I can remember the time, and it was not very long ago, when professional artists I know had to come up with excuses to paint. Weekends, evenings—whatever they could scrounge in the way of free time—they devoted to their easels, reveling in the feel, the smells, the experience of PAINT. WHY? Because to make a living, they had to spend their working hours at their computer.

I can also remember the time, and it was not very much earlier than that, when collectors awoke to the fact that it really wasn’t possible, or necessary, to establish a gorgeous collection of art based solely on published illustrations in the science fiction and fantasy genre.

It is the confluence of these factors—artists still keenly desiring to paint, and collectors whose tastes ran to SF/F themes painted in illustrative style—that in the last twenty years has changed the face of collecting art in this genre.

Only a Generation Ago . . . For Artists

There was a time, believe this or not, when the best illustrators in the SF/F field wanted nothing more than to escape its constraints—if they painted at all, in their free time, they spent it painting in totally different styles, subject matter, dimensions. Like Walter Mitty, they might spend years leading secret lives—painting in “loose, expressionistic styles” totally unlike the illustrative works they were known for. Gary Ruddell (one-time Hugo Award nominee for Best Artist) was such an artist until the day he could escape the shackles imposed by publishers and become a “fine artist” for good. When these artists were in the mood to express themselves, trust me, the LAST possible choice for imagery would be science fictional. 🙁 And Ruddell is not the only artist who who felt that way. And even if they didn’t mind the subject matter, they hated being told how to paint it. They chafed mightily at the art direction.

Simultaneously, of course, there has always existed whole bunches of artists who absolutely LOVED the themes of science fiction and fantasy—and despaired when the 1990s wrecked their dreams of making a living from painting illustrations for books and magazines. I can remember vividly the talk Vincent DiFate gave at a SF convention sometime in the early 90s, which had as its focus “advice for aspiring artists wanting to enter the field of SF illustration.” His advice? “Don’t.” Don’t bother. You won’t be able to get work. The field is dying. Whatever jobs there are, are not even sufficient for established artists to survive on. “If you must go to school for an art degree, and want to earn a living after you graduate, make sure your education is heavy on computer skills; learn web design, graphic design.” Those in the audience frowned, and didn’t want to hear it.

Only a Generation Ago—For Collectors

When we started collecting the only place in the world where you could see unconventional, themes of “the imagination” painted in traditional styles was on the covers of science fiction and fantasy magazines and books. Period. And the only place you could buy them was at a convention, or by tracking the artist down. That’s how, and why, we became collectors of SF/F illustration art. It’s not that we didn’t look elsewhere for the kind of art we liked: we visited galleries, museums, outdoor art shows . . . for years. It wasn’t there.

Just as important, we realized that if it didn’t appear on a publication, it didn’t exist. Literally. It wouldn’t have been painted, it wouldn’t have come into this world, if a publisher hadn’t hired an artist to paint it. That was not only its raison d’etre, but in time, also gave it its cache. This is how, and why, Heritage Auctions advertises sales of Illustration Art. There are collecting fields devoted to it: children’s, westerns, “men’s mags”, pin-ups, gothics, noir.

And how did you build a great collection when hundreds of books and magazines a year are being published a year and you could have your pick of almost any or all of them? Easily. All you needed was a good eye, time, and a little money. With emphasis on the “eye” and (only in retrospect, of course!) “little” 🙂

And then came the day in the late 1990s when we looked at the walls and realized that we hadn’t bought anything “new” from artists in months. And when we thought about it, we agreed it was because the art wasn’t thrilling us like it used to. And much as we hated to admit it, it was because the covers of books and magazines were getting boring. It wasn’t the artists’ fault; it just wasn’t innovative any more. And we already owned “good” ones by all the major artists in the field, so we didn’t need more examples—and besides, they were leaving the field (and being joined by all the newer talent, it seemed), either to produce art that was digital, or tiny—paintings that appeared on card games we didn’t play and had no interest in. 🙂 And yet we still had the itch to buy art, and see what artists could do with stories we loved, and all of a sudden it came to me: why not challenge artists we knew to keep painting great ones, through a PRIVATE COMMISSION? Why not?

And that is how the Haggard Project came to be . . . and how we became unwitting pioneers in the newest of great ways collections are being built today.

Artists and Collectors Today

Yes, there are still paintings being produced for publication (though just a few) and there are collectors to buy them. But, unfettered by the constraints of publication and painting to “briefs” ordered by art directors, artists who have the desire to paint, and the skills and imagination to create images that we crave—are finding that it can be FUN—and just as self-expressive—to paint dragons and elves and BEM’s and scenes of mythical/mystical lands. On Spec. And what’s even more important: today’s art buyers are no longer defining themselves as collectors of illustration art . . . and are buying the art.

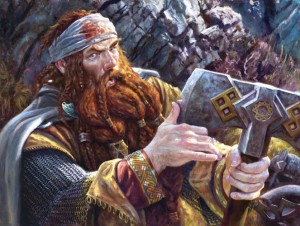

As Daniel Perkins, a self-described “young buck” of a collector (still in his 30s) puts it, “commissioning paintings gives newer artists a chance to “strut their stuff” by creating art which retains some elements of (commercial) commissioned illustration while venturing into “fine art” territory.” In other words, the imprimatur of publication and/or source (book, game, magazine) has given way to the strength of literary, film, character, or product association—and fans’ attraction to it. Just as we reveled in paintings that interpreted stories by H. Rider Haggard, younger collectors like Perkins are entering the market with dreams of art that captures the excitement of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. And are willing to establish collections built upon that single, and very satisfying, connection.

And what’s more, it’s art that can be expressive in ways that art “painted to sell products” cannot be: not just more graphic in terms of sex or violence, but “darker, more brooding themes and darker palette; less contrast; while still demonstrating the same skills in execution,” says Dan, and points to Vitale’s “Smaug and Bilbo” as an example, in his re-imagining of their encounter from Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

Dan readily admits that he, like many collectors before him, buys art for nostalgic reasons. “The paintings I have are very specifically books I’ve read, games I’ve loved, etc.” Unlike us, collectors who started off being attracted to the imagery, without regard to what author, story, publication or character was being depicted, Dan has “never commissioned anything or even has ever bought a painting, purely because I ‘liked it.'” (!) While he’s not averse to the idea that a painting may have come into existence for purely commercial reasons, he enjoys the excitement that follows from “letting go of your idea, and trusting the artist’s vision”

AS ALWAYS AND WILL BE: buying art “well” requires a good eye, time, and money. And it still is mostly found at conventions, and by tracking down artists 🙂

What is NEW: if you’re BUILDING a collection today, you’re probably not as impressed with “vintage” or “classic” or “pulp” SF/F art as I am. It’s not only expensive, and unfamiliar to you, it looks amateurish, crude and silly. Because, for the most part, it was. Today’s artist’s are much more skilled. What’s also NEW: you’re not going to be as driven by the idea of commercial publication as previous generations . . . mainly because your attachment to the art is not being driven by the covers of books and magazines you remember reading as a child, but rather the movies you saw, or the games you played; an association that is based on nostalgia of another kind. This leads to collecting of another sort: could be by author (Herbert, Dick, ERB, REH, Tolkien); book title (Dune, LOtR, Conan, Tarzan, etc), character or subject (dragons, cities of the future, Alien Greys, mermaids), or product (D&D™, or Middle Earth CCG art).

I could end this posting with the bad news: our choices, as collectors, and as artists, have narrowed. If we want to spend our waking hours looking at these kinds of original paintings, or painting them, it’s going to be up to us to make that happen. As an art buyer, you can either compete with collectors for the best in existing illustrative art on the secondary market or buy art that doesn’t come with a publication source as its pedigree. As an artist, you can either build a following for your fantasy and science fiction artwork that is independent of the exposure that comes through commercial assignments, or paint something else.

But, regardless of how you look at it, Isn’t it remarkable that at the end of the era of illustrative art (as we knew it) we have figured out a way to breathe new life into this collecting field?

Recent Comments