A little while ago, I promised myself and my readers to have a look at fantasy art outside the—largely—European tradition. One danger of doing this is that I don’t know an awful lot about some of the traditions I hope to look at. Another danger is that unlike the unicorns and elves, the dragons, mermaids and witches which populate European fairy tales and fantasy literature, some of the entities I will be looking at are being venerated in a religious context to this day. The borders between fantasy art and religious art are very fluid, and it is quite possible that some of what I show and write—or the fact that I do it in this context—may offend some of my readers.

I ask pardon in advance: my aim is to broaden the spectrum of the art I look at in this blog, not to provoke or patronize. Anything that might offend you, please put it down to ignorance, rather than disrespect. And please feel free to enlighten me in the comments!

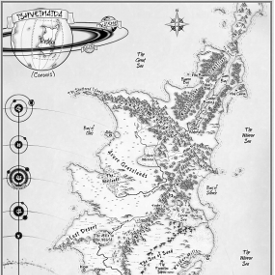

This is the fifth installment of my look at art inspired by the various Afro-American religions—Santería and Voodoo, as practiced in the Caribbean and the Bayou—and South American Candomblé and Umbanda, which I remember well from my teenage years spent in southern Brazil.

All these syncretic religions originate from African religious practices. African people were not only uprooted and forcefully resettled, they were also forcefully converted to Christianity — in most cases, Catholicism — and so they grafted their own deities on to Catholic saints.

The resulting religions and spiritual practices are alive and healthy to this day, and present a fascinating mixture of European and African influences. Although they are independent religious practices, they do share some of their main deities. The legacy of the Yoruba people is particularly prominent—a number of the main deities can be traced back to what is now Nigeria.

To finish off this series of posts, here is a selection of deities whom I have not yet introduced in one of my previous blogs. This is not to imply that they are less important or less venerated – just that I have found fewer pictures of them.

Nana, or Nana Buluku, is the oldest of the Orixas. She is originally a deity of the Fon people of Dahomey, who venerated her as the mother of creation. In Yoruba mythology, this is an aspect of Yemoja. In Brazilian Candomblé, she is called simply Nanã (grandmother), and depicted as a very old woman with a wide white skirt and a white headdress – a type of dress that is also often worn by women in the Northern Brazilian city of Bahia, where the influence of Candomblé is particularly strong.

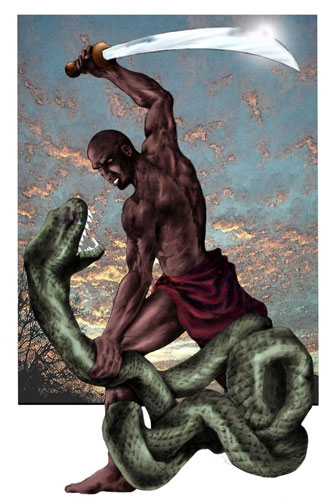

Ogúm (Ogoum, Ogun) is the male warrior god. He is also the patron of smiths, and presides over politics and truth (oddly enough!). In Candomblé, he is venerated as St George – the slayer of dragons – or sometimes as St Sebastian or St Anthony. His attribute is a sword or machete – and sometimes rum or tobacco.

Oxossi is the patron of the hunt and the forest. He is associated with abundance, food and energy, and patron of those seeking justice. He is a solitary figure, but he is friends with the caboclos (people of mixed European and native American origin in Brazil), and with the spirits of the forest. He is more important in Brazilian Candomblé than in other Afro-American religions, and does not appear to have a parallel in African religions – so, given his association with the caboclos, possibly his origins lie with the Brazilian rain forest and its people, and not in Africa. He is venerated as St Sebastian, and – not surprisingly for a hunter god – his attribute is the bow and arrow.

Another forest god is Osain – who can be male or female, and is a healer and keeper of the herbs of the forest, rather than a hunter.

The Ibeji are the sacred twins of Yoruba religion. Yoruba people have a particularly high rate of twin births, and so it is not surprising that they have a special deity for it! It is believed that twins share one soul, and when one of them dies, his or her soul is kept in a carved statue, which is also called Ibeji. They play a lesser role in Afro–American cults.

Another deity who takes on male or female form indiscriminately, is Oxumaré, the orixá of rainbows – also called the rainbow serpent. He/she also protects the umbilical chord, which in Candomblé, is buried with the placenta under a palm tree – a ritual that, incidentally, is also observed by the Maori people of New Zealand, and very important to their identity! The name is Yoruba in origin, but I wonder if the concept might be linked to Quetzalcoatl, the “Feathered Snake” of the Aztecs – or perhaps a similar deity native to Brazil?

Then there is Babalu Aye – orixa of infectious diseases and of healing, patron of smallpox, leprosy, influenza and AIDS. He is associated with the earth and all things earthly: the body, wealth and physical possessions. His appearance is that of a shaman – a witch healer – or a leper: his face is completely covered with a headdress, and he is hobbled by disease. His representation in Candomblé closely resembles certain traditional African masks.

Lastly, there is Eshu or Exú – also called Elegba, or Papa Legba In Haitian Voodoo. In New Orleans, he is Baron Samedí. He is the guardian of roads, particularly crossroads, and of travelers (and hence, of traveling musicians – he is the devil on the crossroads, to whom certain Blues musicians are said to owe their near magical skills). He also guides the spirits of the deceased to the other world, and thus is an incarnation of Death. He is a trickster, who likes to provoke people into thinking about their own narrow-mindedness and limitations. He carries a cane or a shepherd’s crook, and he smokes a pipe. He is a dandy in a top hat decorated with skulls, and has a most seductive smile.

All images are copyright the respective artists, and may not be reproduced without permission.