The Moon is popular these days: you can see posts and pictures about Apollo 11 pretty much everywhere on the web, 45 years after. A good time to think about our favourite – and only – satellite. There are a few interesting things worth mentioning, even though some of them are well known. Its creation, for a start. According to the leading theory, the Moon was formed by giant impact, when, soon after the solar system’s formation, something as big as Mars slammed into Earth. The two have therefore approximately the same age, and the same composition. It’s not a mystery either that a “dark side of the Moon”, songs apart, doesn’t exist. It’s that we can see just one face – and this is not due to the lack of light. The Moon is tidally locked to Earth – and its rotation matches its orbital period: end of the story.

Size too is somehow remarkable. The Moon is quite big for being a satellite, in absolute (it’s the fifth by radius in the solar system) and in relative terms (it’s the largest in comparison to its planet, at least if we decide that Pluto should not deserve that status). Other things are spookier. It’s less known, for instance, that there were plans to nuke the Moon – the so-called Project A-119 was developed by the U.S. Air Force in 1958, describing how to detonate a nuclear device on the Moon’s surface – and even a super-secret project for actually populating it with military bases. No, it’s not one of Heinlein’s books. The US government has recently declassified some documents, reporting all the details for a manned outpost on the Moon back in the ’60s. CNN and other outlets have described the whole story, so I won’t repeat it here. But I do advise to go and check the NSArchive Project Horizon I and following documents. They make a fascinating reading.

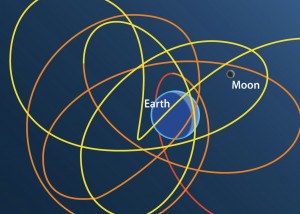

Bases aside, there’s one thing that is even weirder. The Moon might not be Earth’s only satellite, after all. Or is it? That moon counting changes is not a novelty. On July 15, 2014 we are at an overall number of 177 official moons. Mars has two moons, Jupiter has 67, Saturn 62, Uranus 27, Neptune 14 – and you can check out the updated statistics at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. But the story is more complicated when it comes to the nature of satellites. What NASA website reports are natural planetary satellites, not other kinds of objects. And you may find a few of them orbiting the planets of the solar system, Earth included. First of all you, have the quasi-satellites – asteroids orbiting our sun that sometimes cross Earth’s orbit. The most famous of them, discovered in 1999, was a tiny asteroid (around 3 miles of diameter) named 3753 Cruithne, with an orbital period of 770 years. Caught in the Earth’s gravitational grip, Cruithne is likely to stay around for 5,000 years. At least.

While famous (it appears in Stephen Baxter’s novel Manifold-Time, a Clarke Award nomination in 2000), Cruithne and the rest of quasi-satellites are by no means alone. Astronomers have also identified other bodies called minimoons. These are asteroids orbiting the sun somehow captured by Earth’s gravitational pull and that become Earth’s own satellites. These temporary moons will orbit our planet following complicated paths for a while, before eventually breaking free and resuming their sun-orbiting behaviour.

Back to the Moon. If you are, like I am, fond of geography, data collected by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and available on NASA website present a really accurate maps of its features. Some of the videos cover beautiful spots such as Tycho Crater, Taurus Littrow Valley (where Apollo 17 landed) and even footage of its far side. Oh, and the moon is slowly getting away from us, a few inches more each year. According to astronomers, it was about 14,000 miles from Earth when it formed. Nowadays it’s at more than 280,000 miles. You better have a good look at it while you can.