A couple of years ago, Charles de Lint gave a reading in Toronto from his current young adult novel. He began by saying that he was surprised that his publisher allowed some of the language and situations that he had put in the book, which he felt were quite adult.

A couple of years ago, Charles de Lint gave a reading in Toronto from his current young adult novel. He began by saying that he was surprised that his publisher allowed some of the language and situations that he had put in the book, which he felt were quite adult.

If situation and language are not toned down for it, what does the term “young adult” actually denote (other, perhaps, than an opportunistic marketing niche)? As far as I can tell, the main feature of young adult literature is that the protagonist, the story’s point of view character, is a teenager (although this would make it something of a misnomer, since adulthood doesn’t legally start until the late teens in most jurisdictions and arguably doesn’t start emotionally and intellectually until well into one’s twenties). The congruity between the two categories would suggest that books designated as “young adult” should be reviewed with the same criteria as books for adults.

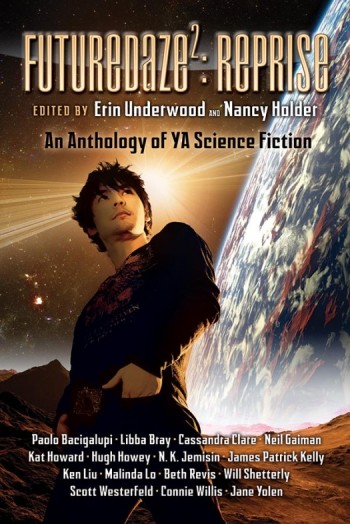

FutureDaze2: Reprise, an anthology of young adult science fiction edited by Erin Underwood and Nancy Holder validates this approach: it’s great reading no matter what age group the reader belongs to.

The anthology starts strong with Neil Gaiman’s How to Talk to Girls at Parties Every anthology should start with a Neil Gaiman story. The story of a shy boy who gets dragged by his more outgoing friend to a party that neither of them bargained for is imaginative and amusing.

This is followed by three post-apocalyptic stories, a sub-genre that has never appealed to me. The stories are well written, and have their points of interest: Malinda Lo’s Good Girl, for example, plays with the stereotype of the submissive young Asian woman, while Connie Willis’ A Letter from the Clearys uses repetitions of the phrase “Paranoia is the number one killer of…” to indicate how shallow the main character’s understanding of the adult world in which she lives truly is. Those who enjoy dark fiction will certainly enjoy these stories.

Then comes Paolo Bacigalupi.

Bacigalupi has a tendency to put his female protagonists through horrendous physical abuse, often involving forced physical changes and ugly mutant forms of sexuality. Such stories culminate with the protagonist engaging in an act of violence which, I assume, Bacigalupi intends as a catharsis for the reader which redeems the narrative. For me, the abuse was so terrible that the payoff didn’t work in the novel The Wind-up Girl, and it doesn’t work here in the short story The Fluted Girl.

If there is a saving grace to the story, it is that the fluted girl plays a game where she hides from everybody in the house for a little while before she has to meet with people. It may seem a childish prank to some, but it is the only act of defiance allowed to her within the life she has been given, and it does invest the character with a sense of agency. She is not entirely a passive victim. Unfortunately, what is being done to her is too icky for this to redeem the story.

Had I been reading the anthology purely for pleasure, I probably would have stopped here, which would have been a shame because I would have missed several excellent stories.

Libba Bray’s The Last Ride of the Glory Girls, for instance, is a kind of future steampunk story: it takes place on a colonized world where future technology meets western frontier life. It reminded me of Firefly in this way. I must admit that I have always been leery of mixing western and science fiction tropes, but, like Firefly, this story won me over with engaging characters and clever storytelling.

This was followed by one of the highlights of the collection: Stupid Perfect World, by Scott Westerfield. In a world where technology has solved every problem, high school students have to take a class in Scarcity: for one month, they have to experience something that people would have experienced in a world of scarcity, a world before the machines could fix any human problem, a world like today. Some of the characters choose to experience obvious things (such as the common cold), but the main character chooses something unexpected: he chooses to need sleep.

It’s a great concept, wonderfully realized.

FutureDaze2: Reprise ends with another pair of strong stories. Ken Liu’s The Veiled Shanghai retells the story of The Wizard of Oz through the filter of Chinese history. It’s a fertile mix of two very different mythologies.

I Never, the final story in the anthology, isn’t, strictly speaking, speculative fiction. Cassandra Clare’s story is just about a bunch of kids getting together for the weekend at a cottage. They share many common interests with other teenagers: they are horny and desire to get more than a little shitfaced. But, they’re not just any kids: they’re cultural geeks. As with many young adult stories, acceptance is an important theme in “I Never,” a theme which seems especially relevant to these kids, all of whom have a keen sense of being outsiders to the wider teen culture. Despite its lack of a speculative element, the story ends the anthology on a sweet grace note.

Every literary genre and sub-genre has a built-in thematic that is always there regardless of whether or not the author chooses to bring it to the surface. With young adult fiction, the thematic involves young people trying to understand and negotiate both the social world they inhabit and the adult world whose rules are only partially known to (or understood by) them. Speculative fiction offers a new way of approaching this theme by having its young protagonists negotiate a world that doesn’t exist; in this way, it is a safe venue for teenagers to consider their own place in the real world.

All of the stories in FutureDaze2: Reprise explore how teenagers function in a world they only partially understand, some fancifully, others seriously, some with a light tone, others quite darkly. In one volume, they are very enjoyable.