“There is just one reality left, we are here and it is now.” Wise words spoken by astronaut of the future George Taylor (Charlton Heston) upon arrival on a mysterious planet one may have reason to suspect is inhabited by apes. Taylor doesn’t know that yet. He and his fellow surviving crewmembers, Landon and Dodge, having crash landed in a desert lake, wander across the barren landscape in search of life, Taylor spouting off about the worthlessness of mankind and his hope of finding something better somewhere in the universe. He spots Landon erecting a little six inch high American flag—and bursts out laughing.

If you’ve ever watched The Twilight Zone, it’s easy to see the hands of Rod Serling all over this movie. Serling wrote numerous drafts of the script, based on Pierre Boulle’s novel, though Michael Wilson re-wrote some of the dialogue (it would seem few participants agree on just how much; most of the film’s cheesier lines have been attributed to him, at any rate), and the most famous part of the movie, its ending, is all Serling’s.

If you haven’t seen Planet of The Apes, and if you don’t know how it ends, you should stop reading now (not sure how many humans fall into this category, but one never knows). Watch it and return. Spoilers aplenty follow.

Boulle’s book tells the story in a very different manner. It begins with two astronauts finding in space what is essentially a ‘manuscript in a bottle,’ i.e. an account by another astronaut of his trip to the mysterious planet of the apes. The surprise ending in the book is not that the planet of the apes was Earth all along, it’s that the two astronauts reading the account turn out themselves to be—chimps! Bam! The apes are everywhere!

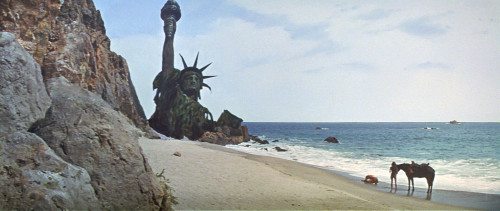

Such subterfuge is easy in a book, less so in a visual medium. Serling first tried an ending where, in the cave at the end, a movie made by the U.S. Air Force is found showing the nuclear annihilation that consumed mankind. Next up he settled on the Statue of Liberty’s crumbling remains found in a jungle, and tweaked it from there. A very Twilight Zone kind of twist. All this time we’ve been told the astronauts have flown so far from earth, and so fast, almost the speed of light, that the earth has aged almost two thousand years while they’ve only aged eighteen months. Surely they are on a far-away, mysterious planet, where of all the mad realities imaginable, apes enslave humans.

Nope, they’re home. They destroyed themselves. Serling didn’t have the happiest outlook on humanity’s foibles. You could summarize pretty much every episode of The Twilight Zone as “mankind laid low by his hubris.”

I’m not sure the twist ending wouldn’t be obvious to a modern viewer, but it certainly caught audiences in ’68 off guard. The movie caught everyone off guard. It was a huge success and spawned more sequels than you can shake a stick at.

I, however, am I professional stick-shaker, and as such will be watching every Apes movie there is, leading up to the latest one coming out this summer. Because why not? Someone has to. I haven’t seen the Apes sequels since I was a kid. Will I be surprised by their genius? Appalled by their wretchedness? Join me and find out!

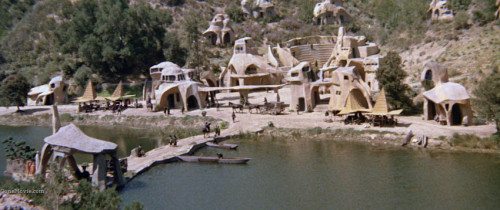

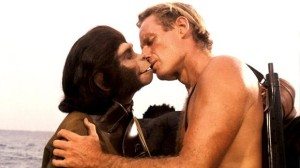

One thing I know for sure: the original Planet of The Apes is a winner. It’s directed with just a touch of flair by Franklin J. Schaffner (who would go on to direct, most famously, Patton, Papillion, and The Boys From Brazil), and acted with cigar-chewing abandon by Charlton Heston, who’s surprisingly convincing as a cynical misanthrope. The budget wasn’t huge, but the ape effects, by John Chambers, are strangely convincing, even today. They’re both fake and totally plausible. As for the primitive ape backlot—um, city, it’s less successful, but the story’s good enough that it’s not too distracting. Serling’s origial script called for a far more technologically advanced ape society, one too expensive to realize, the studio decided.

The story isn’t much, but it doesn’t need to be. The movie is concerned with one thing: to knock we humans off of our mighty, self-constructed pedestal, and force us to look at our nutty world in a new light. Taylor is captured, locked in a cage in a laboratory, given a lovely primitive human girl to mate with (Nova, he names her, played by Linda Harrison), and almost dissected before making his escape. He doesn’t spend any time reflecting on how the apes in charge of this world are as evil, prejudiced, and short-sighted as the humans on his own, but the ending sums it all up with his famous line: “We finally really did it. You Maniacs! You blew it up! Damn you! God damn you all to hell!” Now that’s a line to go out on.

If there’s one oddly ignored logical flaw of the movie, it’s that the apes on this far away mystery planet speak English. Even being on Earth, it’s awfully dodgy. Languages don’t remain static for two thousand years. But realism isn’t what this movie is after. It’s a parable, and as such, logical language lapses may be ignored.

1968 was a good year for science fiction, with 2001 opening only two months after Planet of The Apes. It’s no wonder the sci-fi of the ‘70s was largely known for its big ideas and social consciousness. Until Star Wars came along, that is. Planet of The Apes is obviously not Kubrick, but it accomplishes something equally spectacular, something too often underappreciated: it tells a simple story that’s exciting, original, and thought-provoking.

The Going Ape series:

- Beneath The Planet of The Apes

- Escape From The Planet of The Apes

- Conquest of The Planet of The Apes

- Battle For The Planet of The Apes

This article (and subsequent Ape essays) originally appeared on the cinema blog Stand By For Mind Control, where editors Sean McPharlin (aka the Supreme Being) and Zack Kushner (aka the Evil Genius) cover the breadth of cinema in their inimitable style. They are thrilled to be contributing discussions of genre cinema to Amazing Stories.