutalizing her and neither parent would or could intervene. She had seen her mother being brutalized by her father all her life and said there was no way her mother could escape because of the culture in Ireland; the church, family, neighbors all would ostracize her if she left and she had no resources of her own. It was infuriating and maddening to listen to that girl and witness her despair. On returning home, a second Holloway novel began to shape itself and I knew I had to write about women caught in that particular misogynist trap of fear, despair, torment. I realized that in Barbara Holloway I had a character who could put a personal face on so many social problems, one who could strike back against social injustice. A series began with the second book, not the first. That one was The Best Defense.

ASM: You are a member of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame and have received the prestigious Solaris Award from the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. Looking back at your career so far, what pushes the biggest smile across your face?

KW: I never felt better about any award, any honor, anything from the outside than I did the night I finished my first novel and absolutely knew I was a writer. No more uncertainty, hesitancy, self doubts which had plagued me. I was a writer. Nothing has topped that feeling of elation from so long ago.

ASM: Your husband, Damon Knight, was one of the giants in the science fiction industry. Please provide a brief character sketch of this legendary figure.

I can’t write a brief sketch of Damon–excellent writer, editor, critic, and teacher; iconoclast, perfectionist, both naive and worldly at the same time, introvert and narcissist, egocentric, husband, father, grandfather. The man I loved from when we met until he died. Complicated.

ASM: Over the years you have interacted with fans and authors on many levels. How do you see the importance of the relationship between fans and authors?

KW: We, as a couple, never were involved in fandom to any extent. Damon was as a very young man, but not later, and I never even met a fan until a fateful encounter in Philadelphia at my first convention. When we married he had three children and I had two. A few years later we had a son. So, six children in the family! We became involved with the Clarion Science Fiction Workshop, and he was very involved in SFWA. It didn’t leave much time for conventions or interactions with fans. Besides that, neither of us was very good in crowds, with strangers. Someone remarked on finding me at a convention standing off to the side chain smoking. Probably an apt description. I’m really much better as an observer than a joiner.

ASM: Famously you like to create an entire story in your mind before typing it out on the page. What tales are you weaving together that your fans might see from you in the future?

KW: As for what I might be mulling over to write, I draw a blank. I’m making a slow recovery from a spinal fracture, and my head is blissfully empty at the moment. But even if I knew I probably would not discuss it simply because I never did in the past, and old dogs, new tricks kicks in. Actually I seldom knew what I would tackle next until things began to coalesce in my mind and those things quite often reflected what I had been interested in, reading about, learning about. My recall is fairly good and to the best of my knowledge I never in my life said something to the effect: I’m going to write a science fiction story, or a mystery, or a comic novel. I seldom even knew what to call anything I was writing until it was written and, more often than not, I’ve let others decide to attach some kind of label. I’ve been thinking a lot about global climate change, GMOs in agriculture, ebola, things that I imagine most sentient people are concerned with these days. Will any of this be part of my next work? I have no idea.

ASM: Thank you for joining us today. Your keen mind and boundless heart have helped shape science fiction into the industry that we all know and love. Your legacy will continue to bear fruit for generations to come.

(Editor’s note: for more Kate goodness, a brief video can be found here)

R.K. Troughton works as an engineer, developing tomorrow’s high-tech gadgets that protect you from the forces of evil as well as assist your doctor in piecing you back together. His passion for science fiction and fantasy has been fed through decades of consumption. He is the author of numerous science fiction and fantasy screenplays and short stories, and his debut novel is forthcoming. His articles appear every Wednesday morning on Amazing Stories.