(This post is part of an on-going series that examines the short stories collected in The Science Fiction Hall Of Fame, a seminal anthology selected by the members of the Science Fiction Writers of America and edited by Robert Silverberg, SFWA President at the time of anthologizing. Previous installments can be found here.)

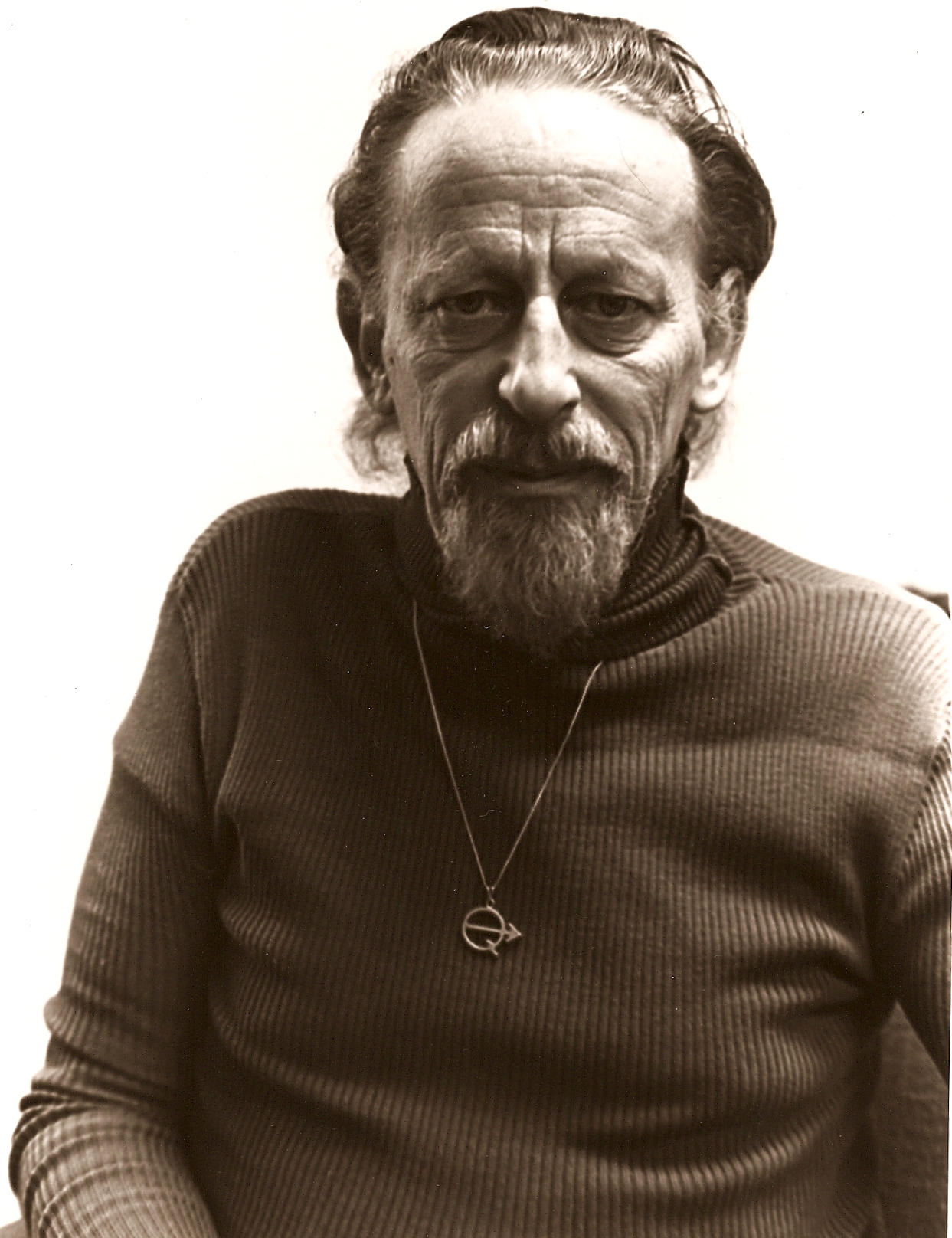

Theodore Sturgeon remains, to this day, one of those golden age SF authors that the word enigma best describes. Product of a tumultuous childhood and subject to a highly schizophrenic relationship with writing (long periods of silence followed by bursts of writing), Ted delved deeply into the human condition, exploring themes of sexuality, meaning, triumphalism, discrimination and more well before most of his contemporaries. More Than Human remains a seminal classic of transcendance; The Cosmic Rape remains a classic exploration of taboo themes; The World Well Lost and Affair With A Green Monkey are two of the earliest SF stories dealing with homosexuality and remain relevant today.

Sturgeon has had awards named after him and it is fitting that at least one of his stories should have been included in The Science Fiction Hall Of Fame.

That story is Microcosmic God and has remained one of my most favorite SF shorts ever since I read it for the first time in the anthology that is the focus of my attention here.

Imagine if you will the perfect story for an ambitious, scientifically minded, socially sensitive school kid to read when they are ten years old – a story that would inspire and support those fledgling traits, one that would open up the future, one that would show two clearly defined paths that could be taken – a path that leads to discovery and personal satisfaction, another that leads to avarice, meanness, power, influence and money.

Heady things for young impressionable minds.

Now imagine that one of those paths leads to godhood and the other to destruction.

Unfortunately for MY young and impressionable mind, the path that leads to power, influence and money is not the same one that leads to godhood.

Sturgeon’s story no doubt reinforced the nascent belief in my ten year old brain that discovery, exploration and self-satisfaction were far more important (and exciting) than any amount of money or power I might attain. It may also be responsible for my general belief that “money=bad” (though an earlier encounter with a busted piggybank and Batman collector cards – the TV series – does bear some responsibility). (Of course I know that its really “people with money often equals bad”, a contention that has been lent more credence following several new studies. But I digress.)

So what about this story? And what in the hell is a Microcosmic God?

Based on the events of the story, a microcosmic god is a god of a small cosmos. But lets do this right and start from the beginning.

Microcosmic God starts right off telling us exactly what the story is all about:

Here is a story about a man who had too much power, and a man who took too much, but don’t worry; I’m not going political on you. The man who had the power was named James Kidder and the other was his banker.

That’s a pretty straight forward opening and a soft but effective hook. It leads you to believe that the rest of the story is going to be about the conflict between Kidder and his banker. It also leads you to believe – by invoking the banker – that the power in question is of the conventional variety – money.

If you stop after that first sentence and ponder it, you might find yourself wondering if it is a story of embezzlement (Sturgeon has already shut down the subject of politics). Regardless, for a science fiction story, it certainly begins with some very pedestrian presentations. The denouement ends up all that much more forceful for this kind of opening; Sturgeon will take us along as he climbs the heights of human ambition steadily throughout the course of this tale.

I also find it interesting that the opening makes no bones about the fact that this is a story. No ms found in a bottle is cited, no subterfuge is used to fool us into a suspension of disbelief. Ted is going to tell us a story. Actually, he’s going to tell us a parable, a morality tale thinly disguised in the trappings of science fiction, a tale of hubris, triumph and defeat.

Now before we continue, a bit of the obvious. This story is very male centered. In fact, not a single woman appears anywhere in the narrative. I suppose that one can dismiss the story on that basis alone. On the other hand, this is a fable and the characters are not really meant to represent an individual person so much as they are there as stand-ins for a frame of reference. It is entirely possible to change pronouns – from he to she – and it won’t affect the story in any way at all. In fact, doing so might be a fun exercise.

The other thing that’s pretty obvious here is that technology has advanced greatly since the story’s publication – not only has it changed, scientific thought on one of the primary ideas introduced here – enforced evolution – has been eclipsed by genetic engineering. In that regard we’ll have to give Ted a pass. When written, Sturgeon’s SFnal idea was quite the concept. Now it sounds almost like the ravings of a mad scientist.

Which Kidder is. He’s a unique kind of mad scientist. His goal is not to take over the world but rather the opposite: Kidder wants to use his discoveries to keep the world at bay.

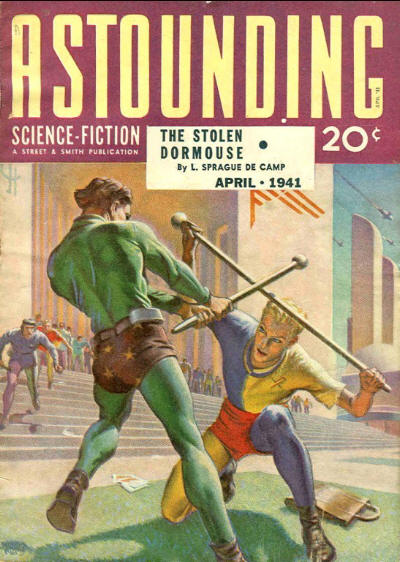

Before we continue, a bit about the times: when Microcosmic God was first published in the April, 1941 issue of Astounding Stories, The US entry into World War II was still eight months away; the Lend-Lease program was introduced in Congress; Puerto Ricans became US citizens; Plutonium was isolated and discovered; the National Art Gallery in DC was opened; CheeriOats (Cheerios) are sold for the first time; Bob Hope performs his first USO show; the worlds first ‘Turing complete’, programmable and automatic computer is unveiled in Germany; a patient is treated with Penicillin for the first time; the order to create an Atomic Bomb is issued by Roosevelt; a year before, the first ‘transposons’ were discovered in maize. (Transposons are gene sequences that can change location and may lead to mutation; perhaps speculation on this discovery lead, in part, to the genesis of this story).

Before we continue, a bit about the times: when Microcosmic God was first published in the April, 1941 issue of Astounding Stories, The US entry into World War II was still eight months away; the Lend-Lease program was introduced in Congress; Puerto Ricans became US citizens; Plutonium was isolated and discovered; the National Art Gallery in DC was opened; CheeriOats (Cheerios) are sold for the first time; Bob Hope performs his first USO show; the worlds first ‘Turing complete’, programmable and automatic computer is unveiled in Germany; a patient is treated with Penicillin for the first time; the order to create an Atomic Bomb is issued by Roosevelt; a year before, the first ‘transposons’ were discovered in maize. (Transposons are gene sequences that can change location and may lead to mutation; perhaps speculation on this discovery lead, in part, to the genesis of this story).

Kidder had created a few technological advances earlier, development of which provided him with enough income to purchase a private island – and to hiring a banker who would handle everything financial for him as Kidder demonstrably has no interest in such pedestrian matters. So long as he has enough money to keep himself in food and can purchase the resources that he needs to further his experiments, the rest of us can go hang.

Sturgeon’s description of Kidder is quite revealing:

Kidder was quite a guy. He was a scientist and he lived on a small island off the New England coast all by himself. He wasn’t the dwarfed little gnome of a mad scientist you read about. His hobby wasn’t personal profit, and he wasn’t a megalomaniac with a Russian name and no scruples. He wasn’t insidious, and he wasn’t even particularly subversive. He kept his hair cut and his nails clean and he lived and thought like a reasonable human being. He was slightly on the baby-faced side; he was inclined to be a hermit; he was short and plump and – brilliant. His speciality was biochemistry, and he was always called Mr. Kidder. Not “Dr.” Not “Professor.” Just Mr. Kidder.

Sturgeon goes on the explain that Kidder has no formal degrees and had a peculiar, straight-forward way of obtaining the information he needed:

If he was talking to someone who had knowledge, he went in there and got it, leaving his victim breathless. If he was talking to someone whose knowledge was already in his possession, he only asked repeatedly, “How do you know?” His most delectable pleasure was cutting a fanatical eugenicist into conversational ribbons. So people left him alone and never, never asked him to tea. He was polite, but not politic.

Sturgeon then relates that Kidder’s wealth was due to the development of a new fiber “That’s why ships now moor themselves with what looks like heaving line, no thicker than a lead pencil, that can be coiled on reels like a garden hose.” (Sturrgeon spent some time at sea….) and shortly thereafter, as Sturgeon catalogs Kidder’s discoveries, we learn just how little interest Kidder has with the rest of the world. Kidder stops ordering supplies and his banker, eager to keep the gravy train flowing, sends someone to investigate. They discover that Kidder is getting along fine with ‘dirtless farming’ he’s developed. The banker writes to Kidder –

…wanted to know if Mr. Kidder, in his own interests, was willing to release the secret…Kidder replied that he would be glad to…In a P.S. he said that he hadn’t sent the information ashore because he hadn’t realized anyone would be interested.

Sturgeon then recounts “a partial list of the things he turned out.” A way to make aluminum stronger than steel; a light absorber; synthetic chlorophyll, a super-sonic airplane propeller; a brush-on, pull-off paint remover; self-sustaining atomic reaction with U-235.

Kidder is quite the guy…or is he? Maybe he has a secret.

Which you’ll have to wait till our next installment to learn all about.

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.